Section Branding

Header Content

Fear The Vibe Shift: Are We Entering A Recession?

Primary Content

It's being whispered and murmured about. The president is facing questions about it. Business leaders and investors are already bracing for it. The specter of recession is once again rearing its monstrous head.

It's feasible that the economy could chug along without any bumps or crashes. But boom-and-bust cycles remain a seemingly inescapable feature of capitalist economies. Some countries have done well avoiding busts. Starting in 1991, Australia had a run of almost 29 years without a recession, the longest stretch of economic growth of any nation in modern history. That ended in 2020, when the pandemic led to a big contraction — and Australia (briefly) succumbed to the beast.

While Australia had zero recessions between 1991 and 2020, the United States had two, a mild one in 2001, amid the dotcom crash and the 9/11 terrorist attacks; and a catastrophic one known as the Great Recession, between 2007 and 2009. Since 1854, the first year for which we have official economic data, the United States has experienced 35 recessions.

The National Bureau of Economic Research's Business Cycle Dating Committee is the official body that keeps track of recessions in the U.S. The committee has traditionally defined recessions as "a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months." However, it sort of fudged this definition when it declared that the pandemic downturn was a recession. The pandemic recession lasted only two months — the shortest recession in American history — but, the committee says, "the drop in activity had been so great and so widely diffused throughout the economy that the downturn should be classified as a recession even if it proved to be quite brief."

Despite all the talk about the U.S. entering another recession, the unemployment rate of 3.6% remains historically low, job growth remains strong, and, notwithstanding inflation, consumer spending continues to be like a firehose. That said, the U.S. economy shrank by an annualized rate of 1.4 percent in the first quarter of 2022, which means we may already be well on our way to the technical definition of a recession, albeit maybe a teeny-tiny one.

Why do economies experience recessions? The field of macroeconomics does not offer a crisp answer. Economists are divided. If there was one unified explanation, it would basically be s**t happens. But, despite its lack of consensus and the fact that each new recession seems to alter fundamental thinking about what causes recessions, macroeconomics still offers some important insights that can help us think about what's happening in the economy right now.

Vibe Shift

Much of modern thinking about recessions begins with the Great Depression, which has a name that belies the fact that it was really two of America's worst recessions back to back (depressions don't really have a formal definition; they're basically just really, really bad recessions).

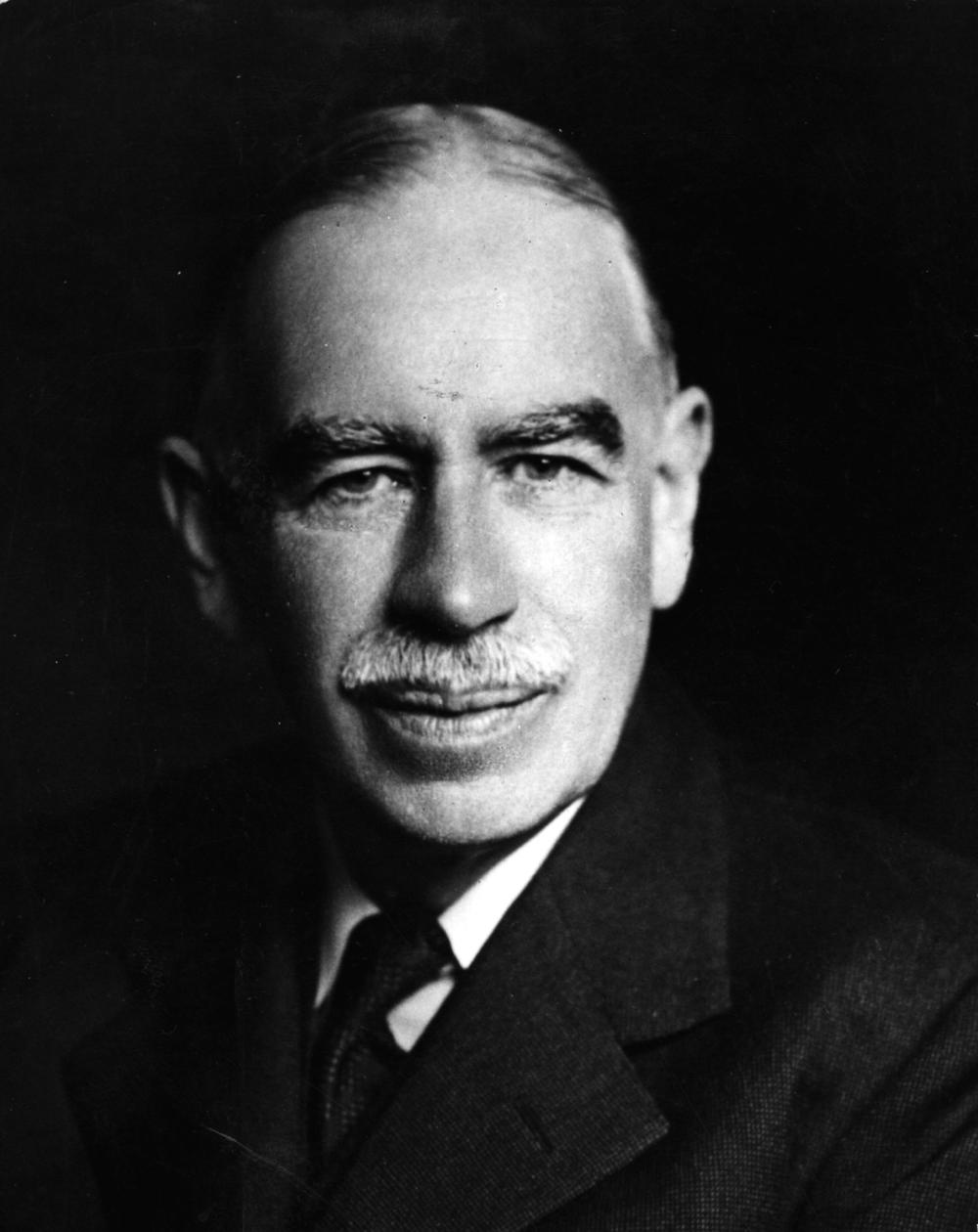

When the Great Depression hit, old-school economic theory, with its gospel of perfect free markets populated by hyper-rational market actors, had a hard time explaining what was happening. Enter: John Maynard Keynes.

For Keynes, free markets were riddled with imperfections that could conspire to lower prosperity for everyone. One important imperfection: our "animal spirits." Keynes posited that people aren't perfectly rational, especially in times of distress or panic or tremendous uncertainty — like during and after the stock market crash of 1929. Instead, Keynes said, we often make investing, spending, saving, and many other decisions based on our animal spirits: our feelings, emotions, beliefs, and psychological quirks.

Bad things happening in the world can lead to a dark turn in animal spirits. In modern parlance, you might call it a "vibe shift." Fear and pessimism, bad vibes if you will, can become contagious. Investors and business leaders and consumers can pull back and that causes a fall in aggregate demand — the total spending on goods and services in an economy. When the economy contracts, Keynes said, it won't necessarily self-correct and fix itself (as classical economists believed) — and lots of people can lose their jobs as a result. The solution, Keynes said, was for the government to step in, to fill in the spending hole created by the private sector with deficit-creating stimulus, and provide the confidence needed to get the economy chugging along again.

[Editor's note: This is an excerpt of Planet Money's newsletter. You can sign up here.]

Animal spirits are a hard thing to measure, but economists conduct periodic vibe checks by polling consumers and businesspeople to see how confident they are about the future. The thinking is that what people say they believe can be an important indicator of whether a recession is about to occur. The University of Michigan publishes a popular survey aimed at measuring consumer sentiment. It shows that after the pandemic hit, there was a vibe shift. Animal spirits went to a dark place. When the government stepped in with huge rescue packages to stabilize the economy, the mood started to improve.

But people's mental states never quite recovered to pre-pandemic levels, and starting in April 2021, they began to turn more negative again. Even after we got vaccines and treatments, the vibes only got worse, in large part because of supply chain problems, global instability, the persistence of COVID, and inflation. Earlier this month, the University of Michigan's gauge of consumer sentiment fell to its lowest level in more than a decade. The trend in gloomier animal spirits is one sign that a recession is stampeding towards us.

Other Explanations For Recessions

Some economists shrug at the idea of animal spirits and rely on explanations for recessions that see humans more as rational actors responding to economic challenges. As opposed to Keynesians, who tend to find the cause of recessions in failures of the private market, many of these economists tend to find the cause of recessions in government mismanagement of the economy.

Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, in their book A Monetary History of the United States: 1867-1960, famously argued that it was the U.S. Federal Reserve, pursuing a boneheaded monetary policy, that ultimately caused the Great Depression. When the stock market crashed, chaos spread through banks, and America entered a deflationary spiral, the Fed should have printed money, rescued banks, and stabilized the economy. Instead, the Fed did the exact opposite. It tightened monetary policy, failed to rescue banks, and removed money from the market. This, Friedman and Schwartz argued, made a bad situation much worse.

Today, there's a growing chorus — including The Economist magazine — blaming the Fed again for mismanaging the nation's money supply and leading us down a recessionary path. The Economist, as well as some prominent Democratic economists, argue that President Biden's $1.9 trillion spending package, the American Rescue Plan, overheated an economy that was already running hot, jumpstarting inflation. "As the White House hit the accelerator, the Fed should have hit the brakes," the magazine writes.

To be fair to the Fed (and the White House), it was hard to predict what the economy would do during the pandemic. Even more, for decades, prominent economists have cried wolf about inflation, claiming it was just around the corner yet it always failed to materialize — so it was hard to believe it would come roaring back.

Still, by letting the inflation genie out of the bottle, the Fed will now be forced to do the hard work of putting it back in. That could mean raising interest rates to a level that causes a big decline in spending and sparks a recession.

Supply Shocks

Many economists, however, argue the government is not responsible for the ultimate cause of the current economic malaise. They point to another historic source of recessions: supply-side shocks — or disruptions to business and production that often have nothing to do with decisions made by a nation's leaders. The pandemic has been one huge disruption, and with issues like COVID-related lockdowns in China hurting manufacturing, it continues to be.

Another huge disruption has been Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and the fallout in energy markets. According to one analysis, over the last 50 years, every time that oil prices rose 50% above trend, a recession followed. That, unfortunately, is what America (and the rest of the world) has been facing over the last few months.

So, are we heading into a recession? Darkening animal spirits — or bad vibes — suggest we may be. Fed policy suggests likewise. Ditto continued turbulence with COVID, and sky-high oil prices. In short, despite low unemployment, continued job growth, and other signs of economic health, there are warning signs flashing that a recession is coming, if it isn't already here.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.