Section Branding

Header Content

In The Pandemic's First Year, Three Huge Losses in One Family

Primary Content

In the year since the World Health Organization first declared a global pandemic, on March 11, 2020, millions of families have endured the excruciating rise and fall of the U.S. outbreak. The waves of sickness have left them with untold wounds, even as hospitalizations ebb and infections subside.

Some Americans have experienced tragedy upon tragedy, losing multiple family members to the virus in a matter of months.

For the Aldaco family of Phoenix, Ariz., it shattered a generation of men.

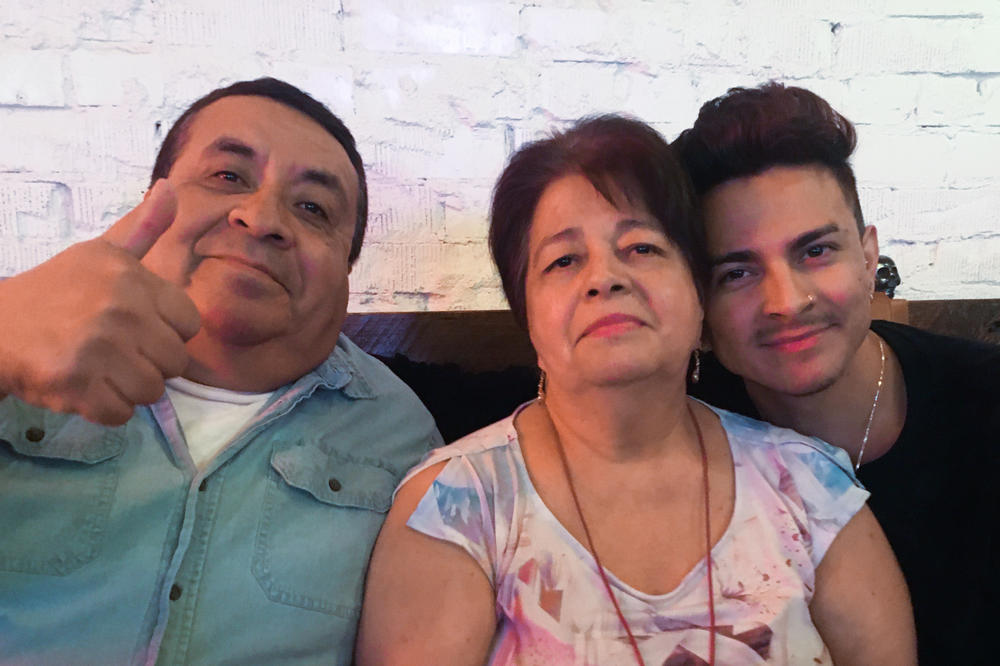

In just six months, three brothers — Jose, Heriberto Jr. and Gonzalo Aldaco — were lost to COVID-19, each at different moments in the pandemic: Jose died in July, Heriberto Jr. in December, and Gonzalo most recently, in February.

Their deaths are now among more than 530,000 in the United States, where, even as millions are vaccinated, the virus still leaves families grieving new deaths every day. The U.S. mortality from COVID-19 now averages around 1,400 deaths per day.

"Those three men, they drove the family, they were like the strong pillars, the bones of the family and now they're all gone," says Miguel Lerma, 31, whose grandfather Jose Aldaco raised him as his own son.

To Lerma, their deaths were the abrupt end to an epic American story of resilience, courage and hard work. All three brothers came to the U.S. as immigrants from Mexico and over the decades made this country home for their families.

"They literally showed that you can come from nothing and struggle through all that and still build a life for yourself and your kids," says Lerma. "It just upsets me this is the way their story has to end."

Jose's daughter Brenda Aldaco says with so many Americans gone, the magnitude of each death and its reverberations are profound.

"When you really think about each single person, each person individually, what did that person mean to someone? It's just overwhelming. It's overwhelming," she says.

Building an extended family always 'ready to create memories'

Jose Aldaco, 69, arrived in the Southwest in the early '80s when his daughter, Brenda, was still an infant, following his sister, Delia, and older brother, Gonzalo, who had both left Mexico not long before him.

"They came out here for a better opportunity — I don't even want to say a more comfortable life — but a more attainable, elevated life than what they had," says Priscilla Gomez, Jose's niece and the daughter of Delia.

Gomez thinks of all three uncles as central figures — symbols of strength — for her and the entire extended family.

"They were so consistent, the most consistent male figures for me," says Gomez.

Big family gatherings were a staple of life growing up in the Aldaco households.

"Those three men, when they were in the same room, it was just a good time," says Lerma, a dance teacher in Phoenix.

Reunions and holidays often evolved into joyous, music-filled events, where Gonzalo, the oldest, would pull out the guitar and the rest of the family would dance and sing together, into the early hours of the morning.

"If it was someone's birthday, they would sing 'Las Mañanitas' ... they were just always ready to create memories for us," recalls Priscilla Gomez.

Lerma says what Jose cultivated most of all was a family where love and affection was the main currency.

"He's the one who taught us to be so amorous," says Lerma. "He was that warmth. He was that love for us."

Intense waves of coronavirus swept Arizona

After a calm spring, the pandemic hit Arizona with terrifying force — the first of two waves that would rip through a state where officials were slow to adopt pandemic precautions, and quick to dismantle them. Lerma says his family heeded the rules and warnings.

"We were a family that accepted the pandemic was real," he says. "We did take it seriously."

Jose and his wife, Virginia, lived at their daughter Brenda's house, where they helped her out with the raising of their teenage grandson.

Jose worked a few days a week at his job in a hotel restaurant, but was mostly retired.

"He was perfectly able — doing yard work, cooking every day, jogging three times a week at the park," says Brenda.

Despite the family's effort to stay safe, the virus found a way into their household that summer. Jose was the first to get sick, but soon all four of them were ill and isolating in their bedrooms.

They waited on test results. Both grandparents were getting worse. When the bedroom door was open, Brenda's son could hear his grandfather.

"My son would say, 'Mom, Abuelo doesn't sound good... he sounds like he's dying," recalls Brenda.

She felt paralyzed, though. Her mother was adamant that she didn't want Jose to go to the hospital.

Eventually, Lerma, who lived separately and did not have COVID-19, put on a mask and came to coax his parents to go to the hospital. Lerma found Jose lying in the bed, covered in a sheet, with a sky-high fever.

"He was forcing fast breaths, to try to get any air that he could into his lungs," says Lerma. "That's when I started freaking out and losing it."

Both parents were admitted to the hospital.

A few days later, their mother was doing well enough to go home, but Jose's condition only got worse.

The last time Lerma saw him it was over Facetime, while Jose was being wheeled through the hospital to be put on life support. "Losing my dad, this is what heartbreak is," says Lerma. "This is what the sad songs are about."

Three brothers — 'totally devoted' to their families — gone

By the time of Jose's death, the virus had already killed about 150,000 Americans. Like so many families, the Aldacos were not able to have a proper funeral.

"It felt like his death was just brushed under the rug, like he's just another statistic," says Lerma.

Priscilla Gomez says she'll never forget hearing her mother take the phone call when she learned of her brother's death.

"To not be there in person, to comfort them or to hold them up when they feel like they just want to throw themselves on the ground and just sob... you feel completely helpless," she says.

As the pandemic stretched into the winter months, a new wave of infections and deaths gripped Arizona and much of the U.S. By late December, the total U.S death toll had surpassed 300,000, and Heriberto Aldaco Jr., the youngest in his late 50s, was now also hospitalized with COVID-19.

"You think you've gone to a particular point in your grieving and then it's not done, here it comes again.... now my dad's baby brother is sick," says Brenda Aldaco. "Then he passes away."

Less than two months later, yet more shattering news would come to the family.

The last remaining brother, Gonzalo Aldaco, the eldest of the three brothers, was hospitalized for COVID-19. He died in February.

Brenda Aldaco describes her father and uncles as above all else "family men."

"They were totally and completely devoted to the people they loved — always present, always someone you could rely on," she says.

Sometimes, she still expects her father to come home from the hospital: "It was just hard for me to even grasp the concept of 'He's gone'... that the three of them are now gone and under the same circumstances and within a period of six months."

This story comes from NPR's partnership with Kaiser Health News.

Copyright 2021 Kaiser Health News. To see more, visit Kaiser Health News.