Section Branding

Header Content

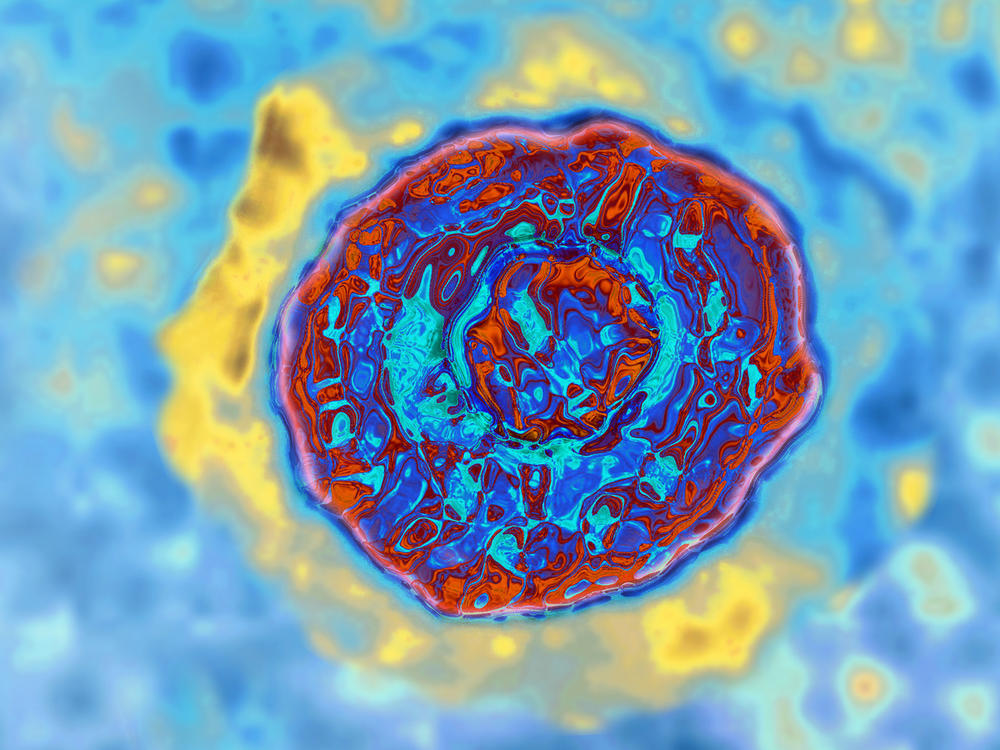

Hep C has a secret strategy to evade the immune system. And now we know what it is

Primary Content

How do viruses do their job of infecting humans? Some of them are experts at evading the immune system so that it won't knock them out.

Take hepatitis C, a sneaky and potentially deadly viral infection of the liver that is transmitted by contact with human blood – for example, through needles, sex and childbirth.

Scientists have known for a long time that hep C can hide from our immune system. While the immune system might attack the invading virus at first, leading to mild symptoms like fever or fatigue, the virus eventually hides so the immune system gives up the chase. Which is why most patients with hep C never show symptoms.

That gives hep C plenty of time to replicate and spread throughout healthy liver cells, leading to a chronic case of hepatitis C.

"We have this constant battle going on with these viruses," says Jeppe Vinther, a professor of biology at the University of Copenhagen who studies hepatitis C. "We are trying to defeat them and they are trying to avoid being detected and defeated."

But scientists didn't know how hep C pulled off its hiding trick. A new study led by Vinther and published in the journal Nature offers an explanation.

The cap is the key

So how does hep C do it? The virus uses standard villain fare to evade detection: a mask.

Hepatitis C is an RNA virus – one of several viruses that rely on their RNA instead of their DNA to carry information needed to take over the body's healthy cells. Other RNA viruses include measles, mumps, influenza and SARS-CoV-2.

RNA molecules in our body have a protecting group of DNA building blocks at their end known as a cap. These caps have various functions, including sending a message to our immune system: Leave us alone! Do not destroy us!

Since RNA viruses lack caps, once they invade our body, says Vinther, the cell control alarm bells go off and the immune system is activated to kill the foreign RNA.

This new study shows that when your body is infected with hep C, the virus attracts a cap for its RNA – like the protective cap on the body's own RNA. The researchers don't know exactly how the hep C virus does this — one of the many mysteries about viruses.

What's extra sneaky is that hep C uses something that's already in our body as its cap — a molecule known as FAD. With this handy mask, hep C fools the immune system into ignoring it. Unchecked, it can replicate and infect the liver.

The study shows that this cap could also play a role in enabling the virus's RNA to multiply in infected cells and spread throughout the body.

Do other RNA viruses use similar tricks?

Selena Sagan, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of British Columbia who was not involved in this study, says that this study reveals "a novel strategy viruses use to hide from our antiviral defense." She's interested in whether other RNA viruses do the same: "If hep C is doing it, what other viruses are using a similar strategy?"

Indeed, Vinther says the next steps for his research will be to look at other RNA viruses to see if they use a similar cap.

And that additional research could lead to benefits for humans. While FAD, the hep C cap, has many functions in our body, human RNA does not use FAD as a cap. This means scientists could use the FAD cap to target a specific virus. "This can potentially be used to detect viral infection or even interfere with the viral replication," says Vinther. "We have some ideas that we will test, but for now these are not tested and quite preliminary."

Using caps as a way to track and diagnose hep C could prove beneficial, given that many cases of chronic hep C go undetected and that only about 15% of patients are treated according to the World Health Organization. And without detection and treatment, the hep C virus has time to cause significant liver damage and even death. The yearly death toll for Hep C is an estimated 290,000.

But these findings are not going to be a boon for better treatment for hep C in particular. For those diagnosed with hep C, there's a very good oral treatment that's 95% effective — although as NPR reported in June, getting treatment isn't always easy because of the expense.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.