Section Branding

Header Content

Why inventing a vaccine for AIDS is tougher than for COVID

Primary Content

The four-decades long effort to create an HIV vaccine suffered a blow last week with news that Janssen Pharmaceuticals, a division of Johnson & Johnson, was discontinuing the only current late-stage clinical trial of a vaccine. Results showed it to be ineffective.

"I was disappointed in the outcome," says Mitchell Warren, executive director of AVAC, an organization that advocates for HIV prevention to end AIDS. "It was a setback in the search for a vaccine." So it's back to the drawing board with several early, small-scale clinical trials underway and more that might eventually enter the research pipeline.

Since 1982, when the U.S. Centers for Disease Control first named the syndrome "AIDS," there have been years of fear and death that gave way to startling scientific advancements in understanding and treating AIDS.

But the holy grail has always been to find a vaccine that would prevent people from being infected with HIV.

"The only way we've ever actually eradicated a disease [in humans], and that was smallpox, is with a vaccine," says Dr. Susan Buchbinder, director of HIV prevention research at the San Francisco Department of Public Health and a professor at the University of California, San Francisco.

Medical advances in AIDS include antiretroviral medications (ART) to suppress the virus and keep the disease under control; and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) drugs to prevent HIV transmission if taken correctly by uninfected people who see themselves at risk. Today almost 29 million of the world's 38 million HIV-infected people have access to life-saving ART drugs, according to UNAIDS.

But access to PrEP medications has been much slower, and in 2020, 97% of the 940,000 worldwide PrEP users lived in just 30 countries, according to the World Health Organization.

And a vaccine against HIV remains frustratingly out of reach. That's in contrast to the under one year it took to develop vaccines against COVID-19 that prevent severe disease, hospitalization and death in most cases.

So, if scientists can do it so quickly for COVID-19, why can't they come up with a vaccine to prevent HIV?

A big part of the reason, says Warren, is the rate at which the AIDS virus mutates. "The world has tracked the variants of COVID," he says. Those variants include Alpha, Beta, Delta, Omicron and subvariants. But HIV is much more variable. "There are more variants of HIV in one person's body within days after infection than all the variants of COVID." That means that even as a vaccine is being developed to attack HIV, the virus may be mutating out of its reach.

A vaccine's job is to teach the immune system to recognize the disease and create antibodies to fight it off. So far, that hasn't worked with HIV.

"AIDS integrates into the immune system. It mutates incredibly rapidly, making it a moving target for the immune system," says Dr. Bruce Walker, director of the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard, which brings together scientists and engineers to better understand the immune system. "Meanwhile, the immune system is being destroyed by the virus itself."

Another factor that helped the rapid development of a COVID-19 vaccine, one not seen in HIV, is that the body's immune system, on its own, helps most patients recover. Of the 663.6 million people across the globe who had confirmed cases of COVID-19, 6.7 million have died since the start of the pandemic, according to WHO. Even before vaccines were available, most people recovered from COVID-19. The vaccines have improved their odds of not being infected, or of recovering if infected. "Our current [COVID-19] vaccines teach the body's immune system to do what it does naturally, clear the virus, only faster," says Warren.

"But no one clears AIDS naturally," he says. "With HIV, we're trying to create a vaccine to do something nature doesn't do by itself." People don't get over HIV infection the way they get over the flu or even COVID-19.

Instead, they live with HIV, thanks to new medications that bring the viral load down to undetectable levels. And PrEP medications, when taken correctly by uninfected people, can prevent new infections.

Isn't that enough, even without a vaccine? Why continue the search for AIDS' holy grail if PrEP can stop the spread of disease?

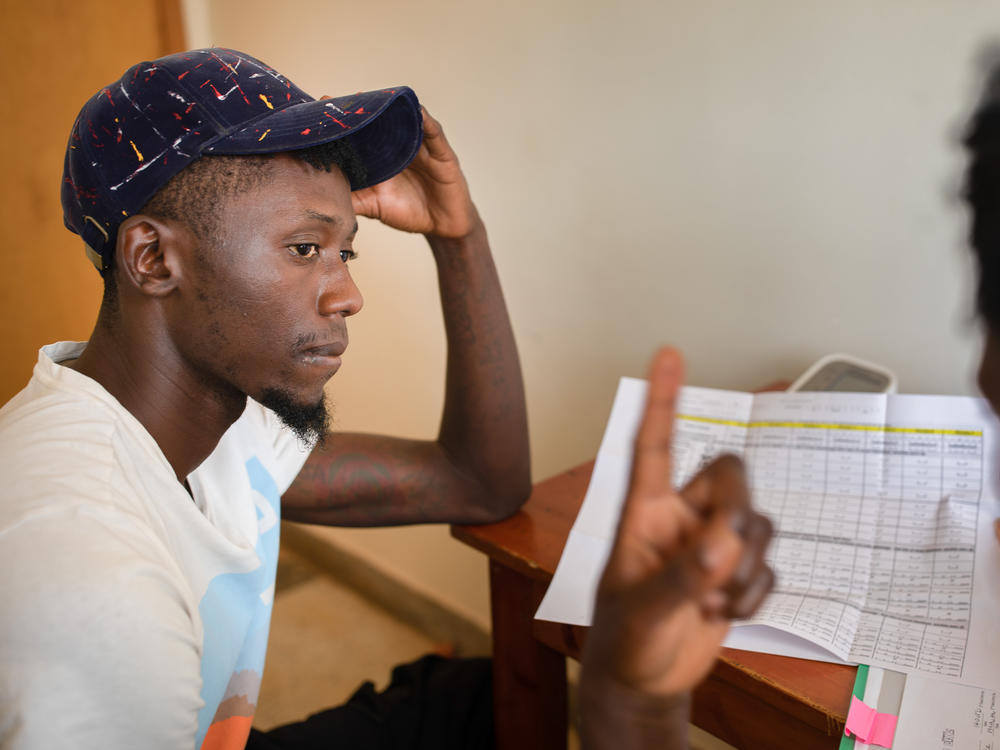

"The reality is that, yes, we do still need a vaccine," says Walker. "In parts of the world where AIDS is still most prevalent, PrEP is not always available." While the cost of PrEP has gone down in most low-income countries to less than $100 a year, it can be hard for those in remote areas to access the drugs, and the persistent stigma of AIDS can make people reluctant to take pills. For others, it can be difficult or impossible to stick to the daily regimen of pills, or the every-other-month injection, required for the medication to be effective. "Theoretically, if everybody had access to PrEP and everybody took it religiously, we might not need a vaccine. But humans aren't perfect."

While the failure of the Johnson & Johnson HIV vaccine was disappointing, no one is giving up. "You can't work in HIV if you don't maintain some optimism," says Warren.

There are flickers of hope. In March, for example, the National Institutes of Health launched a small, early trial of three experimental HIV vaccines using new messenger RNA (mRNA) technology, which was used in developing the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines.

Buchbinder says that the HIV Vaccine Trials Network, an international collaboration focused on the evaluation of vaccines to prevent transmission of the virus, has "a whole portfolio of vaccine trials to test." They're small, early trials, not yet close to determining if they're effective at stopping HIV transmission in large numbers of people. But "we've learned an enormous amount from every [HIV vaccine] trial," she says. "I'm hopeful."

Susan Brink is a freelance writer who covers health and medicine. She is the author of The Fourth Trimester and co-author of A Change of Heart.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.