Section Branding

Header Content

50 years ago, Nixon gave the U.S. a 'Christmas gift.' It launched the war on cancer

Primary Content

The roots of the National Cancer Act can be traced back to a small home in Watertown, Wisconsin, in the early 1900s.

A little girl named Mary tagged along when her mother went to that home, to visit their laundress, Mrs. Belter.

"My mother, on the way to visit her, said, 'Mrs. Belter has had cancer and her breasts have been removed,' and I said, 'What do you mean? Cut off?' And my mother said, 'Yes.' And I thought: this shouldn't happen to anybody."

When they arrived, Mrs. Belter was in bed with her seven children around her. She was terribly sick. At the time, Mary was quite young, around 4 years old. But she remembered that day for the rest of her life.

"When I stood in the room and saw this miserable sight with her children crowding around her, I was absolutely infuriated, indignant that this woman should suffer so and that there should be no help for her," she recalled decades later, in 1962.

"I was encouraged, however, by the fact that Mrs. Belter survived and she worked for many years later on for my mother, and I recall noticing that cancer didn't have to be fatal even though it was very cruel. And I'll never forget my anger at hearing about this disease that caused such suffering and mutilation and my thinking that something should be done about this."

That little girl grew up to be Mary Lasker, who transformed her outrage into action. Lasker became an activist, philanthropist and strategist focused on supporting medical research. She was also a prominent socialite, but one who never hesitated to use her influence among Washington's elite to push for better cancer research and care.

To fight cancer, you first have to talk about it

In the first half of the 20th century, cancer was misunderstood, if not an outright source of shame. It was widely considered a death sentence, and some even thought it was contagious.

"It was a disease diagnosis that was whispered about and kept secret," says Ned Sharpless, the current director of the National Cancer Institute. Sharpless says that to protect a person's dignity, doctors would commonly fib about someone's condition, or say, "'The patient died of old age.'"

Decades of advocacy — and scientific breakthroughs — have dramatically changed that. Today, cancer is no longer taboo, or ignored. The U.S. government has spent more money on the fight against cancer than on any other disease – and many cancers are now far less deadly than they once were.

A critical moment in this evolution was the passage of the National Cancer Act 50 years ago, on December 23rd 1971.

The makings of a cancer 'moonshot'

For years, Mrs. Belter's illness remained vivid in Mary Lasker's mind. Some 40 years later, in 1943, her cook also fell ill with cancer. As Lasker – a person with wealth and status – helped her employee navigate the medical system, she was shocked to discover that the field of cancer care had not advanced much.

So Lasker started a crusade. In the 1940s broadcasters wouldn't say the word "cancer" on the radio. She worked to change that, with the help of her husband, Albert Lasker, a major advertising executive. The couple convinced Reader's Digest to do a series of articles about cancer. And Lasker convinced her personal friend, advice columnist Ann Landers, to write about cancer.

But Lasker, who died in 1994 at the age of 93, didn't just focus on changing the popular perceptions of cancer. She wanted to cure cancer, and that demanded a real investment in medical research.

"The amount of money that's being spent for medical research is...well, it's just piddling," Lasker told Edward R. Murrow on CBS News, in 1959. "You won't believe this, but less is spent on cancer research than we spend on chewing gum."

She took over the organization that would later become the American Cancer Society, becoming chairwoman of the board and making research a top priority. She also turned her eye to Washington, convinced that only the federal government was big enough to commit the funds that were needed. After the United States put a man on the moon, Lasker started calling for "a moonshot for cancer."

"She understood that this was a big problem and the solutions needed to be big. But Mary was willing to think big," says Claire Pomeroy, president of The Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation.

Progress in treating childhood leukemia kindles hope

Lasker built her movement: lobbying Congress and making the most of her time on the social circuit. She was a frequent visitor at the White House, as a friend of President Lyndon Johnson and his wife Lady Bird.

At the same time, new treatments were being pioneered just a few miles away in Bethesda, Maryland, at the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Robert Mayer was working there, just beginning his career in medicine.

"Every Sunday night the planes would fly in with patients," recalls Mayer.

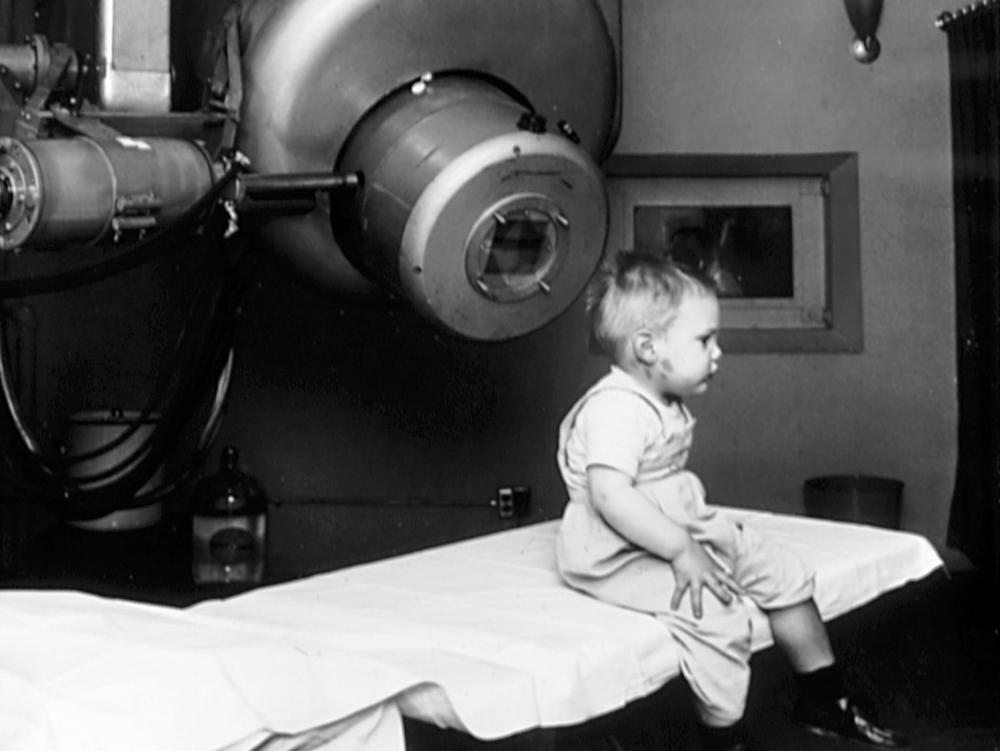

Those patients were actually young children with acute leukemia, traveling to the NIH to receive their monthly doses of chemotherapy. They came from all over the country, because at the time only a handful of hospitals were capable of aggressively treating cancer patients.

"My colleagues thought we were a little crazy that we would be giving people 'cell poisons' which is what chemotherapy was thought to be," says Mayer, now an oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and a professor at Harvard Medical School.

Chemotherapy was still experimental, but the doctors at the National Cancer Institute were getting results. For acute pediatric leukemia, the chance of survival went from virtually zero to about 50%.

"It wasn't just that they were people, they were children, and they were children at an adorable age of three or four or five," says Mayer.

As the stories of these surviving children trickled out in the 60s, a sense of optimism took hold.

"It really crystallized this moment that curing cancer through medical drugs was possible, the way we'd been able to cure infectious disease with antibiotics," says Sharpless, the NCI's director.

Next step: convincing Congress to go large

Cancer research was unlocking new possibilities, but Congress was tied up in a debate over how, exactly, to encourage more progress. A big sticking point was whether there should be a whole new federal agency – almost like NASA – to study cancer.

By the late 60s, Lasker felt things were moving too slowly, and decided on a new tactic: she took out targeted newspaper ads, in key Congressional districts, to increase the pressure on lawmakers.

"This absolutely shocked the people in the House because they never had ads before, and people were calling up from their districts and sending telegrams. And it caused quite a little commotion," Lasker said in one of her interviews for the Oral History Research Office at Columbia University Libraries.

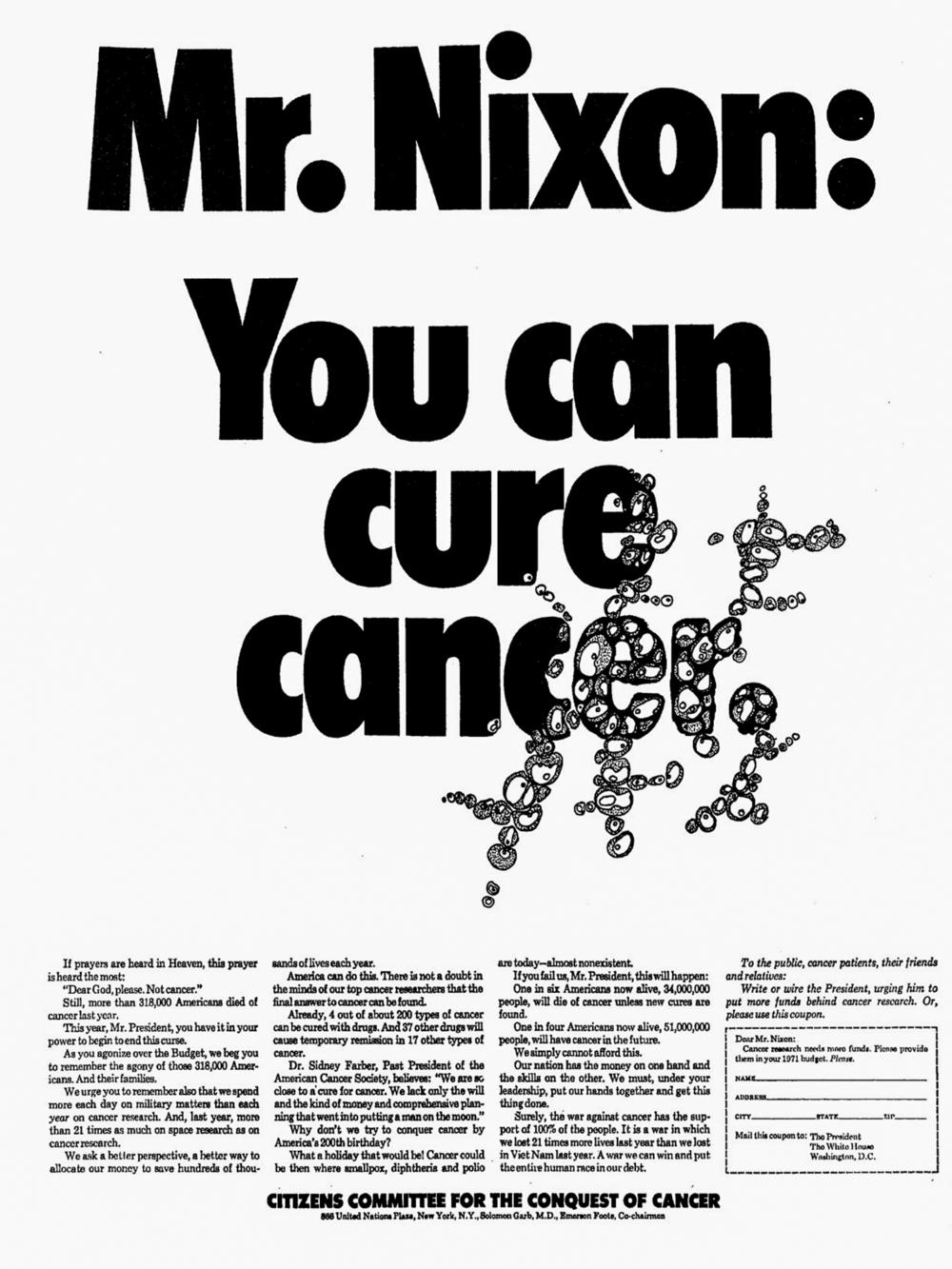

She also kept pestering President Nixon, and publicly. She paid for full-page ads in the New York Times and Washington Post. Big letters screamed out from the page: "Mr. Nixon, you can cure cancer." The small print at the bottom explained what was at stake:

"We spend more each day on military matters than each year on cancer research. And, last year, more than 21 times as much on space research as on cancer research... One in four Americans now alive, 51,000,000 people, will have cancer in the future. We simply cannot afford this."

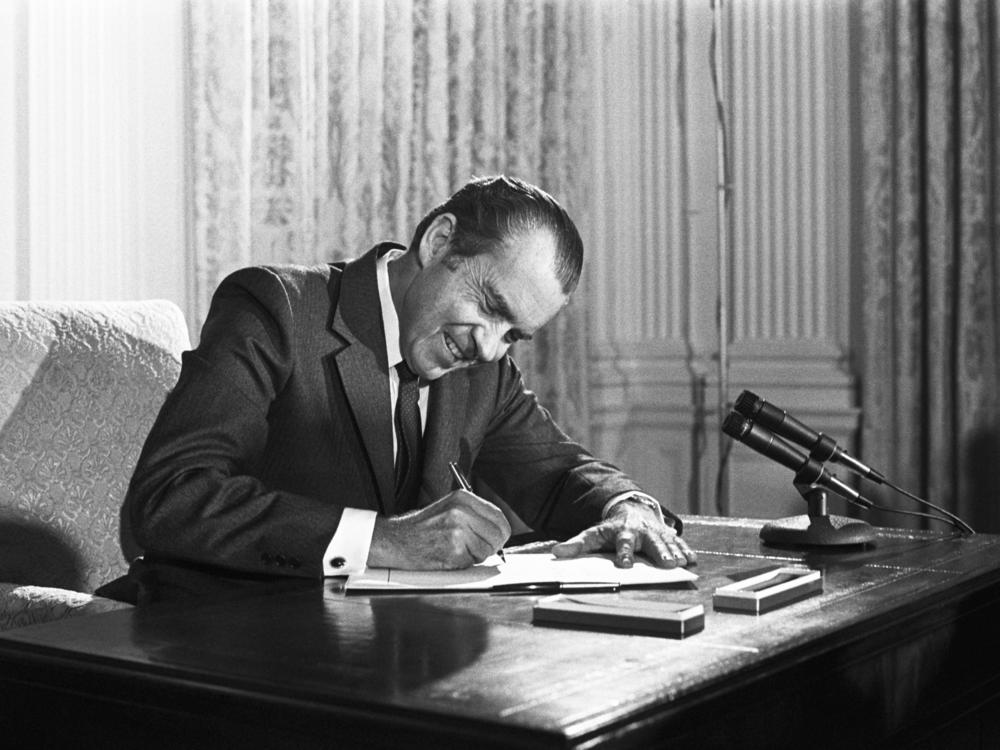

The decades-long campaign in research labs, in the halls of Congress, and in the media finally paid off. On December 23, 1971 – at about noon – President Richard Nixon walked triumphantly into the White House Dining Room.

'A Christmas gift to the American people'

Nixon rarely held a ceremony for signing a bill. And it was unclear, almost until the last moment, whether or not he'd sign the National Cancer Act publicly. But he did.

"For those who have cancer," he said, speaking to a crowd of well over 100 people, including Mary Lasker and a number of prominent scientists and politicians, "they at least can have the assurance that everything that can be done by government, everything that can be done by voluntary agencies in this great, powerful, rich country, now will be done."

Nixon sat down and took out the pen to sign the bill, calling it a "Christmas gift to the American people." Behind him, a row of smiling politicians. Over his shoulder, Senator Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts, the Democratic Majority Whip and chief sponsor of the bill in the Senate.

That moment reveals how support for medical research had become politicized, according to Robin Wolfe Scheffler, a historian of science at MIT. In Scheffler's analysis, Nixon signed the bill, in part, to ensure that his support for health research would not be in question during the upcoming 1972 presidential race. Kennedy was not seeking the nomination, officially, but was still widely considered a possible front-runner.

"Nixon embraces the War on Cancer as a way of taking an issue away from his potential future rivals, not necessarily because he has any particular desire to do something about cancer," says Scheffler, a professor at MIT and author of "A Contagious Cause: The American Hunt for Cancer Viruses and the Rise of Molecular Medicine."

Regardless of his motivation, the public investment was significant, $1.6 billion (almost $11 billion in today's dollars.)

"It's a substantial amount of money," says Scheffler. "If you consider, for example, last year, at the height of the COVID pandemic, the National Institutes of Health was given an additional $1 billion to look into COVID."

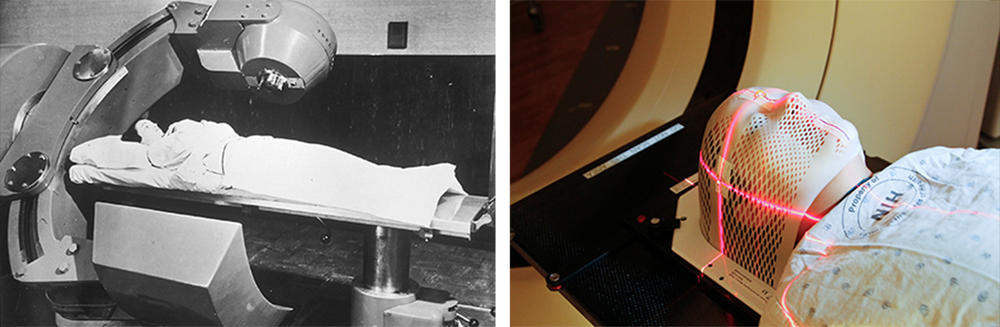

The National Cancer Act funded biomedical research, set up oncology training programs and built a nationwide network of cancer treatment centers.

At the signing, there were high hopes for what could be accomplished. President John F. Kennedy started talking about a moon landing in 1961, and that goal was achieved in less than a decade. Similarly, many thought the cancer moonshot would cure cancer in just five years, by the country's bicentennial in 1976.

But curing cancer would prove to be much harder than going to the moon.

"I think you have to admit two things about the National Cancer Act. On the one hand, it was visionary and transformative. It was one of the most important things the United States has ever done in terms of biomedical research," says Sharpless. "At the same time, we also have to admit that it was very naïve."

Impatience grows as cancer deaths climb

America's bicentennial came and went. Not only was there no cancer vaccine, but cancer death rates continued to climb. News anchors questioned whether the taxpayer's money was being wasted.

"People declared the War on Cancer 'a medical Vietnam,'" says Scheffler.

A debate ensued about whether the National Cancer Act's focus on basic research was misguided, if it wasn't leading to advances in treatment. Environmental activists also argued the emphasis should have been on prevention.

It took time for the research investment to pay off, Sharpless says.

"All this basic biology was bubbling beneath the surface. It doesn't look like much was happening in terms of cancer outcomes," he says, "But a lot was happening in the...cancer research space."

Now, 50 years after the funds started flowing, "we really are in a time of rapid progress," Sharpless says.

While 600,000 Americans still die from cancer each year, the overall death rate for cancer has gone down by about a third from its peak in 1991.

But the progress has been uneven.

One of the big discoveries that was made over the last 50 years, Sharpless explains, is that "cancer is not one disease or 10 diseases, it's hundreds of diseases or even thousands of diseases. And each one of these diseases is different."

For some of those diseases, the prognosis is still bleak. For example, the vast majority of people who are diagnosed with pancreatic cancer die within a few years. But for other types of cancer, there have been major medical advances. Death rates for colorectal cancer, cervical cancer and prostate cancer have declined more than 50%. And, there have been advances in the treatment of lung cancer, breast cancer and melanoma, among others.

"We have made remarkable progress," says Ahmedin Jemal, an epidemiologist at the American Cancer Society. "But there is a certain segment of the population that is not really benefiting from the advances that we have made in the past five decades."

There are still significant gaps in cancer death rates along racial, economic and geographic lines. And insurance makes a big difference—people with consistent health insurance are more likely to survive cancer than people who are uninsured or experience disruptions in health insurance coverage.

Jemal points to policies that can help reduce cancer death rates, including smoke-free workplace laws and tobacco excise taxes, as well as the 2014 expansion of Medicaid, which provides health insurance to the poor. Jemal points out that certain states in the South and Midwest that did not expand Medicaid were found to have slightly higher cancer death rates.

"We know that insurance is a major barrier to receipt of care, from primary prevention to early detection and, in the end, the treatment," Jemal says.

Advocates like Jemal say that the new goal going forward is to make sure that all Americans — no matter where you live, what race you are, or how much you earn — have access to 50 years of cancer progress.

This story comes from NPR's health reporting partnership with Kaiser Health News (KHN) and WBUR.

This story relied upon archived interviews with Mary Lasker conducted by the Oral History Research Office at Columbia University.

Copyright 2021 WBUR. To see more, visit WBUR.