Section Branding

Header Content

As COVID-19 Vaccine Trials Move At Warp Speed, Recruiting Black Volunteers Takes Time

Primary Content

Black patients are some of the most reluctant to participate in clinical trials, according to FDA statistics. And their inclusion in the coronavirus vaccine trials has been a stated priority for the pharmaceutical companies involved, since African American communities, along with Latinos, have suffered disproportionately from the pandemic.

But the trials are moving at a pace that is unprecedented for medical research, with the Trump administration's vaccine acceleration effort dubbed "Operation Warp Speed." Yet recruiting minority participants into these ongoing trials requires sensitivity to a legacy of mistrust based on past and current medical mistreatment, and that trust-building cannot be rushed.

So far at least, participation by minority volunteers in coronavirus trials has increased only slightly, compared to usual low levels — and targeted outreach efforts to recruit more have been slow to launch.

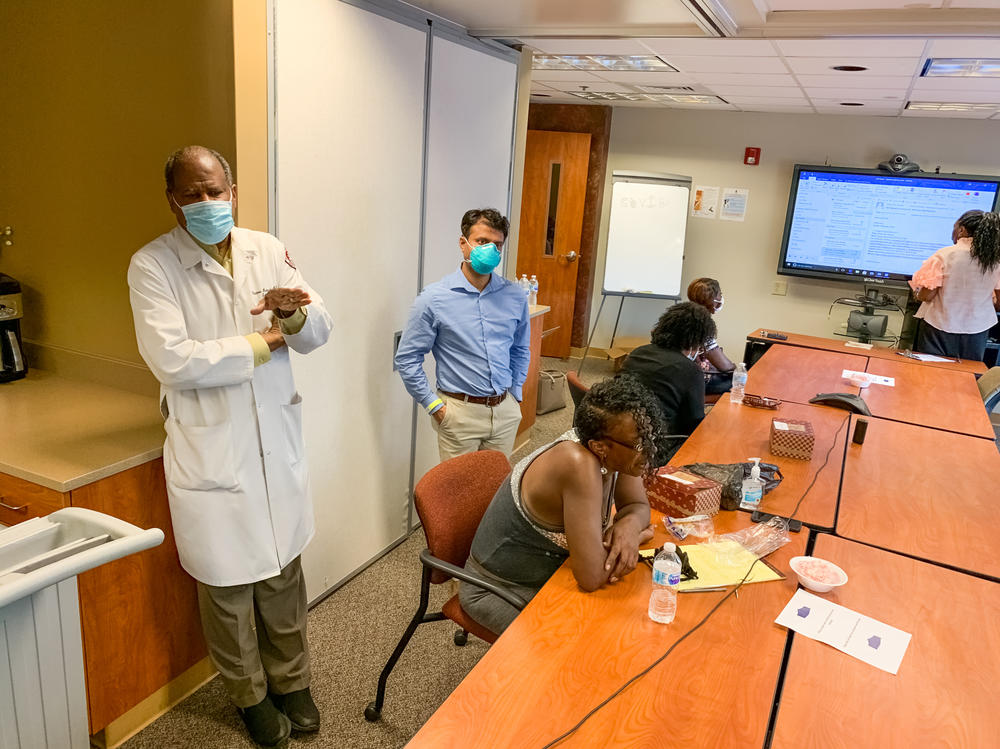

Some of that outreach is taking place at historically black colleges and universities, which are trusted institutions for many Black Americans. At Meharry Medical College in Nashville, researchers have started by setting up in-person meetings with patients they already know. Last Wednesday, half-a-dozen patients gathered in a cramped conference room on campus. They snacked on turkey sandwiches and potato chips and listened to the pitch from their physician, Dr. Vladimir Berthaud.

"What's the best hope to get rid of this virus?" he asks them.

"Vaccination," they reply.

Then Berthaud follows up: "So raise your hand if you would like to take the vaccine?"

Some hands shoot up, but not all.

"I ain't going to be the first one, now," says Lanette Hayes.

Katrina Thompson says she does eventually want to get a shot for protection against the coronavirus. She explains that she's especially worried about all the residents of her apartment building who don't seem to be doing the basics of covering their coughs.

"The word 'vaccination' don't scare me," she says. "The word 'trial' do."

Black Americans have reason to be suspicious — beyond the well-known Tuskegee experiments where Black men with syphilis were deceived and mistreated as part of an experiment that went on for decades. Even today, many Black Americans report ongoing mistreatment by medical providers.

Dr. Berthaud is recruiting patients for a clinical trial site he will oversee here in Nashville, and he would like more than 300 people of color to enroll. Berthaud, who is Black and from Haiti, appeals to a sense of duty.

"If you don't have enough people like you in those vaccine trials, you will not know if it works for you," he tells them. "You will not know."

For most of the current coronavirus vaccine trials, recruitment mainly takes place online — which often results in mostly white people enrolling.

That's why Meharry researchers are wooing Black patients with a personal invitation to take part. The problem is, they're not recruiting for the phase three trials currently underway. Meharry's first trial, for a vaccine candidate by Novavax, doesn't launch until October.

Meanwhile, other pharmaceutical companies are nearly done recruiting. Moderna says it chose nearly 100 trial sites for their "representative demography."

The company did not respond to requests for comment but is publicizing demographic statistics about the clinical volunteers every week. They're somewhat better than the typical clinical trial but still not a good representation of the diversity of the U.S.

For the coronavirus vaccine in particular, the National Institutes of Health has suggested minorities should be over-represented in testing — perhaps at rates that are double their percentage of the U.S. population.

"We say we want to have everybody included, but really the effort for the vaccinations — in a sense — are starting the same way they've always been," says Dr. Dominic Mack of Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta. He's working with the NIH to make sure people of color are included in COVID-19 research.

Mack says there are no shortcuts if medical research is going to reflect the diversity of the U.S. It takes time to build trust and meaningful relationships with people who have endured a history of abuse or neglect by medical providers, and exclusion from biomedical research and decision making.

"Now, that being said, the only thing we can do is what we're doing," he says — by which he means respectful, not rushed, outreach and dialogue.

The primary effort, called the COVID-19 Prevention Network, taps into four existing clinical trial networks that were designed to advance HIV research. Those networks are based in Seattle, Atlanta, Los Angeles and Durham, N.C.

One project announced this week will be led by Rev. Edwin Sanders II of the Metropolitan Interdenominational Church in Nashville. It will involve seven "faith ambassadors" and 30 "clergy consultants" in the African American community, who will work to help dispel myths and increase trust in the clinical trial process.

But Sanders cautions this is not about a hard sell. He says it's not his job to preach trial participation from a pulpit.

"We are not out beating the drum," he says, acknowledging that congregants may have legitimate concerns. "I am not going to do anything more than make sure people are able to make an informed choice."

There is a danger that lunging for big diversity goals could even spark a backlash, meaning minorities might be even less willing to participate, says professor Rachel Hardeman who studies health equity at the University of Minnesota.

It's important that the doctors doing the asking look like the people they're appealing to, she says.

"It's racial concordance," she explains. "It offers this feeling of, 'you know who I am, you know where I come from, you have my best interests at heart.' "

Historically Black medical institutions in the U.S. are uniquely positioned to do this work. While they haven't been on the leading edge of the vaccine trial recruitment, they intend to play an important part.

The president of Nashville's Meharry Medical College, Dr. James Hildreth, is, himself, an infectious disease researcher. But instead of overseeing the trial site being hosted on his campus, Hildreth has a more modest goal in mind: He plans to participate as a patient, and urge others to join him.

"I think my role is more important in advocating for people to be involved in vaccine studies than to be one of the leaders of the study," he says.

So at Meharry, Dr. Berthaud is the principal investigator. As lunch wraps up in the crowded conference room, he's managed to win over even the holdouts.

"Where is the line?" asks Robert Smith. "Where do we sign?"

Smith, with his young grandson in tow, didn't raise his hand at first when asked if he'd take the vaccine. But after listening to Dr. Berthaud, Smith agrees to participate in the clinical trial — for no other reason than the trust he has in Berthaud, his long-time physician.

"He's not only my doctor; he's proven that he cares about me," Smith says.

Convincing hundreds or thousands of Black Americans to sign up will be difficult. But even for those who don't participate, researchers hope their outreach efforts will at least result in more minorities ultimately agreeing to take the approved vaccine when it's available.

This story was produced in a partnership between NPR, Kaiser Health News and Nashville Public Radio.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.