Section Branding

Header Content

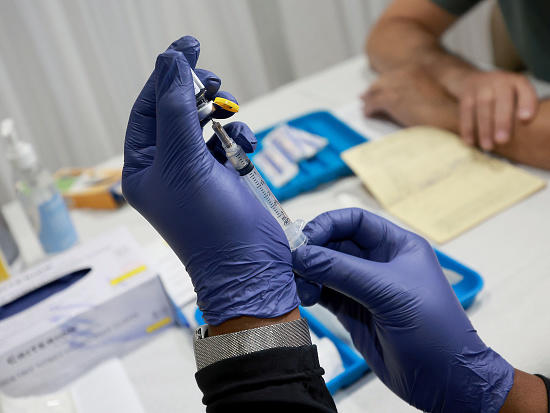

There's a bit of good news about monkeypox. Is it because of the vaccine?

Primary Content

Finally, we have a glimmer of good news about monkeypox: The outbreaks in some countries, including the U.K., Germany and parts of Canada, are starting to slow down.

On top of that, the outbreak in New York City may also be peaking and on the decline, according to new data from the city's health department.

All these outbreaks are "far from extinguished," says infectious disease specialist Dr. Donald Vinh at McGill University in Montreal. But there are signs that, in some places, "they're a bit more under control than they had been."

For example, in the U.K., the number of new cases reported each day has steadily declined since late July, dropping from 50 daily cases to only about 25. (By contrast, here in the U.S., daily cases are still increasing. Since late July, the U.S. daily count has risen from 350 new cases to 450 cases.)

Some health officials credit the monkeypox vaccine – and its quick rollout – as the key factor that's slowing the spread of the virus in the U.K..

"Over 25,000 have been vaccinated with the smallpox vaccine, as part of the strategy to contain the monkeypox outbreak in the UK.," the U.K. Health Security Agency wrote on Twitter on Tuesday. "These 1000s of vaccines, given by the NHS to those at highest risk of exposure, should have a significant impact on the transmission of the virus."

Indeed, the U.K. and parts of Canada rolled out the vaccine in late May, weeks before doses became available in most U.S. cities.

But does the monkeypox vaccine have the ability to stop or curb the spread of the virus? To answer that question, we need to first understand a few basics about this vaccine.

What actually is the monkeypox vaccine? How does it work?

So the monkeypox vaccine is actually the smallpox vaccine. Maybe that sounds a bit strange, but in fact the two pox viruses are related. They're a bit like cousins.

Health-care workers used an earlier version of this vaccine to eradicate smallpox in the 1970s. So versions of this vaccine have been given to hundreds of millions of people over the past century. It has a long track record.

Back in the late 1980s, researchers started to notice something remarkable about this vaccine. During a monkeypox outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then called Zaire), people who were immunized against smallpox were less likely to get monkeypox. They were protected. And not by just a little but by quite a bit. In a small study, published in 1988, researchers estimated the smallpox vaccine offered about 85% protection against monkeypox.

Now, the virus in this study was a different variant of monkeypox than the one circulating in the current international outbreak and that variant wasn't spreading primarily through sexual contact, as monkeypox is doing today. So we don't know how well these findings will translate to protection during the current outbreak. Which brings us to the next question.

How well does the vaccine protect against a monkeypox infection?

The short answer is: "We don't know," says infectious disease specialist Dr. Boghuma Titanji at Emory University.

There's no doubt the vaccine will offer some protection, Titanji says. "But right now, we still need studies in people to understand what level that protection actually is."

In North America and Europe, countries are primarily rolling out a vaccine called JYNNEOS, which was developed in the early 21st century. The goal with this vaccine is to increase its safety compared to the older vaccine, whose life-threatening complications, including encephalitis and skin necrosis, occurred in about 4 out of every million people vaccinated. That vaccine also could cause damaging skin lesions in people with eczema or weakened immune systems. (Note: There is a shortage of the JYNNEOS vaccine, and no doses have been shared with or sold to countries in Africa, which have experienced monkeypox outbreaks since the 1970s.)

Although older versions of the vaccine have been tested thoroughly in people, there has never been a large, clinical study to measure JYNNEOS's ability to protect against a monkeypox infection in people – or to stop transmission of the virus.

What is known about the vaccine, in terms of its efficacy against monkeypox, comes from studies in macaques, and immunological studies in people, which demonstrated the vaccine triggers the production of monkeypox antibodies in people's blood.

"So we know that the vaccine does stimulate the immune system and people produce antibodies when they receive the vaccine," Titanji says, "but we don't have a clinical data in humans to actually tell us, 'Okay, that immune response translates to this level of protection against getting infected with monkeypox or reducing the severity of monkeypox disease if you do get infected.' "

And it's not a guarantee of protection. In this current outbreak, scientists have already begun to document breakthrough infection with this vaccine, the World Health Organization reported Thursday. "[This] is also really important information because it tells us that the vaccine is not 100% effective in any given circumstance," said Dr. Rosamund Lewis of WHO. "We cannot expect 100% effectiveness at the moment based on this emerging information."

And so when Titanji gives a person the JYNNEOS vaccine at her clinic, she is very clear about what the vaccine can and can't do. "I tell them, 'We do know that you're going to get some protection from this vaccine. Some protection is better than no protection. We also do know that the vaccine can reduce the severity of the disease if you do get infected. But we don't know for a fact that you would be completely protected from getting monkeypox.' "

Can this vaccine – if given to the people who need it the most – slow down the outbreak?

So the new data from the U.K. and Germany suggest that indeed this vaccine can curb the spread of monkeypox.

But Dr. Vinh at McGill University says it's way too soon to say the vaccine, alone, is the only factor contributing to the slow down in these countries. "No single measure is going to really be the solution here," says Vinh.

In addition to vaccination, people at high risk need to learn how they can protect themselves. And doctors have to learn how to spot monkeypox cases, he says.

Right now the percentage of monkeypox tests coming back positive is still incredibly high, Titanji says. "The positivity rate is close to 40%." And that means doctors are missing many cases. Specifically, they are still mistaking monkeypox for other sexually transmitted diseases such as syphyllis.

"I can tell you, from the lens of a clinician, that monkeypox is very, very easy to mistake for another infectious disease," she says.

Some people have had to visit clinics two or three times – and even have been treated for another STD – before the clinician suspects monkeypox.

"You really have to maintain a very high index of suspicion because some of the lesions are so subtle and the clinical presentation is so variable," she says. "At this phase of the outbreak, we should be over testing rather than under testing. If a doctor even remotely suspects monkeypox, they should be sending a test for it."

Otherwise people can't receive treatment for monkeypox and they can unknowingly spread it to others. And the outbreak will continue to grow while people wait to receive a vaccine – and for that vaccine to begin working.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.