Section Branding

Header Content

The diary of an Afghan girl killed in bombing reveals a list of unfulfilled dreams

Primary Content

In an undated entry in her diary, 16-year-old Marzia Mohammadi drew up a list of all the things she wanted to do in her life. At the very top was her wish to meet the best-selling Turkish-British novelist Elif Shafak, followed by a visit to the Eiffel Tower in Paris and having pizza at an Italian restaurant.

Like Shafak, Marzia wanted to write a novel someday.

But Marzia's dreams came to crashing end on Friday, after she was killed in a suicide bombing attack on the Kaaj learning center in Kabul's predominantly Hazara ethnic neighborhood. Her cousin and best friend, Hajar Mohammadi, 16, was also among the 53 deaths, the majority of whom were girls, according to a U.N. agency.

Marzia's list included everyday things like wanting to ride a bike, learn the guitar, or walk in the park late at night — simple tasks women and girls could not aspire to while living under Taliban rule in Afghanistan.

But Marzia was different, said her uncle, Zaher Modaqeq, who found her diaries with her belongings after her death. "She was creative and had such clarity of thought. Some of her thoughts were so profound that I couldn't believe [they] were expressed by such a young child," he said, the grief evident in his voice.

The murders have evoked widespread condemnations and calls for justice globally, including from Marzia and Hajar's idol, Shafak. "It broke my heart to learn how they loved reading literature and how they loved reading my novels. The tragic death of Marzia and Hajar alongside dozens of other Hazara Afghan girls in a horrific suicide bombing at a learning centre in Kabul is utterly heart-wrenching," Shafak told NPR in an email.

"These girls were targeted and attacked both because they were female and because they were from a persecuted minority [Hazaras]. They have been systematically discriminated against and denied their most basic human rights," she said.

A rise in attacks

Attacks against Hazaras — largely Shia Muslims who have been historically persecuted by Sunni militant groups — have increased significantly in the past year since the Taliban takeover. A report published last month by the advocacy group Human Rights Watch documented 16 attacks against Hazaras that killed or injured at least 700 people.

"An important aspect of the ongoing targeted attacks against the Hazaras that is consistently overlooked is the disproportionate impact on women," said Anis Rezaei, a Hazara academic who is currently pursuing a master's degree at Oxford University.

"They bear a double burden ... Hazara women are not only discriminated against and often killed because of their gender identity, but also because of their Hazara identity," she said.

Predictably, since the Taliban has taken over, it has imposed many restrictions on women's freedoms, including the closure of girls' high schools. Millions of young Afghan girls, including Marzia's siblings, have been out of school for over a year.

However, the adversity of the situation only served to fuel Marzia and Hajar's motivation, Modaqeq said. "She [Marzia] was average student in high school, but following the Taliban takeover she was determined more than ever to complete her education and achieve goals," he said.

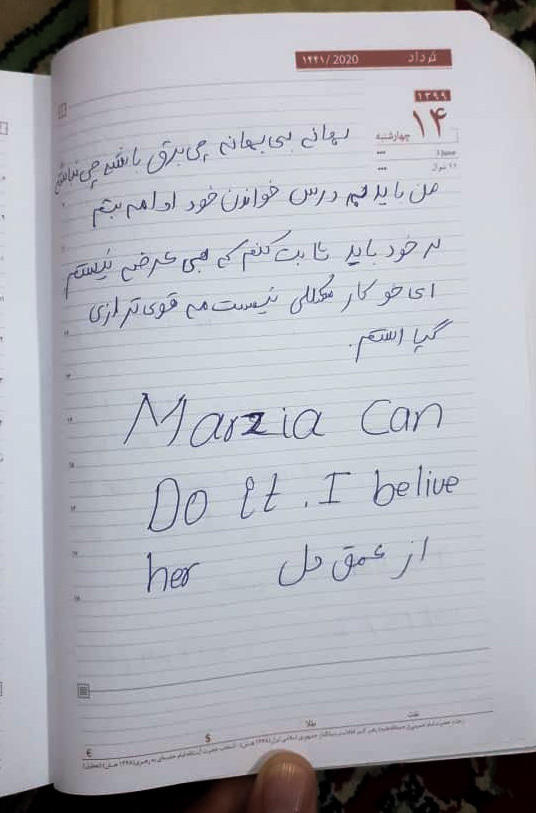

Modaqeq shared with NPR some of the pages of Marzia's diary, where she meticulously details her aspirations, sets goals for herself, discusses the struggles she endures, and every once in a while, takes a moment to congratulate her achievements. Her notes provide a window into the lives and struggles of young Afghan girls, particularly Hazaras, living under the Taliban.

In an entry on August 15, 2021 — the day the Taliban seized Afghanistan's capital city — Marzia writes, "People are scared. We are in shock and disbelief over the situation, especially for girls like me," referring to the Taliban's restrictions on women's freedoms and rights.

As the American troops tried to secure Kabul that night, Marzia and Hajar distracted themselves from the chaos around them by watching the American movie I Still Believe. Before going to bed that night, Marzia wrote in her diary, "An entire day wasted."

On August 23, she described her first experience of the city under Taliban rule: "Stepped out for the first time since the arrival of the Taliban. It was scary and I felt very insecure. I purchased Elif Shafak's Architect's Apprentice, and today I realised how much I love books and libraries. I like seeing the joy on people's faces reading books."

And the next day, she wrote, "I had a tiring day ... I had some nightmares, I can't remember but I was crying in my sleep and I was screaming. When I woke up, I had an uncomfortable feeling. I went to a corner and cried and felt better."

"Through her diaries we learned that she and Hajar wanted to be architects, which involves their love for art and creativity," Modaqeq said, adding that the girls had thoroughly researched the courses and the industry and had been taking weekly practice tests at the learning center.

Marzia and Hajar scored 50 and 51 percent out of 100 respectively on the first practice test they took. In the diary entry that day, Marzia remarked that she was not happy with the score and she would aim to get 60 on the next week's mock test. She scored 61. On that day, she wrote, "Wow, Bravo Marzia!"

She would set goals for herself and for Hajar, and both girls were motivated to work hard and achieve them, her uncle said. In one of the entries, Marzia writes: "No excuses, with or without electricity, I have to continue my studies. I have to prove to myself that I am stronger." Below that, Marzia scrawled in English: "Marzia can do it. I believe her from the bottom of my heart."

Her uncle said her scores gradually improved. "Her last score was at 82 percent. She had hoped to maintain the score this week, but then ...," her uncle said, unable to finish his thought.

Hazaras repeatedly targeted

"This is not an isolated incident," Rezaei said. The latest bombing was the fourth attack targeting Hazara schools in Kabul since 2018, claiming over 200 young lives. The Kaaj learning center, where Marzia and Hajar were killed, was also targeted in 2018, when it was called Mawoud Academy, in an attack that killed 40 people and injured 67.

"It represents a pattern of systematic targeted attacks on the Hazara people. Over the past 20 years, Hazaras have been the victims of genocidal attacks in their schools, sports clubs, hospitals, wedding ceremonies and other social gatherings," Rezaei said, pointing out that none of the perpetrators of these attacks have been brought to justice under any government.

Modaqeq agrees, adding that Hazara students were repeatedly targeted for their love of learning. "The terrorists often target Hazara places of education, because Hazaras have cultivated this love for learning and growing through education," Modaqeq said.

"It wasn't easy, and less than three decades ago, many Hazara parents would be reluctant to send their girls to school, but that changed gradually through awakening social consciousness within the community," he said.

Modaqeq hopes to see a similar awakening in the wider Afghan society. "I may sound very idealistic but I truly believe that the only way for the violence to end in Afghanistan is through education," he said.

Shafak also shared a message of solidarity with girls of Afghanistan. "I have enormous respect for the women and girls in Afghanistan who are fighting for their right to education. I am in awe of their bravery," she said, adding a personal note: "You are not alone."

Ruchi Kumar is a journalist who reports on conflict, politics, development and culture in India and Afghanistan. She tweets at @RuchiKumar

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.