Section Branding

Header Content

In Missouri And Other States, Flawed Data Makes It Hard To Track Vaccine Equity

Primary Content

Throughout the COVID-19 vaccination effort, public health officials and politicians have insisted that providing shots equitably across racial and ethnic groups is a top priority.

But it's been left up to states to decide how to do that and to collect racial and ethnic data on vaccinated individuals, so they can track how well they're doing reaching all groups. The gaps and inconsistencies in the data have made it difficult to understand who's actually getting shots.

Just as an uneven approach to containing the coronavirus led to a greater toll for Black and Latino communities, the inconsistent data guiding vaccination efforts may be leaving the same groups out on vaccines, says Dr. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, an epidemiologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

"At the very least, we need the same uniform standards that every state is using, and every location that administers vaccine is using, so that we can have some comparisons and design better strategies to reach the populations we're trying to reach," Bibbins-Domingo says.

Now that the federal, state and local governments are easing mask requirements and ending other measures to stem the spread of the virus, efforts to boost vaccination rates in underserved communities are even more urgent.

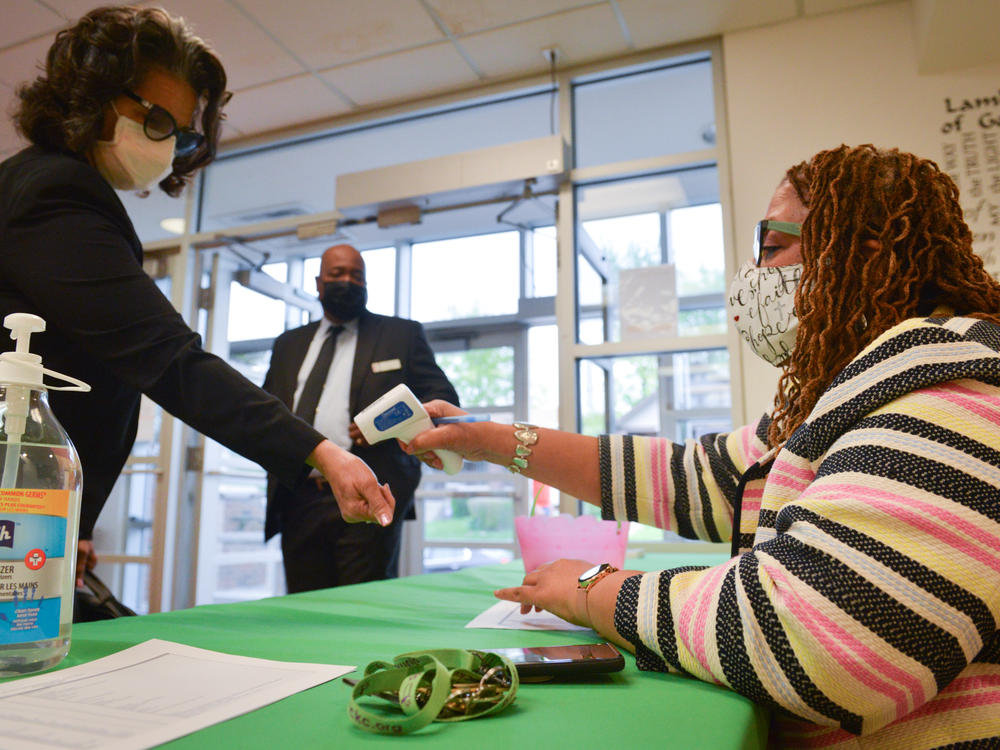

At St. James United Methodist Church, a cornerstone for many in the Black community in Kansas City, Mo., in-person services recently resumed after being online for more than a year. St. James has also been hosting vaccination events designed to reach people in the neighborhood.

"People are really grieving not only the loss of their loved ones, but the loss of a whole year, a loss of being lonely, a loss being at home, not being able to come to church. Not being able to go out into the community," says Yvette Richards, St. James' director of community connection.

Missouri's population is 11% African American, but COVID-19 cases among African Americans made up 25% of the total cases for the state, according to an analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Richards says that St. James has lost many congregants to the coronavirus, and the empty pews where they once sat on Sundays serve as stark reminders of all that this community has lost.

Missouri's public COVID-19 data appears to show robust data on the vaccination rates broken down by race and ethnicity.

The data currently show several groups lagging far behind on vaccinations, including African Americans, who appear to have a vaccination rate of just 17.6%, nearly half of the 33% rate for the state as a whole.

But to Dr. Rex Archer, director of the Kansas City, Mo., Health Department, one number is a giveaway that this data isn't right. It shows a completed vaccination rate of 64% for "multiracial" Missourians.

Such an exceptionally high rate for one group beggars belief, according to Archer.

"So there's some huge problem with the way the state is collecting race and ethnicity under COVID vaccination," Archer says.

Missouri state officials have admitted since February that this data is wrong, but they haven't managed to fix it or explain what's causing it. Archer believes the inflated multiracial rate is probably due to different racial data being reported when individuals receive first and second shots.

They've also found other data problems, too, including missing racial and ethnic data for many people who have been vaccinated, and the use of multiple categories such as "other" and "unknown."

The state also noted it used national racial percentages in the state's vaccination data rather than actual percentages based on the state's population. For example, earlier in the vaccination effort, the state used national racial data that shows nearly 6% of the population is Asian, even though Missouri's population is actually 2.2% Asian.

Health officials are now working to target vaccination campaigns in communities where rates are low, but Archer says the state's data provides little help.

"I mean, we have to look at it, but it's got too many variables to be something we can count on," Archer says.

Though racial and ethnic categories are clearly defined in national U.S. census data, the same data is not collected uniformly by states.

For example, South Carolina's vaccination data lumps together Asians, Native Americans and Pacific Islanders in one category. In Utah, residents can pick more than one race. Wyoming doesn't report racial or ethnic data for vaccinations at all.

Bibbins-Domingo, the epidemiologist, says that the missing or inconsistent data doesn't necessarily mean tracking equity is a lost cause. Vaccination rates for census tracts where racial and ethnic data is known can be used as a proxy to estimate vaccine allocations.

However, Bibbins-Domingo thinks the pandemic has shined a light on racial data problems that have persisted in U.S. public health for far too long.

"What my hope is, is that our lessons from COVID really cause all of us to think about the infrastructure we need within our state and nationally to make sure we are prepared next time," Bibbins-Domingo says. "Data is our friend."

Local leaders and health officials in Missouri are now scrambling to boost vaccination rates, especially among vulnerable communities, after Republican Gov. Mike Parson recently announced new steps to urge residents back to working in person.

Parson ordered state workers back to the office this week and said he would end additional federal pandemic-related benefits for unemployed workers in June despite vaccination rates across the state well below the percentages that health experts had hoped to achieve.

Jackson County, Mo., which includes most of Kansas City, authorized $5 million in federal CARES Act funding last week to increase vaccinations in six large Black ZIP codes in the urban core that have low vaccination rates.

The project will address problems of both access and hesitancy and focus on reaching out to individuals and neighborhoods.

While many of the state's vaccination efforts have involved large mass events, the Rev. Jackie McCall, a pastor at St. James, says that she's been talking with many in her church and community who need encouragement to have faith in the vaccines.

"So let's go ahead and let's trust," McCall tells congregants. "Let's trust the process. Let's trust God. Let's trust the science."

This story comes from NPR's health reporting partnership with KCUR and Kaiser Health News (KHN).

Copyright 2021 KCUR 89.3. To see more, visit KCUR 89.3.