Section Branding

Header Content

Opinion: Public Health Leaders Deserve More Respect

Primary Content

As a veteran who served back-to-back tours in Iraq, I initially cringed when commentators compared the COVID-19 crisis to wartime — no bullets, no blood and no one volunteered for this.

But after my months of reporting on the pandemic, it has become painfully clear this is like war. People are dying every day as a result of government decisions — and indecision — and the death toll is climbing with no end in sight.

Less than six months into the pandemic, COVID-19 has already killed at least 181,000 Americans, more than triple the number who died in the Vietnam War, and far more than the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan combined.

We are all being asked to make sacrifices for the good of our country. And we're experiencing, as a nation, a deeply traumatic event. Like war, the toll will be felt for a long time.

In California, where I live, local public health officials are leading the front lines in this battle against COVID-19, dictating strategy, issuing orders and developing tactics to carry out that strategy. Every day, they make gut-wrenching calls to protect our health and livelihoods, even if those decisions may inflict initial harm on the economy or contradict politicians and popular opinion.

But instead of being celebrated for their difficult and dangerous work, as I was, they are now facing violent threats and political attacks from those who disagree with their tactics — such as requiring masks in public and ordering businesses and parks closed to prevent the spread of infection.

When I interview them, often late at night, I hear in their voices that familiar mix of emotions that often come with war: exhaustion, anxiety and devotion to duty.

"We've become easy scapegoats for people's fear and anxiety during COVID-19," said Dr. Gail Newel, the health officer for Santa Cruz County, who continues to face threats for issuing public health orders.

The latest — a menacing email sent to her in late July calling her a "communist bitch" — prompted local law enforcement to recommend she get a guard dog and firearm to protect herself. "That weighs very heavily," she said.

I can't imagine the burden. Although many of us serving in Iraq disagreed with the war, we remained dedicated to our mission and enjoyed broad support at home.

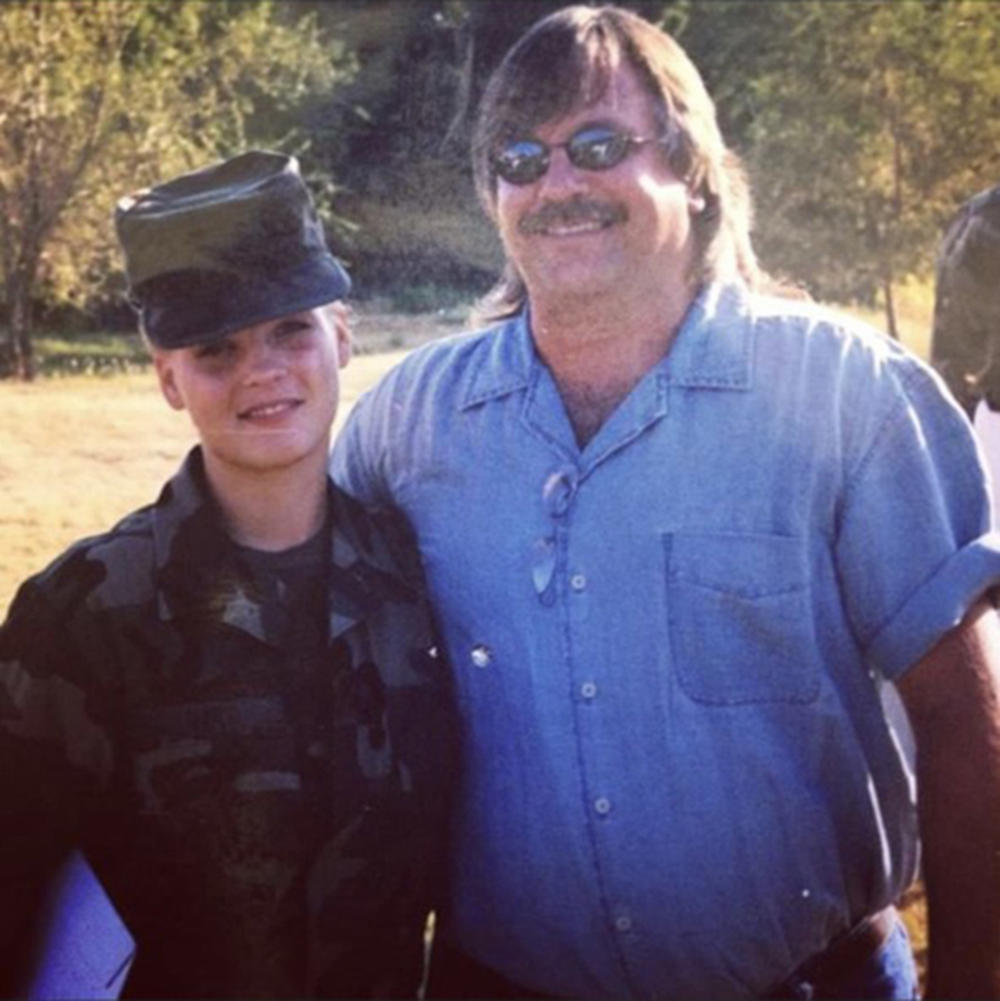

I joined the military as a U.S. Army reservist in 1999 and was deployed on active duty to Iraq in early 2003, when it truly was like the Wild West.

Serving first as logistics clerk and then the acting supply sergeant for a military police company out of San Jose, Calif., I helped ensure my military brothers and sisters had proper equipment. When the George W. Bush administration sent us to Iraq, for example, it did so without armoring our Humvees — a major failure that elevated our risk of being blown up by roadside explosives.

I returned home in July 2004 and spent years putting the battlefield behind me as I transitioned to a career in journalism. But living through COVID-19 has resurrected those feelings of being at war.

Now, just like then, there is an overall sense of fear and uncertainty because we don't know when the crisis will end. We aren't free to go about our lives as we once did and we yearn for the comforts we took for granted. We miss our loved ones we can't see.

We must remain hypervigilant to potential threats, and even make sure to don our "armor" when we leave our homes — except now it's masks and gloves instead of helmets and flak jackets.

There's something that happens when you're in a conflict zone — the air feels heavier. You can feel threats all around you, just waiting to strike. There's deep anxiety for what the future holds, and you wonder whether you'll be alive next week or next month.

Public health officers are shouldering the added anxiety that duty brings. For much of the pandemic, elected leaders have pushed responsibility — and blame — of reopening largely onto health officers in counties and states, who have worked for months without days off, giving up time with their families to attack this crisis head-on.

I have interviewed dozens of these local and county health officers in California. Some have broken into tears while talking with me, and worry chokes their voices as they lament problems with testing or explain how they don't have enough supplies or contact tracers to safely reopen. They felt rushed into lifting stay-at-home restrictions in May and June, yet they had no choice in the face of pressure from politicians and suffering residents and businesses. After years of severe underfunding, public health agencies don't have the money or resources to deploy an adequate response.

They're also wrestling with the guilt and trauma that come with making decisions that affect people's lives and livelihoods.

"It has been hard on all of us," acknowledged Sacramento County's health officer, Dr. Olivia Kasirye. "We're getting phone calls daily from people saying they're going bankrupt and they can't pay their rent and they have loved ones who are dying that they can't see."

I know how that feels, having been conflicted about our long-term strategy in the Middle East and the harm we inadvertently inflicted on innocent civilians. But I can't imagine being afraid of the people I signed up to protect.

Public health officials have become targets of aggressive and personal attacks. Some have seen their photos smeared with Hitler mustaches, while others have had their personal phone numbers and home addresses circulated publicly, prompting the need for round-the-clock security.

"Imagine treating American soldiers and military families with the kind of hatred and disrespect that local health officers are facing," said Dr. Charity Dean, unprompted, a day after she left her job as one of the top public health officials in Gov. Gavin Newsom's administration. "They're the ones taking all the risk, and it makes me angry to see how they've been treated."

Since the start of the pandemic, at least eight career public health officials in California have resigned, and more are considering it. But most are soldiering on.

Mimi Hall, Newel's boss and Santa Cruz County's top public health official, told me law enforcement is investigating a threatening letter addressed to her that was allegedly signed by a far-right anti-government extremist group.

In response, Hall considered retiring early. But she didn't want to abandon her troops and wasn't going to let fear stop her from doing her job. So she had a perimeter fence and home security system installed over the weekend — and reported for work promptly Monday morning.

Yes, we are waging a life-or-death battle in which innocent people are hurt, but it's these battle-scarred public health officers who are making deeply personal sacrifices to steer us to safety.

We commemorate military leaders with medals and parades. Why not treat our public health officials with the same level of appreciation?

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Angela Hart, correspondent for California Healthline, covers California health politics and policy in Sacramento and around the state.

Copyright 2020 Kaiser Health News. To see more, visit Kaiser Health News.