Section Branding

Header Content

'American African' identity is explored by U.S. artist with Ghanaian/Nigerian roots

Primary Content

How do I describe my cultural identity: African American or American African?

As someone grew up in a Congolese family in Nashville, Tennessee, this is a question I often asked myself.

Despite being born and raised in the U.S., I felt as if I belonged to my parent’s home country of the Democratic Republic of Congo more than Nashville, where I grew up. Going to school in a predominantly white environment as a child, the idea of living in an African country like the DRC felt like a dream come true to me.

I strongly admired the focus of community found within my parent’s home country and longed for that in Tennessee.

Yet when I do visit Congo, I know I’m not fully a part of the culture. If my accent when I speak French doesn’t give it away, locals could tell I was American from a mile away by my American-style dress and friendliness.

And even though I felt at peace when I was with the African American community in Nashville, I still felt like an imposter. I sometimes felt that because I wasn’t fully familiar with African American culture, Black people in Nashville thought I wasn’t “Black enough.”

Yet I did find similarities in both communities — in the strength of family and in the idea of reclaiming power from colonial rule.

So I was interested in learning more about the “Touch Products” exhibit, a collection of a dozen or so works of art by Africanus Okokon, a Rhode Island-based artist who is the American-born son of a Ghanaian mother and a Nigerian father.

Touching two cultures

“Touch Products” is the name of a popular cleaning product in Ghana.

The art uses all kinds of reclaimed objects in collages and video installations — for example, fragments of billboards for a popular rice product in Ghana (where Okokon often visited as a child).

The title has many meanings. Okokon’s art touches on connections between his American upbringing and his African roots. In a zoom interview with NPR, he explains: “Each object in the gallery has been touched by human hands at some point and used for a purpose that is different from the purpose of making a contemporary artwork.”

The show reflects what Okokon calls his “American African” identity, a term used by a friend during a conversation. But he says that the show isn’t just about him.

“Knowing about my identity isn’t going to make the work more understandable, transparent or clear,” says Okokon.

What is clear is that his art has a lot to say — and the interpretation is up to the visitor.

From my perspective, several of the pieces of art really resonated with my dual identity.

An artist's sampling: barbershop posters, sea chests

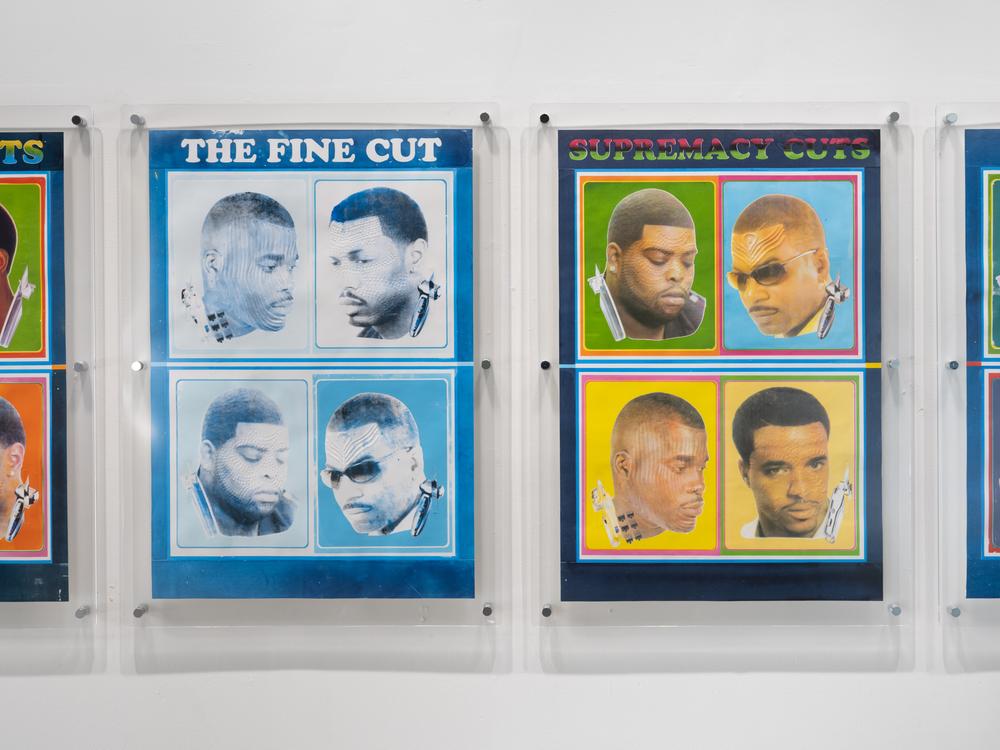

Okokon uses the term “sampling” to refer to his use of historic artifacts to connect African American and African cultures. Inspired by Ghanaian barber shop posters, Okokon created his own barbershop posters using African American men with West African scarification patterns across their faces. Okokon used beads and pieces of wires to create and replicate the scars on the posters. In both cultures, the barbershop is a communal gathering place.

One of the most impressive parts of the show: his collection of wooden sea chests, like those used by Ghana’s British colonizers. Only Okokon turns these chests into impromptu trophy cases by placing inside them statues modeled after Ghanian’s famed brass figures. He is taking ownership of the colonial era chests and using them to showcase the great statuary art of his mother's homeland.

Okokon worked with a group of artists and artisans from Kumasi, Ghana, to re-create the sculptures, using 3D scans to enable them to create brass versions.

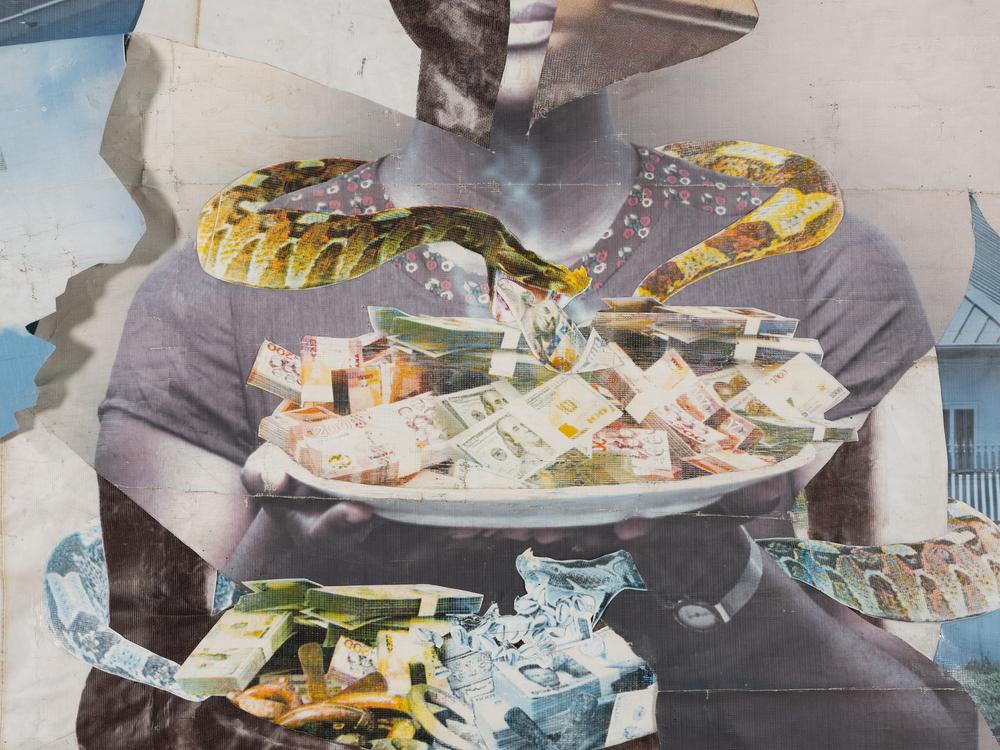

And then there'a the massive Breadwinner collage, roughly 12 feet by 7 feet and depicting a woman holding plates of money. The collage is where he incorporates parts of billboards for Aroma Rice, a beloved staple of Ghanaian cuisine. Okokon used a photo of his mother for part of the face of the women.

To my mind, that’s a way of paying homage to the roles of mothers in both African and African American cultures — strong women who raise their kids, perhaps prepare the rice for family meals and often keep the household afloat with their earnings.

And if you're wondering what the snake is doing wrapped around the mom — it's a symbol of scamming in Ghana. If you ask me, moms are pretty good at resisting scammers.

The public can view Touch Products through August 18 by contacting at the Von Ammon Gallery.