Section Branding

Header Content

To Come To The Rescue Or Not? Rats, Like People, Take Cues From Bystanders

Primary Content

Rats will enthusiastically work to free a rat caught in a trap — and it turns out that they are especially eager to be a good Samaritan when they're in the company of other willing helpers.

But that urge to come to the rescue quickly disappears if a potential hero is surrounded by indifferent rat pals that make no move to assist the unfortunate, trapped rodent.

These findings, reported Wednesday in the journal Science Advances, suggest that rats are similar to people in that they're usually eager to help, but bystanders can affect whether or not they'll take action in an emergency.

"We are constantly looking at others to see their reactions. And this is not a human thing. This is a mammalian thing," says Peggy Mason, a neurobiologist at the University of Chicago, adding that it's something she watches play out in the daily news.

"Police are standing by as their co-workers are kneeling on a man and killing him and not doing anything," she says.

Social psychologists have been studying the effect of bystanders on helping behavior since the New York City murder of Kitty Genovese in 1964. Back then, The New York Times published a dramatic story saying that 38 people saw or heard the horrific attack but did nothing to stop it. The newspaper later conceded that the account had "grossly exaggerated the number of witnesses and what they had perceived."

Nonetheless, the account inspired decades of research on what came to be called the bystander effect — the idea that people are less likely to act in a crisis when they are in the presence of others than when they are alone.

Generally, Mason says, experimenters have tested out this idea by putting people into contrived, fake emergencies. That lets researchers see what people do when they are on their own versus what they do when they're with people who are secretly actors, playing the part of passive bystanders.

"With the addition of more and more bystanders, the likelihood of helping goes progressively lower," Mason explains. "It's in every textbook. It's a pillar of modern psychology."

Until recently, though, the bystander effect had only been tested in humans. And Mason studies rats.

Her lab's latest experiments got their start a few years ago when Mason happened to read a book called The Unresponsive Bystander: Why Doesn't He Help? by Bibb Latané and John Darley, who did the first studies on the bystander effect in the 1960s.

Mason talked about this book with her lab colleagues, and one of her students, John Havlik, suggested they try to repeat these experiments, using rats.

"I said, 'It won't work out.' And he basically wouldn't take no for an answer," says Mason, who explains that Havlik just went ahead and did some studies anyway.

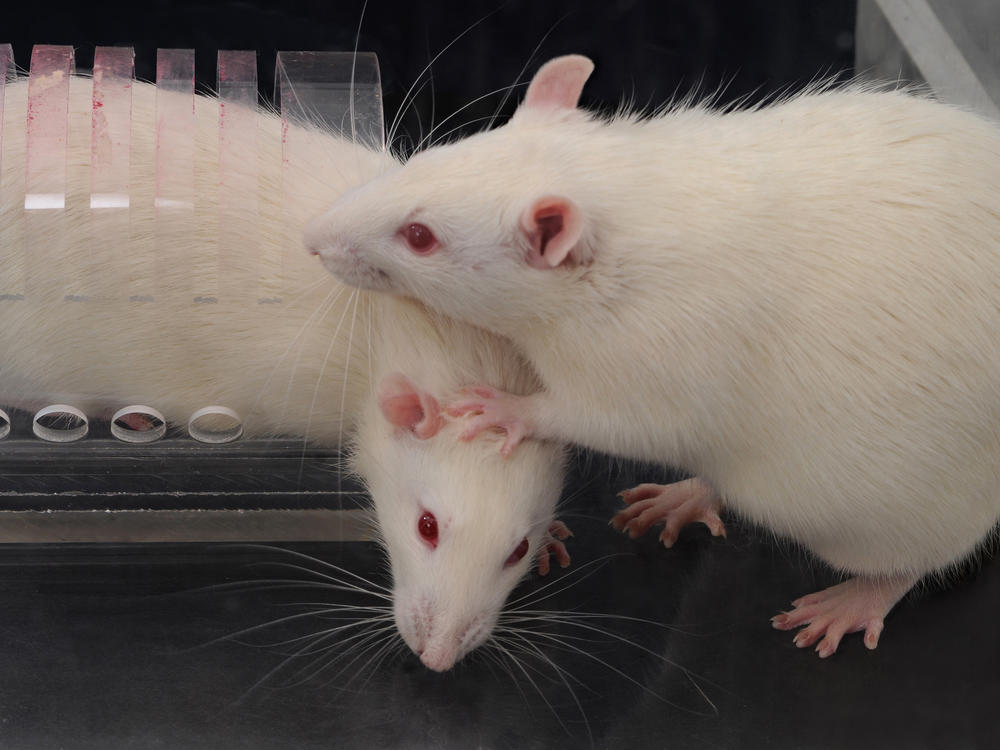

She and her colleagues had previously shown that rats are normally enthusiastic helpers. If a rat encounters another rat that is trapped in a holder made from a clear acrylic tube, the free rat will explore the tube and figure out how to release the trapped one. It will do this over and over again, even for rat strangers (as long as the trapped rat belongs to a strain that they have lived with previously). "They don't have to know the individual rat, but they have to know the type of rat," Mason says.

These rat rescuers seem to be motivated by the internal distress they feel at another's plight — because when researchers gave the free rats a "chill pill," an anti-anxiety drug — the animals would no longer work to release their trapped companion. (The researchers know it's not that the drug made the animals sluggish, Mason says, because the drugged rats would still happily work to open up a tube full of chocolate they wanted to eat.)

So, to test out the bystander effect in rats, the researchers trapped one rat in the acrylic tube, as they usually did. Then they added to the enclosure not just one free rat but two or three.

When all but one of the free rats was given the anti-anxiety drugs that caused passivity in the face of another's need, the researcher saw a definite effect on the non-drugged rat's willingness to help.

"He'd help once. He would not help again," says Mason, who says the rat would not help the next day or the day afterward as a rat normally would.

"It is essentially as though this rat says, 'Well, you know what, I helped yesterday. No one cared — not doing that again.' And that's amazing," Mason says.

She notes that when none of the rats was drugged into passivity, rats that had other free companions started to help much more quickly than they did when alone, suggesting the companions' positive reactions may have spurred on the helpful rats.

"That's not something that derives from culture or from teaching or from Sunday school or from learning," Mason says. "It derives from our biological inheritance as mammals."

Mark Levine, a social psychologist at Lancaster University, says it's interesting that, left to their own devices, rats are quite helpful.

"That's pretty much the same as humans. That's what our research shows, that actually, despite what people think, humans are incredibly helpful in real-life situations," Levine says. "The bystander effect shows that under some circumstances, the presence of others reduces the likelihood of helping somewhat. It doesn't mean that humans don't help."

He and his colleagues recently used video from surveillance cameras to show that in nine out of 10 public conflicts that happened in the real world, at least one bystander — but typically several — did something to help. And research shows that in violent or dangerous emergencies, the presence of others can enhance the willingness to step in.

Levine notes that in the rats, the bystander effect was produced by introducing something unnatural into the situation — the drug — which is a bit like how the bystander effect in people is produced in contrived experiments using passive actors.

"Helping only begins to fall away when something almost artificial is introduced to try and undermine the natural propensity of rats and humans to take care of each other if they possibly can," Levine says. "It seems that helping is actually natural amongst rats, just like it's natural amongst humans, which I thought was a really interesting thing to see."

He says that in the rat study, behavior seems to have been influenced only by rats that belong to familiar strains, and not unfamiliar kinds of rats. In that, too, he says, rats appear to be similar to people.

"When we are in situations where we are uncertain about the nature of what's happening in front of us, we tend to look to other people for information," Levine says. "But we don't just take any information. We only take information from others we believe to be like us."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.