Section Branding

Header Content

Britney Spears left her guardianship, but others who want independence remain stuck

Primary Content

Ten years ago, Nick Clouse was riding shotgun in his friend's Camaro in northern Indiana when the car jerked and he felt himself flying through the air. Clouse's head slammed against the passenger side window.

The traumatic brain injury caused severe memory loss, headaches and insomnia. Clouse, who was 18 at the time, didn't recognize his friends and family.

Shortly after the accident, his mother and stepfather petitioned to be his legal guardian, which meant they would be responsible for making all of his financial and health decisions. They said it would be temporary. A judge in Indiana made it official.

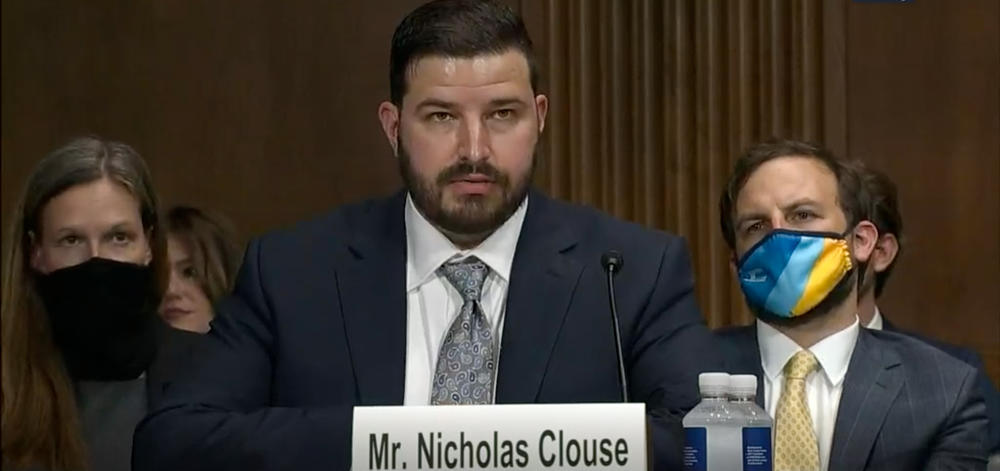

Years after recovering, Clouse wanted to make his own choices again — to put gas in his car, buy his daughter diapers and take his wife out for dinner without permission. But he ran into opposition. His parents didn't want to give up their power, Clouse said in testimony before the U.S. Senate, and he had to find a way to fight for his rights.

"They had 100% control over my life, and I just didn't have any say in what I did or anything," Clouse told NPR in an interview.

If a judge determines an adult is unable to make responsible choices, the person can be placed under a court-appointed guardianship. The arrangement is known as a conservatorship in some states.

It's a system that has come under scrutiny nationwide, after pop star Britney Spears sought to end her conservatorship. In September, in response to the Spears case, the U.S. Senate convened a committee hearing focused on the issue of guardianship reform. Clouse was invited to testify about his own experience.

Over time, Clouse testified, his traumatic brain injury improved. He started working as a welder, met his future wife — and got his parents' permission to marry her. Clouse wanted out of the guardianship, but he said his parents resisted.

In January 2021, Clouse and his lawyer filed a petition to end the guardianship. According to court documents, his parents insisted on a psychological evaluation of Clouse's decision-making ability. The evaluation determined guardianship was unnecessary and was dampening his ability to make independent decisions.

Eight months later, in August, Clouse's parents agreed to end the guardianship.

People like Clouse under a legal guardianship face a Catch-22. To regain his independence, Clouse needed to speak with a lawyer and get legal advice. That required money, but his parents controlled his finances. Clouse eventually found pro bono legal representation through the advocacy group Indiana Disability Rights.

The lawyer representing Clouse's mother and stepfather did not return multiple requests for comment.

A push to reform an inflexible system

In recent years, there has been a growing shift toward less restrictive options that allow adults with physical or intellectual impairments more independence while providing them support for making decisions. Advocates for people with disabilities say the shift is long overdue — and some argue the system needs a complete overhaul.

"People with significant disabilities have long been discriminated against, because people think that they [lack] the ability to make decisions," said Derek Nord, director of the Indiana Institute on Disability and Community.

While the disability rights movement in the U.S. has made huge strides on many issues, Nord said, additional reforms and better oversight are needed to protect people from exploitation.

Guardianship cases most often involve people with disabilities, the elderly, people recovering from an injury or a medical condition, and people with severe mental illness.

An official count does not exist, but the National Center for State Courts estimates about 1.3 million adults in the U.S. are in legal guardianships. In Indiana, where Clouse lives, 11,139 adults are in permanent guardianships, according to state officials.

In Indiana, entering a guardianship starts with filing a petition. The petitioner can submit evidence, like a doctor's report, and appear in front of a judge, who then decides if the person in question is considered to be incapacitated.

The judge can establish limitations for the guardianship — although they rarely do, said Indiana Disability Rights attorney Justin Schrock, who represented Clouse.

"We're talking about decisions about where to live, whether to get married, where to work, what medical care to receive, what to do with their money," Schrock said. "They really do lose all of their most fundamental basic rights."

Some guardianships are necessary, but advocates for reform argue they're overused; most of the time people with disabilities can make choices for themselves — sometimes with guidance — and should maintain that right.

"Before I entered this field, I assumed that [entering a] guardianship was a fairly innocuous step," Schrock said. "I also assumed that there were a lot of protections in place to prevent unnecessary guardianships from being established, which is absolutely not the case."

Legal guardianships should not be the default for people who need help making decisions, said Kristin Hamre, assistant professor of social work at Indiana University, Bloomington. It's in taking risks that people learn and grow as individuals — and restrictive legal arrangements like guardianships rob people of that opportunity.

"The right to risk is so important," Hamre said. "Risk is where life happens, right? You begin walking, you might fall; you begin driving, you might crash."

No easy way out of guardianship status

Because of the way some state laws are written, guardianship cases often lack due process, said Robert Dinerstein, head of the Disability Rights Law Clinic at American University in Washington, D.C.

Many states' guardianship laws ensure a right to legal counsel for people at risk of entering a guardianship. But that's not the case in Indiana. The law allows petitioners — often a parent or family member — the option to present a consent form signed by the person under consideration for a guardianship, which deems them "incapacitated" and effectively waives their right to contest the hearing or even be present at it.

Indiana's law also does not require petitioners to submit medical evidence to the court, although some courts have local rules requiring it.

"I've seen over and over again, these guardians' attorneys will have the individual sign this consent form, file it along with a petition, oftentimes with no medical evidence," Shrock said. "And some of these courts are just looking at that and saying, 'OK,' and then granting guardianship without ever having even laid eyes on this individual."

Since guardianship cases take place in county-level courts, there's tremendous variety in how these cases are handled. Larger counties with probate-specific courts can dedicate more time and resources to the hearings, while smaller county courts have a much larger breadth of cases, limiting a judge's expertise in one area.

A task force formed to examine the use of legal guardianships in Indiana reported that no medical evidence of incapacity was presented in 1 in 5 guardianship cases in Indiana. The 2012 report also states that in cases where evidence was presented, the reports were often incomplete or illegible.

The burden of proof — to convince the judge the guardianship is unnecessary — tends to fall on the person with a disability, which differs from most other legal proceedings, Dinerstein said.

People at risk of entering guardianships should have the same right to a lawyer as people in criminal cases do, Dinerstein argues.

"I think the level of loss of liberty [in guardianship cases] makes a really strong case that there ought to be" a right to legal counsel, he said.

It matters because once a person is in a guardianship, it is extremely difficult to get out of it. Dinerstein notes there are cases in which all parties agreed the guardianship should end, but it still took years to finalize.

"It's like Hotel California," Dinerstein said. "Once a guardian is appointed, even if circumstances change where you no longer think you need it, it's really hard to get courts to restore your capacity."

Clouse is now 28 and lives in Huntington, Ind. Shortly after his guardianship was terminated in August 2021, he took his wife and daughter out for dinner — a decision that no longer required his parents' approval. It was a small, but meaningful, luxury.

"I didn't have to worry about my card getting declined ... and bought my daughter a big piece of chocolate cake," Clouse said. "That made me feel good that I could just kind of splurge a little bit."

A growing call for less restrictive alternatives

In 2019, Indiana joined a handful of other states — including Delaware, Texas, Ohio and Wisconsin — in passing laws to require judges to consider less restrictive alternatives to guardianships.

Supported decision-making is one of these alternatives. Adults in these arrangements consult a support team, made up of friends, family, social workers, case managers or paid support members, about big decisions in their lives. But, unlike in a guardianship, the individual can still make the final decision.

"Many of us ... run important decisions by other people in our lives who are important to us — family, friends," Dinerstein said. "[Then] you get to decide whether to listen to the advice."

The year before the new law passed in Indiana, Jamie Beck became the first person in that state to transition from a legal guardianship into a supported decision-making arrangement — as part of a pilot program exploring less restrictive guardianship alternatives.

Beck has a mild intellectual and developmental disability and was placed in a guardianship at the age of 19 after her parents died. She spent a year in a nursing home, where she said she was bored and spent her time learning American Sign Language. Beck remained in the guardianship for eight years, even after demonstrating she could live independently and support herself financially.

"She was just doing tremendously ... and everyone felt she didn't need a guardianship any longer," said Judge Greg Horn, who terminated Beck's guardianship. "It wasn't like we were going to send her on her way and let her struggle with life's challenges."

To ensure she would be supported after the guardianship, the court worked with Beck to come up with a group of advisers she trusted to help her make decisions.

Beck said the supported decision-making agreement lets her have more say in her life. She's now 31 and lives in an apartment in Muncie, Ind. She works as a housekeeper at a local hospital and spends her free time playing Pokemon Go.

"I get to do more things like a typical normal person would," Beck said. She can seek medical care and travel out of town without needing anyone else to sign off on those decisions.

Despite new laws, enforcement lags

At least 11 states and the District of Columbia have passed laws allowing for supported decision-making.

In Ohio, lawmakers passed reforms to close loopholes in the guardianship system after a 2014 investigation by The Columbus Dispatch revealed lawyers were becoming guardians for people with disabilities and charging attorney's fees to perform basic duties, like shopping and cleaning. Today, the state requires guardians to undergo training and education and allows people under a guardianship to file complaints to the court.

But Kevin Truitt, legal advocacy director for Disability Rights Ohio, is skeptical that those reforms have led to major improvements for people with disabilities.

"Maybe some people have benefited from these reforms," Truitt said. "But I worry not a lot has changed for many, many people across the state" because people under guardianship may not be aware of the new law's provisions.

As part of the new law in Indiana, guardians are required to file reports every other year, documenting whether the guardianship remains necessary and whether less restrictive options have been considered.

The law also requires judges to document that less restrictive alternatives have been considered before full guardianships are approved.

But Schrock, the attorney with Indiana Disability Rights, said not much has changed on the ground, because of a lack of enforcement.

"I see ... guardianship petitions that are still filed today that don't even mention whether less restrictive alternatives have been assessed in any way," Shrock said. "And that has been ... a minimum requirement since July 1, 2019."

Schrock said that even when reports are filed by guardians, they are rarely scrutinized by judges.

State officials in Indiana say they're not tracking how many people are opting for supported decision-making agreements in lieu of legal guardianships. It's hard to determine because these agreements can take place outside of a courtroom.

Kim Dodson, CEO of the Arc of Indiana, said she has only heard of a few cases where people are looking to revoke a guardianship.

"That's not enough, right? We should have a lot more than that, especially two years after the implementation of supported decision-making," Dodson said.

Dodson thinks the COVID-19 pandemic slowed the education campaign around supported decision-making, so judges and backed-up courts are behind on implementing the changes.

But she's hopeful that over time, more people will understand the importance of ensuring people with disabilities are placed in the least restrictive arrangement possible.

"We really need to educate attorneys and judges, and make sure that they know about this new alternative, and that they get sold on it," Dodson said. "And that just hasn't happened to the extent that we've needed it to."

This year, in the Indiana legislature session, Dodson's organization will be advocating for additional guardianship reforms, such as requiring schools to educate parents of children with a disability on supported decision-making.

This story comes from Side Effects Public Media — a public health news initiative based at WFYI. Follow Carter on Twitter: @carter_barrett

Copyright 2022 Side Effects Public Media. To see more, visit Side Effects Public Media.

Bottom Content