Section Branding

Header Content

Why the American Dream is more attainable in some cities than others

Primary Content

Like most gyms, InnerCity Weightlifting in Boston offers one-on-one training sessions for people to shed pounds and get swole. But behind the dumbbells and treadmills is a deeper purpose: the gym was founded with the mission of providing opportunities for people at risk of poverty and incarceration — and helping them forge friendships with wealthier people.

InnerCity Weightlifting (ICW) does this by recruiting people who are economically disadvantaged, quite often fresh out of jail, and offering them a pathway to become trainers. The gym then pairs these new trainers with well-to-do clients.

"At ICW, through our career track in personal training, we help create economic mobility for people in our program as they begin earning $20-$60 per hour training clients from opposite socioeconomic backgrounds," writes Jon Feinman, the founder and CEO of the nonprofit gym. More importantly, Feinman says, their program creates bridges between people from different walks of life and forges lasting friendships between many participants. "The people in our program gain access to new networks and opportunities, while our clients gain new insights and perspectives into complex social challenges."

It pays to have friends in high places. That's no secret. But a pair of groundbreaking studies published today in the peer-reviewed journal Nature substantiates this in a profound way, showing that cultivating these kinds of relationships is crucial for upward mobility in America. They're part of a new research project that shines a spotlight on why the work of organizations like InnerCity Weightlifting is so important and suggests a path forward for revitalizing the American Dream.

The studies are by Harvard economist Raj Chetty and a team of nearly two dozen other scholars. They crunch data from more than 70 million Facebook users with 81 billion friendships to provide first-of-their-kind insights about the social relationships dotting America.

These online connections, the scholars say, give us an exciting glimpse of real-world relationships. Relationships that are formed in an unequal society, where the advantaged and disadvantaged often move in different social circles, due largely to where we grow up, the schools we attend, the jobs we do, and the activities and organizations we participate in.

The scholars find that the exact places that have more connections between low-income and high-income folks also have much greater rates of upward mobility. And they provide evidence that these cross-class relationships are the reason why low-income folks are much more likely to climb the economic ladder.

Beyoncé Drops Another Banger

For those who haven't heard of him, Raj Chetty does cutting-edge research that crunches humongous datasets and provides compelling evidence to address some of America's most stubborn problems: poverty, inequality, and declining opportunities for people to achieve the rags-to-riches success story of American folklore.

We at Planet Money have crowned Raj the Beyoncé of economics. And, wouldn't you know, within days of Queen Bey releasing a new album, Raj releases this incredible research project. Coincidence? We think not.

Last week, Raj reached out and let us know about his new drop. He and his co-author Johannes Stroebel, an economist at NYU's Stern School of Business, were kind enough to walk us through it over a Zoom call. It was like we got exclusive tickets to the nerdiest release party ever.

[Editor's note: This is an excerpt of Planet Money's newsletter. You can sign up here.]

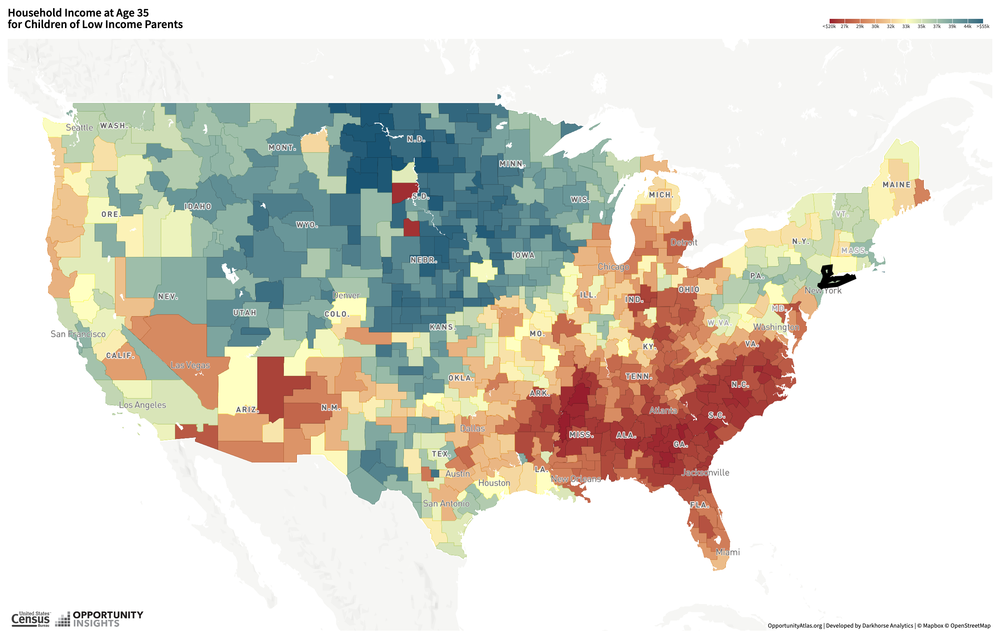

Raj says the story of this research project begins some years back, when he and his colleagues published a detailed, interactive map of America that shows the likelihood of kids climbing out of poverty in each zip code. They call the map — which is based on extensive work analyzing millions of IRS tax records — the "Opportunity Atlas."

Since undertaking this research project, Raj and his collaborators have been trying to figure out why the map looks like this. Why do kids in places like Silver Spring, Maryland, have a much better shot of rising out of poverty than kids in Little Rock, Arkansas?

The places where the American Dream is something close to pure fiction have a lot of bad things going on. They have high rates of poverty, significant inequality, a large fraction of single-parent households, bad schools, and other factors that might explain why they see a lower rate of upward mobility than other places.

"The big question is: why is the American Dream more alive in some places than others?" Raj says. "And, along the way, lots of folks talked about the idea that social capital — or who you're friends with, who you're interacting with — might be an important factor."

Social capital. It generally refers to the value of our relationships, with our family, friends, and broader community. Sociologists and political scientists have long found that these relationships matter a whole bunch for our well-being. But which types of relationships might give us a boost economically? And how do we clearly and precisely measure that?

You might not think of Facebook as the ideal measure of genuine friendships, but Raj and his team use it as a proxy to see the power of relationships formed in the real world. And they do a bunch of work cross-referencing and benchmarking this data with other sources, including national surveys. What's exciting, Raj says, is that the Facebook data matches other estimates of social relationships, "but it allows you to now zoom in" and see what these relationships look like in each zip code.

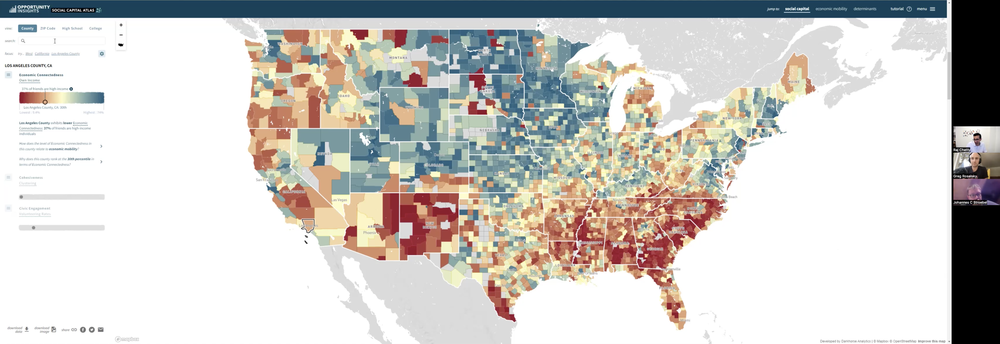

Raj and his team use Facebook data to create three measures of social capital. First is what they call economic connectedness, or the rate at which low-income folks are friends with high-income folks.

Second is what they call cohesiveness, or how tight-knit our social circle is, measured by how many of our friends are friends with each other.

Finally, the third measure is civic engagement, namely whether people belong to community organizations (in a famous book called Bowling Alone, Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam used this measure of social capital, looking at measures like how often bowlers participated in community bowling leagues).

The team finds that of these three measures, the only one strongly associated with upward mobility is economic connectedness. And it turns out it's a huge deal. "Social interaction across class lines is a key factor that predicts upward mobility out of poverty," Raj says.

It Pays To Have Friends In High Places

When explaining why friendships with high-income folks are so critical for low-income folks to get richer, Raj pulled up a multicolored map of America. At first glance, I thought it was the exact same map he had shown before, the Opportunity Atlas, which shows the likelihood of Americans rising out of poverty.

"No, this is actually a map of economic connectedness with Facebook friendships," Raj said. They call it the Social Capital Atlas. "And the fact that these two maps look the same to you is sort of the first result: It's exactly in the places where low-income people have lots of high-income friends that economic mobility is higher."

The fact that these two maps look similar isn't a coincidence. Raj and his colleagues find that there is something magical about cross-class friendships that causes people to rise up the income ladder. Even controlling for things like the quality of schools, racial segregation, the rate of poverty, and the extent of inequality in a community, economic connectedness has a huge amount of power in explaining rates of upward mobility.

Raj and his colleagues don't have direct evidence to explain exactly what it is about having economically diverse social circles that causes a community to see greater rates of upward mobility. Maybe it's because high-income people help their low-income friends get jobs. Maybe it's because high-income people serve as role models. Maybe it's because high-income people shape their friends' aspirations or self-presentation or norms or behavior.

But what they're able to document is that if you plop a kid from a disadvantaged background into a community with more economic connectedness, their income in adulthood will be, on average, 20 percent higher. That's huge. It's similar to the effect of going to a four-year college.

But, Raj notes, these effects aren't necessarily separate. Growing up in a place with lots of connections between high-income and low-income folks likely influences low-income folks to go to college, which is one of the many reasons why living in a more economically connected place might be giving people a boost.

But There's A Problem

While there seems to be something magical about economic connectedness, the problem is that many communities across America don't have much of it.

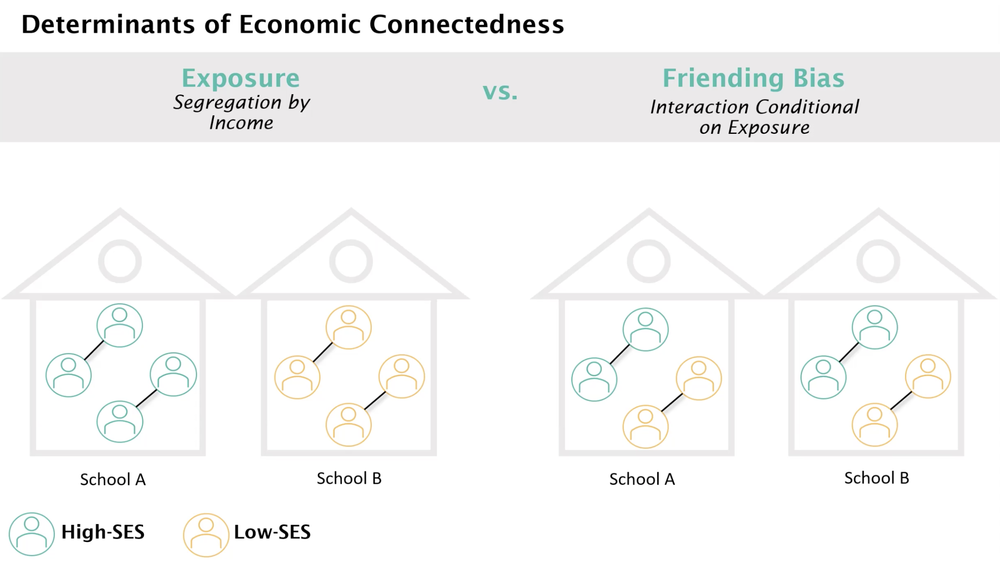

In a second study, Raj and this team examine why some communities are integrated across class lines and others are not. They find it boils down to two factors: exposure and "friending bias."

Exposure is pretty self-explanatory. How much do low-income people encounter high-income people in an area? Economic and racial segregation play a huge role in preventing unequal groups from interacting with each other in many communities.

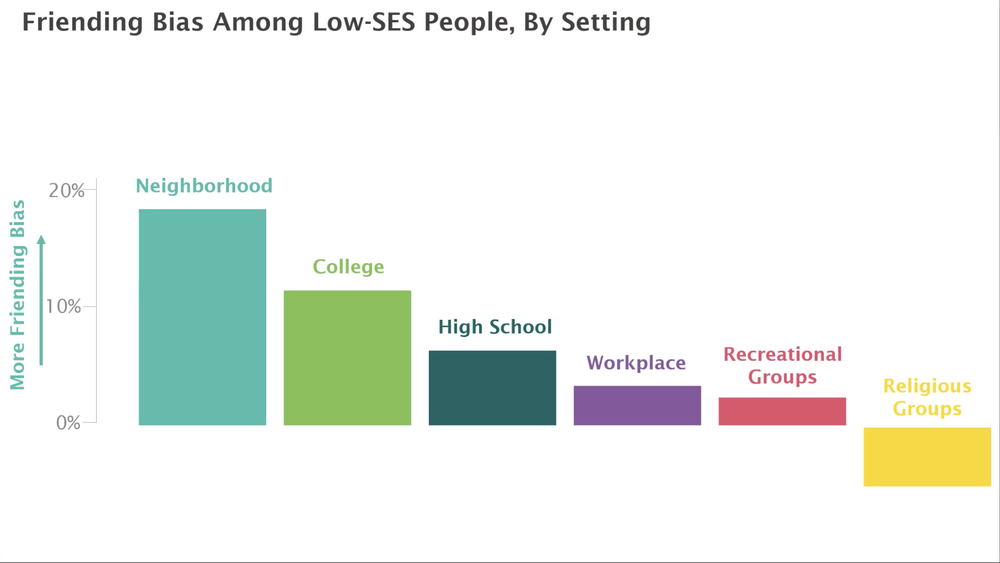

But the problem cuts deeper. Even if low-income folks do encounter high-income folks, there's a tendency for them not to become friends. The researchers call this "friending bias."

"Even if you somehow — and we're nowhere close to doing this — solve the economic segregation problem by perfectly integrating every school, every college, every zip code in America, so that they're all perfectly balanced by income, you would still have 50% of the social disconnect between the poor and the rich left because friending bias remains," Raj says.

But there's good news: the evidence strongly suggests that friending bias can be combated. There are some settings where friending bias is really low, like the workplace and recreational groups. In churches, mosques, and synagogues, they find, it actually seems to be slightly negative, suggesting that low-income folks tend to form friendships with high-income folks at a really high rate in those settings.

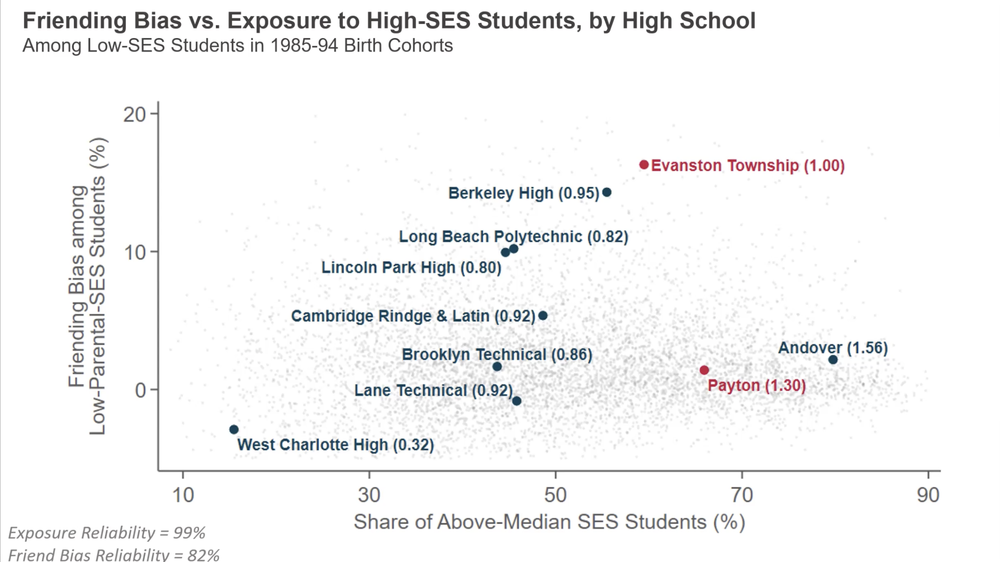

Digging through the data, they find that the same people who exhibit friending bias in one setting often don't show it in another. They also look at high schools across the nation, and they find that schools with similar demographics often exhibit wildly different rates of friending bias.

"It's actually about the setting," Raj says. In other words, it's not only possible to desegregate communities and institutions, it's also possible to foster friendships within them between people from different walks of life.

Raj says there's much that the government could do to economically integrate America, including building affordable housing in high-income areas, helping low-income kids go to high-income schools, and thinking deliberately about how to foster friendships in various institutions. That, this new research suggests, would go a long way towards revitalizing the American Dream.

But what's also exciting about this research project is it points to practical steps we can make in our own communities to forge friendships between people from different walks of life and help the disadvantaged become more prosperous.

Steps like the one taken by InnerCity Weightlifting in Boston. Raj and his colleagues actually shout-out the nonprofit gym at the end of one of their new papers. The gym has been operating for over a decade, and it's showing signs of success, with lower rates of recidivism and higher rates of upward mobility for its trainers.

"Along the way, something unexpected happened," writes Jon Feinman, the gym's CEO. "We had our paying clients — people paying our student trainers — visiting our students in jail when things went wrong. They were showing up in court to be a support. They started offering job opportunities to our students outside of the gym, and they paid for the children of our students to go to summer camp with their own children."

Not bad for a gym.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.