Section Branding

Header Content

OPINION: 5 Ways To Make The Vaccine Rollout More Equitable

Primary Content

A key focus of President Biden's National Strategy for the COVID-19 Response and Pandemic Preparedness is to "protect those most at risk and advance equity, including across racial, ethnic and rural/urban lines."

The plan's vaccination strategy aims to produce and deliver safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines for the entire U.S. population. But the still-limited supply of these vaccines, along with impediments to vaccine access faced by some communities more than others, has given rise in recent months to ethical challenges.

While surges in new COVID-19 cases have hit a plateau in some regions, close to 1,000 Americans each day are still dying from this virus, with communities of color and especially those who are essential workers particularly hard-hit. As states expand their categories of who is eligible and prioritized to get the shot, everyone needs to grapple with questions of equity — how to improve vaccine access for all Americans, especially for groups historically made most vulnerable to severe illness.

Over the past year, the two of us — a public health ethicist (Faith E. Fletcher) and a physician trained in public health (Dr. Aletha Maybank) have regularly been asked by leaders in health care, politics, faith-based institutions and health advocacy groups to help guide discussions of social equity as it relates to COVID-19 testing, treatment and the vaccine rollout. Based on our experience, we have a few ideas about how this rollout process can be made more equitable throughout the country. In every case, it starts with respecting and deeply listening to the people most affected.

1. Recognize the barriers to equitable, quality health care

First some context: The ethical and equity questions raised by the pandemic are squarely rooted in the unjust living realities in many U.S. communities – both urban and rural — especially for Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander Americans. Members of these communities are at increased risk of getting severely sick and dying from a COVID-19 infection due to long-standing structural and social injustices – such as racism, sexism and class oppression.

For many people, a lack of internet access has contributed to the uneven uptake of COVID-19 vaccine. Plenty of stories highlight the challenges that individuals face trying to navigate the vaccine appointment system. That's particularly been a problem for people with limited time and resources.

In addition, many people don't have a reliable way to get to the health center or hospital. Having to drive two or three hours round-trip to see a doctor, or take two or three buses, can be a significant barrier to getting quality care. We especially see this problem in our work among communities burdened by health inequities and chronic conditions such as diabetes, kidney disease, heart disease, and HIV, for whom frequent and ongoing health care is particularly critical.

Difficulty in getting childcare, or elder care, or having long, inflexible work hours — experienced especially by essential workers in low-wage occupations — further diminish the opportunity for disadvantaged individuals to seek medical care, including vaccination appointments. All these barriers to COVID-19 vaccination are formidable, and delivering health care in a timely and efficient manner in such cases is especially important.

2. Acknowledge, respect and address concerns

So far, the Food and Drug Administration has authorized three safe and effective vaccines against the coronavirus for use throughout the U.S., with at least two more likely to be evaluated by the FDA soon. The Pfizer, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson vaccines all have been shown to be highly effective in preventing severe illness and death.

In particular, a vaccine like Johnson & Johnson's that has a long shelf life at regular refrigeration temperatures, and requires only one dose to achieve robust immunity — "one and done," as California's surgeon general, Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, described it when she got the shot — can help surmount some of the barriers to vaccination faced in underserved communities.

However, as we've seen with the initial rollout of the J&J vaccine, simply pronouncing a vaccine safe and effective isn't enough. It will also be crucial, as vaccination campaigns continue, for health care leaders and providers to acknowledge and address concerns raised by members of the public — especially in communities that have been socially and medically disenfranchised by unjust systems and policies — that they are being targeted with what some might consider a "less effective" or "inferior" vaccine.

Now is the time for public health officials to get the message and the messaging right. The good news is that health leaders don't have to figure out the messaging and strategies single-handedly. As the African proverb tells us "If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together." We can achieve vaccination equity nationwide through collective efforts, in consultation and partnership with various experts, community leaders and residents. We strongly recommend using these proven strategies that respect and meet people "where they are," in terms of their knowledge, values and location.

3. Empower choices with truth and transparency

Transparency is central to the field of bioethics and aligns closely with health equity efforts. In this case, it means clearly communicating the potential benefits and risks of scientific advances to promote informed decision-making.

Transparency between scientists and community members in scientific processes demonstrates respect for informed decision-making and acknowledges that individuals are capable of making moral judgements based on a commonly held notion of right and wrong.

4. Engage trusted community leaders

The need to engage a range of trusted community leaders to help fight the pandemic has been apparent from the beginning to many of us working in public health, as we watched the coronavirus — and confusion and misinformation about the virus — spread.

In response to structural racism and inequities in COVID-19 sickness and death among communities of color, many communities mobilized to engage these trusted messengers to deliver evidence-based COVID-19 vaccine information in tailored ways.

Leaders within the Navajo Nation, for example, despite having some of the most devastating rates of illness and death from COVID-19 in the country, have had tremendous success in their efforts to ensure vaccine equity — the vaccine has been made available to all community members. Unified and consistent communication from health care workers of not just the Indian Health Service, but other trusted voices, too, has been the key to the success. The Navajo Nation has higher vaccination rates than the rest of the country, with 26% having received one dose by the end of February. That's compared to a much lower vaccination rate among Black and Latinx individuals in the first month of the U.S. vaccine rollout — 5.4% and 11.5%, respectively.

We and colleagues have found in our work in the Black community that engaging interdisciplinary teams — including Black health care providers and public health professionals, faith-based leaders, barbers and hair stylists, leaders at Historically Black Colleges and Universities, the NAACP and community organizers who live, work, play and worship in these communities — can be invaluable in improving vaccination rates.

Door to door outreach, neighborhood town halls and Black doctors who staff 24-hour vaccination clinics have not only helped get vaccine into communities but have provided opportunities for listening to community members. That listening has revealed that the depiction of Black Americans as more vaccine-hesitant or distrustful than anyone else sorely needs reframing. If an individual is hesitant to trust, it's up to the health care system to prove its trustworthiness.

5. Enlist trusted messengers to create and deliver the message

To further help develop culturally responsive vaccination strategies and messaging in consultation with local communities, a national video campaign featuring W. Kamau Bell and a dozen or so Black doctors, scientists and nurses was recently launched to dispel misinformation in the Black community and provide accessible facts about COVID-19 vaccines. The goal is to ensure that every Black person in the U.S. has the credible information they need to make this critical choice.

"There are two major barriers to Black folks receiving the COVID-19 vaccines. Neither one of them are 'vaccine hesitancy,' " says Dr. Rhea Boyd, a pediatrician and public health advocate at the University of California, San Francisco and the Palo Alto Medical Foundation, who co-developed THE CONVERSATION: Between Us, About Us campaign. "The barriers are accessible facts about the COVID-19 vaccines and convenient access to receive a vaccine."

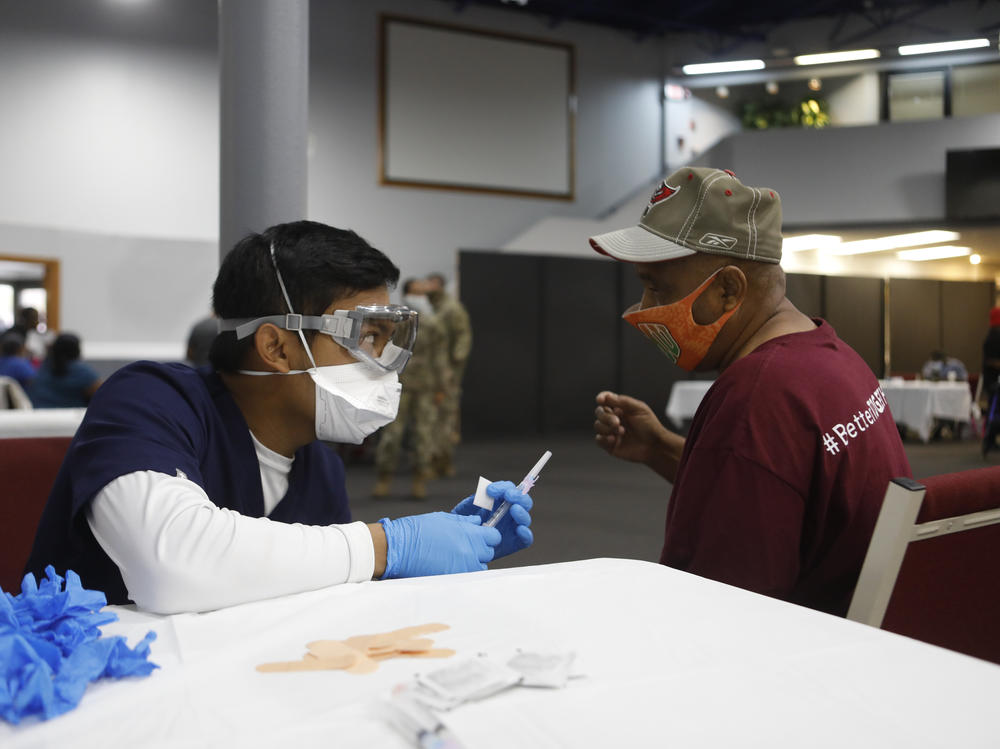

Dr. Ala Stanford, founder of the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium, is leading another effort — this time to expand equitable distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine to residents hardest hit by COVID-19 in areas of Southeastern Pennsylvania. She and colleagues have organized a vaccination and testing operation that eliminates scheduled appointments — and thereby eliminates the need for electronic sign-ups. By prioritizing zip codes to reach residents most in need of the vaccine, the group administered more than 25,000 shots to predominantly Black and brown residents in just 31 days.

In addition to administering Moderna and Pfizer shots, the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium is also giving the single-dose J& J vaccine — and educating communities about each vaccine, while respecting each individual's vaccine preferences.

Continual engagement of such trusted stakeholders and professionals will be integral to the success of mass vaccination efforts if we are to reach everyone. Oscar Londoño, the executive director of WeCount!, a membership-based organization for immigrant workers in Homestead, Fla., says translating credible educational materials about COVID-19 and COVID vaccines into not just Spanish, but also into the native Mayan indigenous languages that many people in his part of South Florida speak — and putting it on the radio in those languages — has been important in his community.

Community-centered vaccine efforts like all these show us that prioritizing the health needs, realities and preferences of traditionally underserved populations builds trust and trustworthiness in vaccine efforts. It also highlights that trusted professionals are instrumental in fostering vaccine acceptance to ensure that no community is left behind in vaccine distribution.

That's a lesson we are learning from this pandemic that must transcend it: Lifesaving advances in biomedicine can never achieve their full potential and achieve true health equity without engaging in equitable and ethical processes and practices that foster transparency and enhance the public's trust.

Faith E. Fletcher is an assistant professor in the Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy at Baylor College of Medicine and a senior advisor to the Hastings Center, a leading bioethics research institute. Dr. Aletha Maybank is the Chief Health Equity Officer and Group Vice President at the American Medical Association.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.