Section Branding

Header Content

Vitamin C Fails Again As Treatment For Sepsis

Primary Content

Though attention has understandably been on COVID-19 over the last year, nearly as many people in the hospital have died with a different condition: sepsis. A study now casts doubt on a once-promising treatment for this disease.

In 2017, scientists thought they had found a remarkable advance. A researcher in Norfolk, Va., reported that a treatment involving intravenous vitamin C, thiamine, and steroids sharply reduced the risk of death in his sepsis patients.

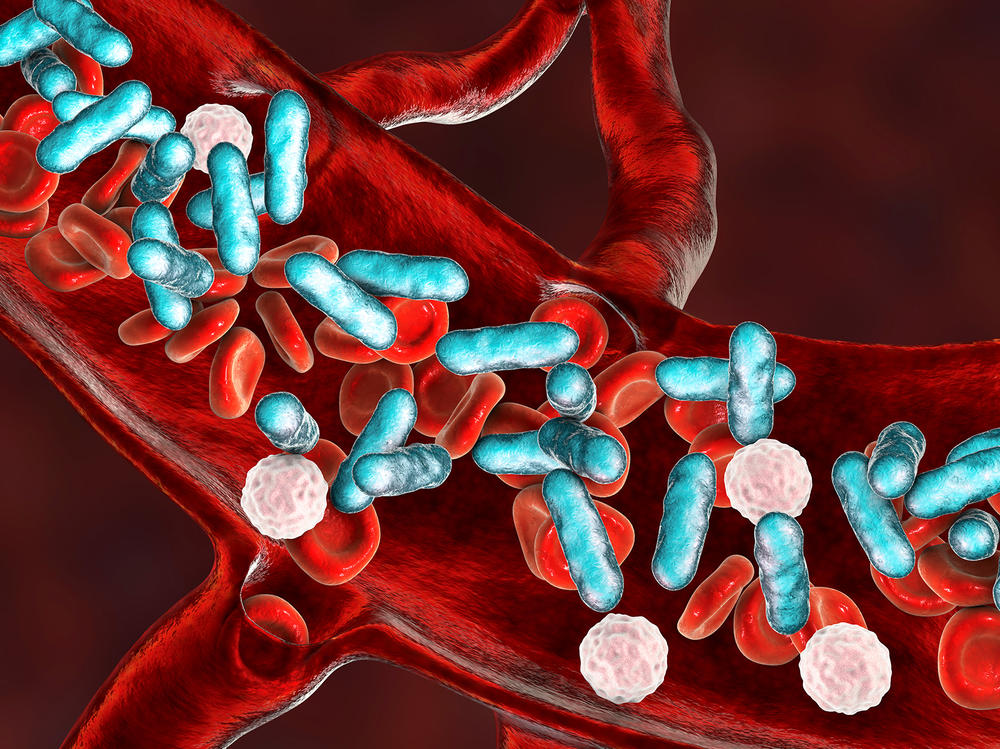

Sepsis, which is sometimes called blood poisoning, is essentially the body's overreaction to an infection. COVID-19 can trigger a similar reaction, known as a cytokine storm.

"Sepsis is one of the most common causes [of death] in the hospital, so finding a good treatment is extraordinarily important," says Dr. Jonathan Sevransky, a researcher and critical care physician at Emory University.

Sevransky, like dozens of other researchers, wanted to put the exciting observations from Norfolk to the test. So, he and a group of colleagues organized a large clinical trial. It ultimately recruited about 500 patients in 43 intensive-care units across the country.

But the treatment didn't help, Sevransky and colleagues report Tuesday in JAMA, the journal of the American Medical Association.

It was the largest, but not the first study to report disappointing results. Three other randomized trials have also been completed and "none of the trials showed a difference," he says.

Sevransky had originally hoped to recruit 2,000 patients for his study. But the Marcus Foundation, which bankrolled the research, decided to bail out after the trial had recruited 501 patients. An independent board privy to the results of the ongoing study had signaled that there was no clear answer as of that point.

If the treatment had matched the experience in Norfolk, Sevransky says, it would have been obvious by the time the study ended.

"We can say with some confidence that if there were such a large effect, we would have seen that in our patients," he says. But even a more modest effect could save many lives. Sepsis afflicts an estimated 1.7 million Americans a year, and 20% to 30% of people don't survive it. That's why Sevranksy had hoped to press on. One more large study is still underway in Canada, he says, and it could detect a smaller effect of the treatment, if it has any benefit at all.

The string of studies with negative results disappoints Dr. Paul Marik, who published those early dramatic claims. He's a critical care specialist at Eastern Virginia Medical School.

"Some people think the matter is dead," he says. "We would disagree."

Marik says his own more recent experience is that the treatment is only effective if given very early in the course of the disease. Marik says he now gives the infusions when people first show up in the emergency room, and doesn't wait for the hours or sometimes days it takes before someone ends up in the intensive care unit. And that's where researchers have studied this treatment.

"This should really be an emergency department study, not in ICU study," he says. "Once you've waited until they get to the ICU you've missed the boat."

Conducting research in the emergency department is a challenge because it's tricky to explain a study and to get permission in the midst of a health crisis. Marik says researchers in Belgium are trying to do that, though, with the regime he developed (which is sometimes called HAT therapy, based on the first letters of the technical names of its components, hydrocortisone, ascorbic acid and thiamine).

In the meantime, doctors who have been using this treatment face a decision. Should they keep offering it, given all these disappointing results?

That's similar to the questions they confront as they explore unproven treatments for COVID-19.

"What if the drug has no demonstrable treatment benefit but doesn't show any harm?" asks Dr. Christopher Seymour, a critical care specialist at the University of Pittsburgh. "Should we just give it with the hope that if the 'kitchen sink' is thrown at the patient there will be a benefit? I don't think so," he says, "in part because that distracts us from the science and the clinical care that might actually be making a difference."

At Emory, Sevranksy confronts conundrums this all the time with his COVID-19 patients.

"I can't tell you how many discussions I've had with patients and their families over the past year over how to decide whether or not to give something that's been touted in the news," he says.

In many ways, experimental COVID-19 treatments are a replay of the story of vitamin C, thiamine and steroids. Initial results suggest a strong benefit and enthusiastic doctors adopt the treatment, for lack of a better option. At the same time, many other doctors hold back and wait for more definitive results, knowing that often an idea that sounds great ends up falling flat.

And using an unproven treatment, even if it has very low risk, comes at a cost. It can consume precious staff time and resources. And it can also backfire.

"If you focus on something that might work, sometimes you can take your eye off the ball," Sevransky says, "and you don't focus on something you know works."

That's true in a pandemic, and true for the deadly disease of sepsis as well.

You can contact NPR Science Correspondent Richard Harris at rharris@npr.org.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.