Section Branding

Header Content

What A Nasal Spray Vaccine Against COVID-19 Might Do Even Better Than A Shot

Primary Content

The primary goal of a COVID-19 vaccine is to keep people from getting very sick and dying. But there's another goal — to prevent the spread of the disease — and it's not clear most vaccine candidates currently under development can do that.

Some scientists think they can solve that problem by delivering a vaccine as a nasal spray.

"The majority of vaccines — in fact, all of the ones that are currently in clinical trials — are delivered via the muscle," says Frances Lund, an immunologist and vaccine developer at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. That muscle is typically the deltoid in the upper arm. An injection into muscle tends to give the strongest immune response. That's why most vaccine developers start there.

"You will get a systemic response, but you will not get a local response with that," she says. By systemic response, Lund is talking about generating antibodies that circulate systemically — through the blood to all parts of our bodies.

But for a respiratory virus like a coronavirus, the infection typically starts in the nose or throat, and an infection can take hold there before the systemic immunity kicks in.

The injected vaccine might protect people from getting terribly sick, but people still might have virus in their nose that could spread to others.

Putting a vaccine directly into the nose offers another kind of immunity that occurs primarily in the cells that line the nose and throat.

"You still get systemic immunity if you deliver it via the intranasal route, so that doesn't go away, and you add a level of immunity that you don't get with an intramuscular vaccine," she says. "And that immunity is local."

The systemic immunity will keep one from getting sick and the local immunity means it will be harder for the virus to start an infection inside your nasal passages — a pocket of infection that could easily spread to others via a breath or a sneeze. Lund is working with a company called Altimmune to make such a vaccine.

There would be no need to worry about vaccinated people shedding virus and infecting others if a new vaccine were totally effective and everybody got vaccinated. But that's an extremely unlikely scenario for several reasons.

"Even if we had adequate supplies of vaccines, there are two problems," says Michael Diamond, a vaccine developer at Washington University. "One, some people are not going to take a vaccine. And then there's a fragment of the population that just won't mount good responses to a vaccine," meaning the body may not make antibodies that will protect them.

A vaccine that prevents virus spread is desirable, but not always technically feasible.

Diamond is also working on vaccine administered via the nose, which he describes this month in the journal Cell.

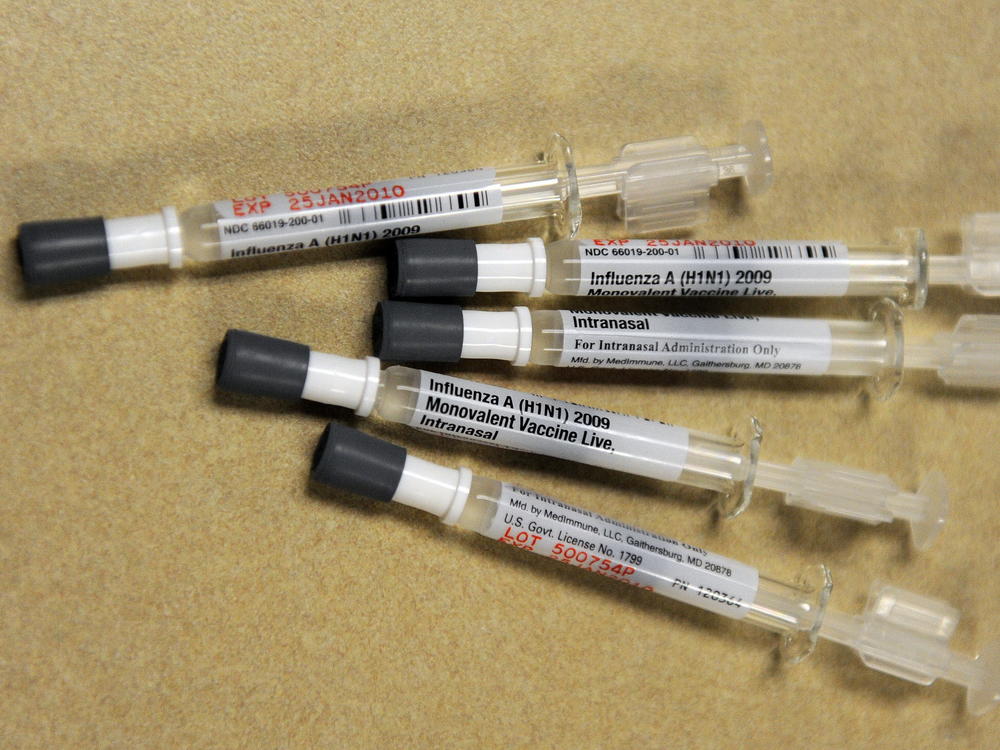

Although nasal spray vaccines aren't common, Diamond says, some do exist against certain other illnesses.

"There's already a flu vaccine called Flumist, which is used now," he says. "So we expect that technology that's used for existing nasal sprays could be applied to this one."

You can contact NPR science correspondent Joe Palca at jpalca@npr.org.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.