Section Branding

Header Content

This graphic novel imagines what would happen if you could buy and sell wishes

Primary Content

If Egyptian comics artist and writer Deena Mohamed ever encountered a genie, she knows what she'd wish for. She'd wish for everyone she loved to live to age 120. And she'd wish for any book she ever wanted to read to appear right in front of her eyes.

"If I ever come across a genie, I have to be ready," she says. "They have to be smart wishes."

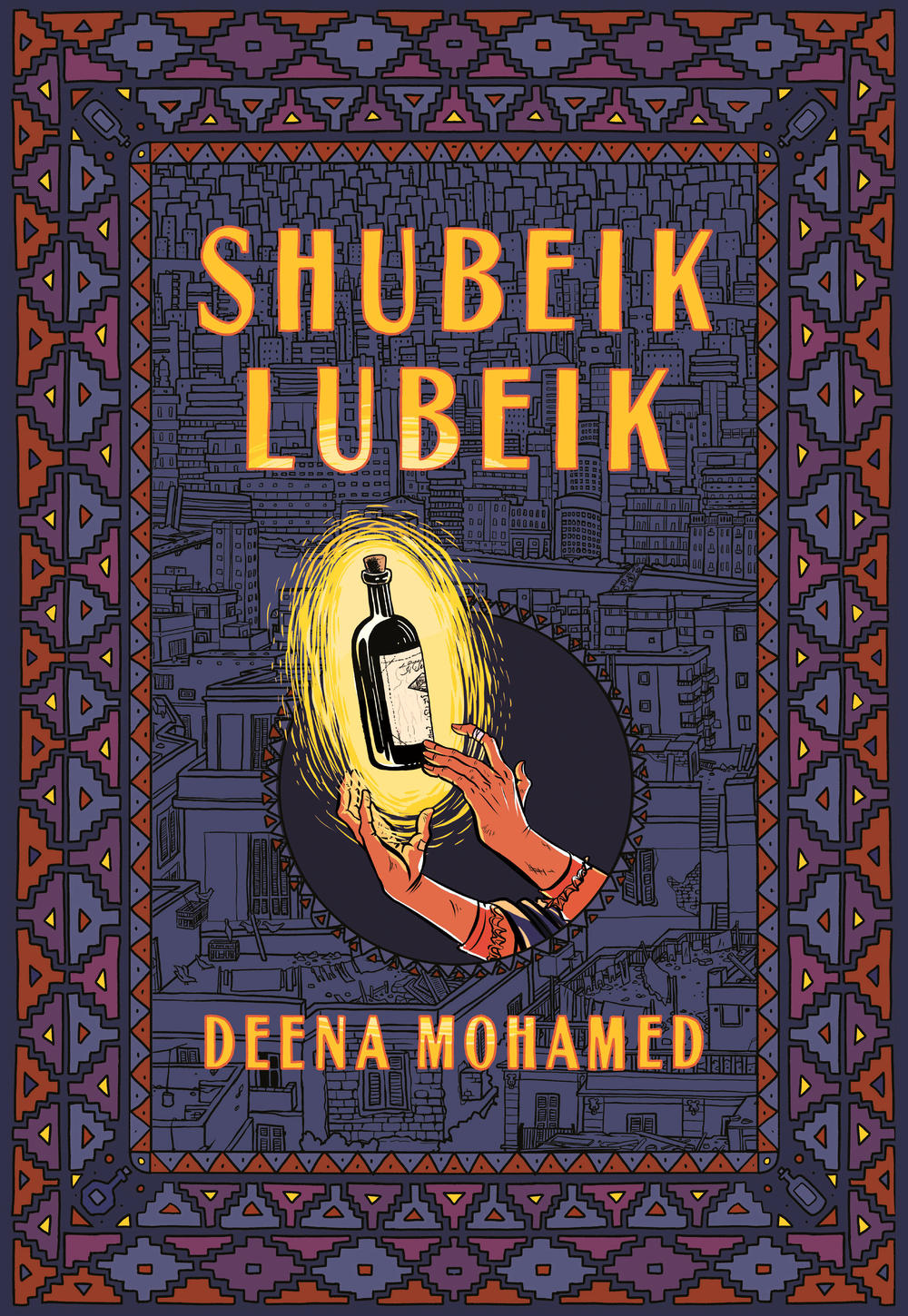

Wishes are the theme of her debut graphic fantasy novel, Shubeik Lubeik, Arabic for "your wish is my command," published this week by Pantheon Books. The book follows Shokry, a kiosk owner in Cairo, Egypt, as he tries to sell off three wishes he inherited from his father. A pious Muslim, he refuses to use the wishes on himself because he worries they might not be in the spirit of Islam — but meets three Egyptians whose lives can be radically transformed by the power of a wish.

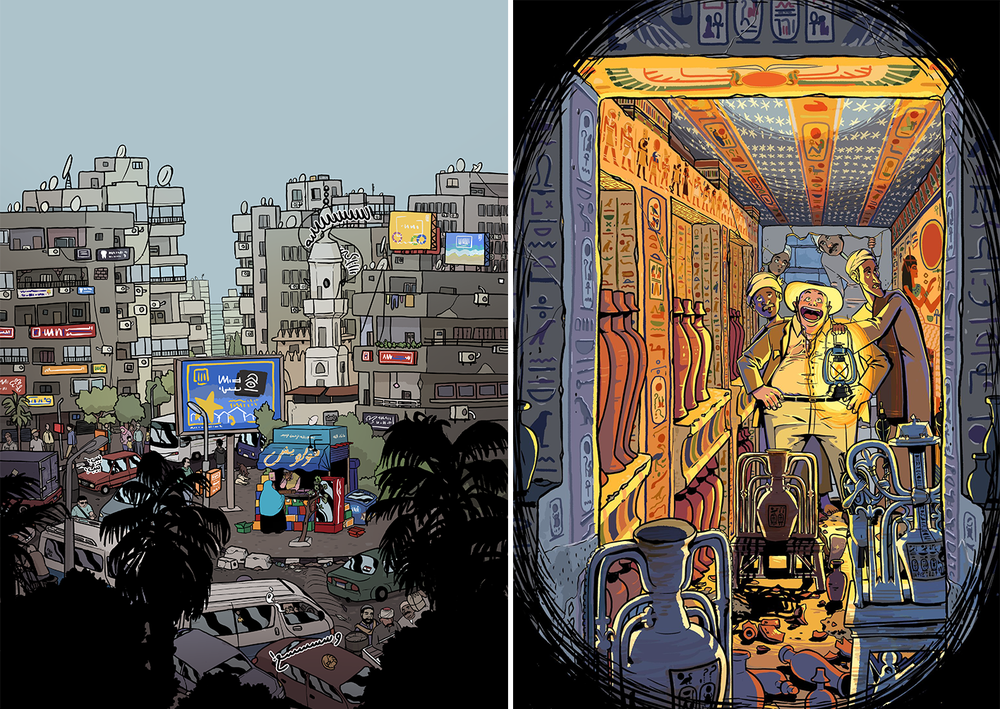

The book highlights the fantastical — there are dragons, talking donkeys and a hilarious scene where someone wishes for a BMW and gets a toy car. But the story is also remarkably grounded in the realities of modern life in Egypt, a country where nearly 70% of citizens live on less than $5.50 a day. Along with authentic illustrations of Cairo's locals and cityscape, the book has characters who grapple with poverty, economic inequality, a poor health-care system and preventable disease.

The book also confronts the bureaucracy of living in a low-resource nation, where the poor must navigate labyrinthine processes to get what they need. One character, an impoverished woman named Aziza, picks up trash, scrubs floors and works menial jobs to buy a wish – only to find that before she can use it, she must register her wish with Egypt's Ministry of Wishes. When she finally gets in front of a government worker, they assume she has stolen the wish and confiscate it. Mohamed writes, "What stands between you and your wish could be a government employee with paperwork on the fourth floor."

Mohamed, 28, who was born and raised in Cairo, didn't know how to tell the story in any other way. "It's just the way I've experienced the world. So it's the way I built my own world."

The book was originally self-published as a trilogy in Arabic from 2017 to 2021. In 2017, the trilogy won the top prize at the Cairo Comix Festival, an annual comics convention for cartoonists in Egypt and the Middle East. She's excited to see how an English-speaking audience will react to her creation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You started working on Shubeik Lubeik when you were just 21 years old. What inspired you to make this comic with such a fantasy plot — a kiosk that sells wishes?

I knew I wanted to build a story around the Egyptian kiosks, the kind you would see on the street.

These kiosks in Egypt are everywhere. They're where people can buy a bottle of Coke, cigarettes, the newspaper, a phone card, a bag of chips or a popsicle.

I like how they look and how each one is unique because it's customized by the person who builds it. And I knew for my story I wanted one to sell a magical object. At first I wasn't sure what that magical object should be. But once I decided on a wish, I started to build my story around it. What kind of world would have to exist for someone to be able to buy a wish from a kiosk?

Even though it's a fantasy world, it's definitely similar to our real world.

When I was thinking about wishes sold at a kiosk, I constructed the idea of [low-quality] cheap wishes, called "third-class" wishes, and [high-quality] expensive wishes, called "first-class" wishes. So if there is a sort of commodification happening, there is immediately an issue of access. If you're poor, the [high-quality] wishes will be out of reach. But if you're rich, you will be able to afford mountains of wishes.

And like many precious resources found in low-resource nations, rich countries find a way to exploit wishes. In your book, British explorers discover a trove of wishes in a tomb and begin "extracting" them and splitting them into first-, second- and third-class wishes, of which are sold for profit. Are wishes a symbol for something we might encounter in the real world?

I didn't want it to be like a metaphor for something directly. I did, however, use several models for how wishes would be controlled [in the real world]. Whenever I felt a little lost for how something like wishes could exist, I realized that it's similar to money. It can make things possible if you have access to it. And the way that wishes are extracted and regulated is similar to oil.

In the book we meet several characters who need wishes, like Shawqia, an older Christian woman who is diagnosed with cancer but has a hard time finding medical treatment in Egypt. Is she based on anyone in real life?

No one is based on a real person, but I might base some aspects of the characters on different situations I've experienced. For example, I had an aunt who had cancer and she had trouble finding a bed [at a hospital] even though she could afford one. There wasn't anyone willing to admit her because she was so sick. So there was this race across Cairo to try to find all the different hospitals she could go to.

In another scene, Shawqia begs her husband to let her use her wish to save their two children, who are dying of hepatitis. They had contracted the disease via an infected needle for treatment for schistosomiasis, a disease caused by parasitic worms.

Schistosomiasis has been a widespread problem since the Pharaonic times. Everyone in Egypt knows the dangers of swimming in the Nile [where the parasitic flatworms lurk and spread disease]. It was so common for people to have blood in their urine [a symptom of schistosomiasis] that they thought men could menstruate.

Because of schistosomiasis, [Egyptian health officials and the World Health Organization] had a campaign to treat the disease [from the 1950s to the 1980s]. They administered a course of shots with glass syringes, which were then reused. And that resulted in a very bad hepatitis epidemic in Egypt.

What was the significance of telling that story in Shubeik Lubeik?

The theme of Shawqia's section was health and I wanted her story to feel grounded in what was happening in Egypt at that time. And schistosomiasis was a real struggle that actually affected people.

You were very intentional about drawing your book in the style of traditional Egyptian comics. What does that look like?

Egyptian cartooning is influenced by political satire, so it has a style of cartooning that exaggerates features. It isn't concerned with making people look beautiful. It's more about facial expressions. You cannot be shy to draw people with ugly features.

Why was it important for you to draw in this style?

I wanted the book to be something that Egyptians would be comfortable with, so it had to have a visual identity that felt Egyptian.

The concept of wishes is distinctly Middle Eastern — many people learn about them from the story of Aladdin in the fairy tale collection Alf Leila w Leila, or One Thousand and One Nights. And even though your book is very modern, it follows the morals of that classic book.

I conceptualized wishes the way other people might conceptualize prayer. You pray when you want something the most. This would be done most likely in the event of regret, if you lose something, or when you really want something. There's a theme for each wish in the book: grief, happiness and health. These are very universal themes, things that people wish and pray for the most.

Malaka Gharib is a comics artist and the author of two graphic memoirs, I Was Their American Dream, about her Egyptian Filipino American identity, and It Won't Always Be Like This, about her summers in Egypt.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.