Section Branding

Header Content

PHOTOS: South Africa's 'train of hope' is a godsend for millions. But new threats loom

Primary Content

It's late evening in the town of Thaba Nchu in South Africa's Free State province, and at the local train station, a group of residents snuggle deeper into their blankets to ward off the bitter autumn chill. They have given up warm beds and cooked meals at home in exchange for hard plastic chairs on the platform in their eagerness to get a spot on the train the following day.

Yet none of them is looking to travel.

The train they have come for is the Phelophepa, a 19-carriage mobile health-care clinic that has been crisscrossing South Africa since 1994. "Phelophepa" is a combination of the Sotho and Tswana languages meaning "good, clean health." Equipped with modern, well-maintained facilities, a fully stocked pharmacy and a team of 22 medical personnel, the Phelophepa offers a full range of primary health-care services to people in rural and under-resourced areas of the country who may otherwise have to go without.

Dubbed the "train of hope" by the late South African anti-apartheid activist Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the Phelophepa, operated and funded by the state-owned freight rail and ports company Transnet, has helped some 14 million South Africans over the past 28 years. In that time, it has weathered political upheavals, financial crises and the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, an unprecedented spree of looting and vandalism on the country's railways could pose its greatest challenge yet.

Making 'hay while the sun shines'

Among those waiting overnight at Thaba Nchu railway station is Doris Mokabi, who traveled over an hour from her home in the township of Botshabelo with only a thick blanket, a fold-up camping chair and a bag of multicolored popcorn to see her through the night.

"There are closer clinics but they're too expensive," says Mokabi, who has come here to see the Phelophepa's eye care department to address her deteriorating eyesight.

Others have come for dental care, HIV tests, psychological counseling or the treatment of infections. And some, like 62-year-old retired nurse Theophilius Links, simply aim to access as many of the train's services as possible before it leaves town.

"You have to make hay while the sun shines," says Links, who intends to get a cancer screening, an eye test, a general health check and his second COVID-19 vaccine booster, among other health services.

How the health-care train works

Stopping for two weeks at a time in around 20 small towns across the country — selected mainly for their lack of access to health care — the train operates for nine months of the year. Along with its permanent medical staff, it is home to around 40 medical students on temporary work placements from universities all over South Africa, as well as about 15 support personnel who deal with security, logistics and catering. The staff live onboard in tiny compartments or dormitories and get occasional leave.

Both Mokabi and Links say they prefer the Phelophepa train to their local clinics, not least because they know they can access services either free of charge or for just a nominal fee. Operated as a charity project, the train's services are heavily subsidized by the Transnet Foundation.

"I've come here because it's affordable and it's a very high standard of care," says Links. "In the clinics [in this area], there aren't enough doctors and nurses."

Private health care in South Africa is prohibitively expensive for most, while the public health service is hampered by a shortage of staff and facilities, especially in rural areas. Just up the hill from Thaba Nchu railway station, the local Gaongalelwe Health Clinic does its best to serve a population of 26,000 people — despite not having a single doctor on staff. Instead, the clinic relies on occasional visits from doctors based in other nearby health facilities.

"It's too much for one clinic," says Gaongalelwe manager Yolande Safers. "We're only five nurses."

South Africa is not alone in using medical trains to reach patients in need. In India, the Lifeline Express has been bolstering rural health care since 1991, while in Russia, a handful of hospital trains have been enlisted to serve remote parts of Siberia. More recently, the Ukrainian government has begun using a hospital train to treat and evacuate patients who have been wounded in the Russian invasion.

Stop-and-go care

For Ntombi Pukwana, manager of the Phelophepa's psychology clinic, seeing the level of need in the community is a reminder of the train's critical role. But she says it can also be frustrating to know that once she and her team have moved on, few of her patients will be able to access the long-term care they need in the local area.

"In about half of the towns we stop at there's a psychologist" says Pukwana. "The rest of the time there's nobody at all. Sometimes there's no psychologist for 200 miles."

The same is true of other departments on the health-care train. Data collected by Transnet in 2016 showed that only a small fraction of patients referred for cataract removal by the Phelophepa's eye clinic the previous year had been able to get surgery, mainly due to a large backlog at government hospitals. In response, Transnet has been considering launching a surgery train fitted with onboard operating theaters, something the Phelophepa lacks.

Trouble on the train tracks

Running a health center on a train poses daunting logistical challenges at the best of times, but the last two years have been tougher than most. First, the Phelophepa was called on to support the national fight against COVID-19. Since the start of the pandemic, it has carried out 210,000 tests and administered more than 28,000 doses of vaccine alongside its normal work.

But the greatest challenge, says Dr. Bheki Mendlula, an optometrist and the train's manager, is the ongoing looting of South Africa's railway infrastructure by opportunists looking to make a quick profit from selling scrap metal. This has disrupted the Phelophepa's operations and cost Transnet almost $250 million, threatening the company's ability to continue funding the project in the long term, Mendlula says.

"Things don't go as planned. There are delays due to locomotives breaking down along the route, or you might have theft of cables or rail tracks tampered with," says Mendlula.

During the pandemic, the problem escalated from an occasional hindrance to a full-blown epidemic that has seen some train lines grind to a halt completely. Thieves have stripped the electric cables from huge stretches of track in order to extract the valuable copper wire within. Others have targeted the rail tracks themselves, or the batteries that provide power for signaling equipment. In Thaba Nchu, the station platform is being gradually removed, brick by brick. And one Phelophepa security guard said he frequently had to prevent thieves from stealing parts of the train itself.

"It puts our lives at risk and it sets us against the community we're trying to serve," says Mendlula, explaining that the disruption often reduces the amount of time the train is able to stay in a community. This in turn leads to friction, he adds, when there is not enough time to see all the would-be patients. "If the community has been informed that next week you'll be here, and you don't come, then it means that a lot of people won't get services."

During the journey to Thaba Nchu, a short hop from the train's previous stop in the nearby town of Kroonstad, the Phelophepa had once again been blocked by dangling cables on the track. On this occasion, a maintenance team had been quick to respond, and after an hour's delay the train was once again underway.

But the Phelophepa is nothing if not resilient. And for Mendlula and his team, there is a sense of both pride and responsibility in overcoming these obstacles to continue providing services to South Africans in need.

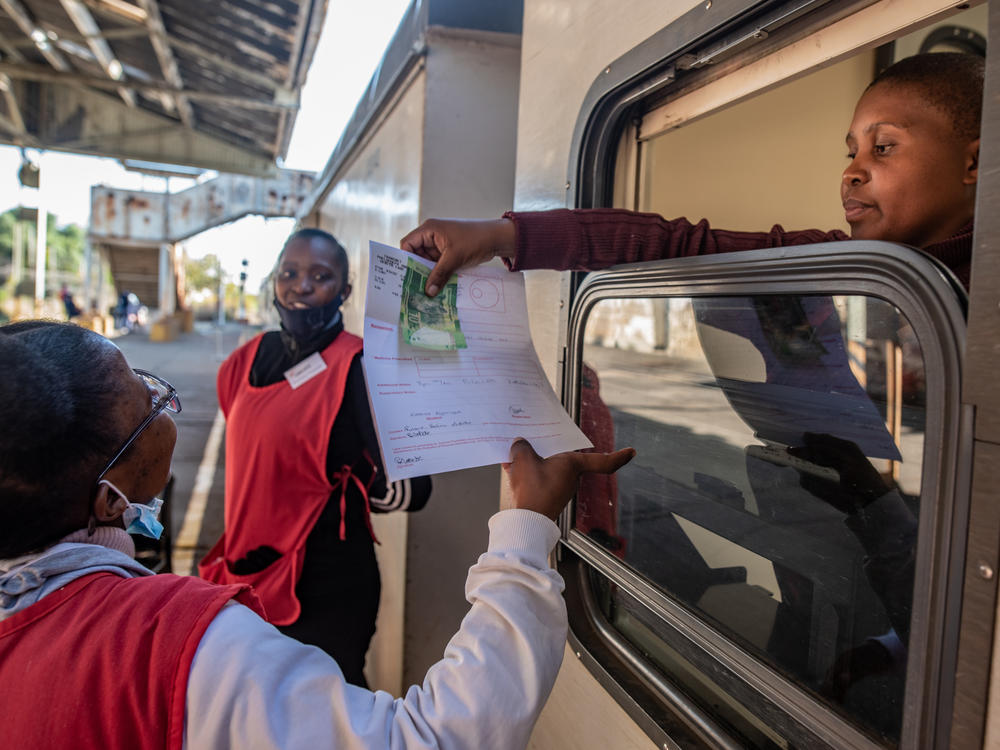

"The demand out there is just massive," he says, as the last of the day's patients wait to pick up their prescriptions from the pharmacy. "People call this the miracle train. It's a privilege to be a part of it."

Tommy Trenchard is an independent photojournalist based in Cape Town, South Africa. He has previously contributed photos and stories to NPR on the Mozambique cyclone of 2019, the Ebola outbreak and Indonesian death rituals.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.