Section Branding

Header Content

Death and dishonesty: Stories of two workers who built the World Cup stadiums in Qatar

Primary Content

Updated December 2, 2022 at 10:21 AM ET

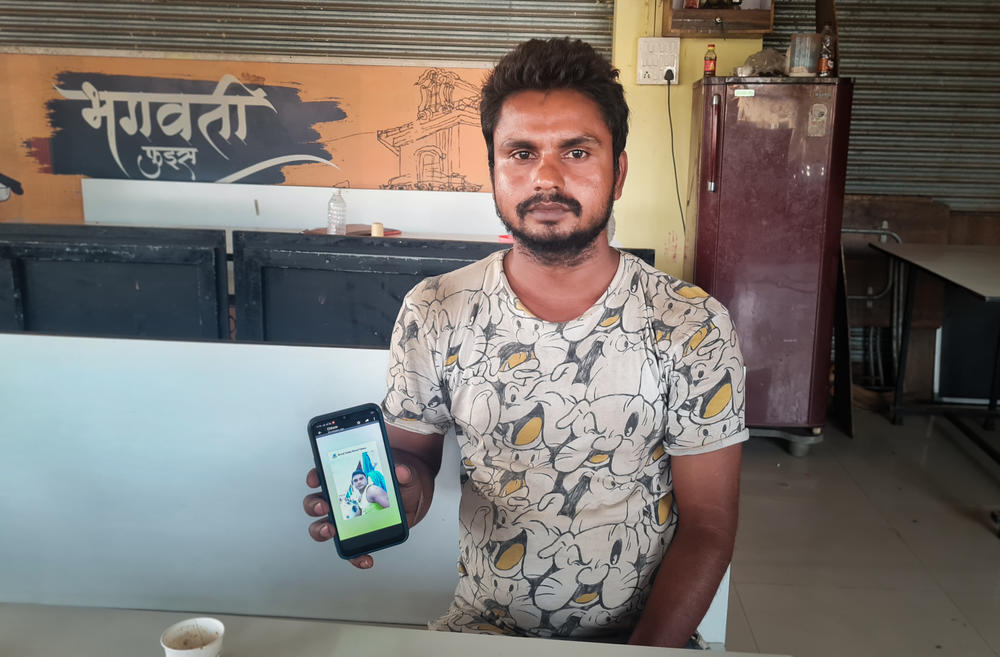

MUMBAI, India – At dusk, as neighborhood children toss a ball around in park lined with palm trees on the outskirts of Mumbai, Ashwini Kumar looks on from a bench nearby.

Watching them shout and cheer about their favorite soccer superstars – Ronaldo! Messi! – is painful for him. It reminds him of his big brother.

"We used to play soccer together almost every evening when we were kids, in a park just like this one," Kumar, 24, recalls. "We played and played until it was so dark you couldn't see the ball!"

As they grew up, Vinod's love of soccer grew. He even won some local tournaments. So he was thrilled, his brother recalls, when he got a job three years ago to work in Qatar, building stadiums that would one day host the 2022 World Cup.

But Vinod never came home. He's one of what Qatari authorities say is hundreds — and human rights investigators say is thousands — of World Cup workers who died there.

There's been a lot of controversy over how the tiny Gulf nation of Qatar is hosting the biggest sports event in the world, the World Cup. Some of it has centered on labor conditions. Like much of the Gulf, Qatar's economy relies heavily on migrant labor. (By some estimates, migrant workers make up 90% of the country's work force.)

Many of them are from South Asia, and they've returned home with stories of poor working conditions, cramped accommodation, broken promises about pay – and back-breaking work in 125-degree heat.

For them, the World Cup brings mixed feelings. Many are proud to have helped build Qatar's infrastructure. For others, the hype around the tournament only brings back trauma.

A series of calls from Qatar — but no clear explanation of a family member's death

The Kumar family never really got answers.

"I got a call from his colleagues. They used my nickname – chhote, the young one. It's something only my family would call me," Ashwini Kumar recalls that fateful phone call in Oct. 2020. "They said my brother was missing and hung up. Then they called back and told me he was dead."

Kumar says the family got various calls from coworkers and supervisors, who gave different explanations for Vinod's death: That he died by suicide. Or in a workplace accident. Ashwini does remember his brother saying he was forced to do tasks he wasn't trained for, like firefighting.

"He was sent there as a plumber but was made to do other work as well — like working as a fireman in tall buildings, and risky construction work where he had to climb on a pipe," he says. "Once we did a video call while he was working as a painter. And later he worked as a cleaner."

The company that hired him never sent home his stuff. Vinod Kumar was 28. He leaves behind a widow and a toddler. They're struggling financially and have moved in with Kumar's parents.

"The world should remember this, while watching our favorite teams in these air-conditioned stadiums," says Namrata Raju, an economist and labor researcher with Equidem, a global labor rights group that conducted an 18-month investigation into working conditions for migrant workers in Qatar, in the lead-up to this World Cup.

Raju says she and her colleagues interviewed nearly 1,000 migrant laborers.

"They alleged really worrying things: Nationality-based discrimination, wage theft was very common — and there were a lot of cases of overwork," she says. "Essentially, the conditions we found workers in were varying forms of forced labor or other forms of modern slavery. That's what we found."

The World Cup has brought scrutiny to the issue of migrant labor in the Gulf, which has concerned human rights advocates since well before Qatar won its bid, in 2010, to host this year's tournament.

Qatar defends itself

Qatar says it's faced unfair scrutiny and that its labor conditions have actually improved because of the World Cup.

"What the World Cup did was it allowed for a significant number of reforms to be accelerated," said the Qatari official in charge of World Cup infrastructure, Hassan Al Thawadi, at a think tank conference in October. "We always had laws and legislations that were in line with international standards. Yet the enforcement mechanisms — the oversight — was not to the standards that we were proud of."

"We recognized early on that the World Cup would create momentum that will push a lot of that reform," he said.

In 2017, Qatar overhauled its migrant labor laws. It added protections for live-in domestic workers and labor tribunals. Last year, it became the first country in the Gulf to introduce a minimum wage that applies to all workers, regardless of nationality.

Amnesty International says there have been "noticeable improvements" in labor rights in Qatar over the past five years. But "a lack of effective implementation and enforcement" still persists, the group says.

Migrant workers returning from Qatar say the same.

A Nepali migrant worker says he was misled about working conditions in Qatar

During his 33 months working construction in Qatar, Anish Adhikari never managed to get out of debt.

By phone from his native Nepal, he told NPR how he had to take out a loan to pay a nearly $900 recruitment fee to a Nepali agent, just to get a job in Qatar in the first place — with the Hamad Bin Khalid Contracting Company,or HBK — which is named after and owned by Qatar's royal family.

Officials from HBK did conduct safety inspections, Adhikari recalls. But he says his site supervisors rushed workers out of the half-built stadium ahead of the visits so that it wouldn't be as overcrowded. He blames contractors and sub-contractors for shoddy implementation of labor laws in Qatar – and the Qatari government for not policing its contractors.

He also believes that potential workers did not get an accurate picture of what to expect. "The recruitment company knows everything about the condition of migrant workers in Qatar. But they lie. They focus only focus on profits for themselves," Adhikari says. "They sell a dream that's not reality."

It took Adhikari nearly six months to earn back his recruitment fee, at his salary of about $165 dollars a month – about two-thirds of what he was promised. It was still more money than he could earn in Nepal though, he acknowledges.

But the conditions, he says, were back-breaking. "In Nepal, at least you're allowed to rest! In Qatar, they threatened to cut my salary if I took breaks," Adhikari says. "And the weather was up to 52 degrees [124F], so it was very difficult. It wasn't worth it for me."

Now he's back in the Nepali capital Kathmandu, looking for work.

Despite the hardships on the job, Adhikari says he is still proud that he helped build the shimmering gold Lusail Stadium, which will host the World Cup final on Dec. 18.

Will he watch that game?

He'd like to find a way, he says, but he's unsure. "I don't have a TV. I have to watch on my cell phone, but I don't have good wifi – and data is expensive," Adhikari explains. Money is tight even with his Qatar earnings. His family is still in debt.

Ashwini Kumar, who lost his brother, won't be watching either.

It was his brother Vinod who loved soccer, he says. And he died for it.

NPR producer Raksha Kumar contributed to this story from Mumbai, and freelance interpreter Shreemanjari Tamraka contributed from Kathmandu.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.