Section Branding

Header Content

Inside an Oregon hospital, here's what it takes to provide care through the chaos

Primary Content

Nurse Heather Gatchet's shift in the emergency department at Salem Health's Salem Hospital typically starts at 6:00 a.m. Before that, she packs her daughter's lunch, drinks tea, and starts driving to work. To stave off her rising sense of panic, she calls her mom on the way.

"My mom's like my cup of coffee" Gatchet says, her voice breaking, "to mentally psych myself up for what I'm walking into."

Gatchet's mother reminds her that she's good at what she does, and that she's loved. She tells her "You got this, you've been doing this a long time."

When she arrives at work, Gatchet heads to the break room. Seeing her colleagues assemble for the day — the nurses in blue scrubs, the medical techs in teal — dispels any last bits of panic or dread: "This is my team, and it feels safe again."

More than 700 days have passed since the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Oregon. And yet Oregon, like the rest of the U.S., has seen far more cases in early 2022 than it did during any previous peak of the pandemic.

New cases have begun to recede, but the sheer volume of omicron infections continues to swamp hospitals nationwide. Salem Hospital, where Gatchet works, has been forced to adapt, yet again, to treat far more patients than it has licensed beds.

Dr. Peter Hakim works alongside Gatchet in the emergency department. Recently, his mother-in-law had a heart attack and was taken to a small, rural hospital elsewhere in Oregon. She needed specialty care that wasn't available there.

"They could not find a bed for her anywhere in Washington or Oregon for 24 hours," Hakim says. "So she was sitting in this small six-bed emergency department and couldn't get transferred out."

Hakim called a supervisor and tried to get his mother-in-law transferred. There wasn't any space.

"At that point, I think our hospital capacity was about 115%. And we had 40 people waiting in our emergency department for beds upstairs," he recalls.

"It made me feel a little bit helpless. But it was one of those times I was at work and I still had to find a way to compartmentalize those feelings, and care for the people that were here, because the people that are here are somebody else's family."

His mother-in-law eventually got the specialty care she needed. But Hakim says that during this omicron surge, a lot of people "are not as lucky."

"Just figure it out each day."

Salem Health's emergency department has 100 beds. To handle the influx of people seeking treatment, hospital staff put dozens of wheeled gurneys in the halls.

By noon, patients start to occupy those temporary beds in the hallways. The emergency waiting room is full of patients, and ambulances keep pulling up to the ambulance bay out back – seven, eight, nine at a time.

The pressure builds through the afternoon as more and more patients arrive. By the evening, the entire hospital is full, and the hallway beds in the emergency department are the only place left for new patients to go.

It becomes harder and harder for Gatchet to concentrate on treating the person in front of her, amid the overwhelming noise of all the other patients.

"They're crying because they're in pain, or they're screaming because they're having a psychiatric crisis, or we've put an alarm on them to alert us if they're trying to climb off the gurney for safety reasons," she says.

Three years ago, treating people in the hallways would have been an extraordinary measure. Now Gatchet and Hakim prepare for it every day.

Some of what Hakim must do, like cutting off clothing to examine a broken hip, is too sensitive for the hallway.

Two weeks ago, Hakim had to evaluate a seriously ill patient in the bathroom.

"I have to see what's going on," he says. "And that is the one private space we could find at the time."

A fragile system stretched beyond capacity

The Salem Health Salem Hospital has been above 100% capacity for months, with patients doubled up — and even occasionally tripled up — in their rooms, according to hospital executives. Salem Health allowed a reporter to shadow Gatchet and other staff members on Jan. 27, a date that proved to be the hospital's highest yet census of COVID-19 patients —122 people, nearly 1 out of every 4 patients in the hospital, had the virus.

About 70% of that COVID-19 tally consisted of patients admitted with respiratory symptoms, according to hospital executives. The other 30% were asymptomatic cases discovered upon admission.

But those 122 patients are just one part of the immense strain the pandemic has put on this hospital.

If you picture the health system as a line of dominoes, emergency medicine is at one end. But the domino that tipped over first, sending ripples of chaos through the entire system, is the one that represents long-term care: the nursing homes and rehabilitation facilities.

Statewide, more than 70% of long-term care facilities in Oregon experienced one or more COVID-19 cases in January, among residents or staff. Many reported full-blown outbreaks.

The caregivers who work in nursing homes and other residential facilities are among the lowest-paid in healthcare. Many are burned out, and they're quitting the long-term care sector in record numbers. Like other companies, long-term care employers must compete for workers in a crunched labor market.

The outbreaks, and the staffing shortages, mean that hospitals can't discharge patients to nursing homes. Those facilities are closed to new admissions.

It's also harder to find help for patients who could be discharged to their homes, but need assistance after a severe illness or disabling accident. In-home caregivers and even equipment like wheelchairs are scarce.

Dr. Sarah Webber is a hospitalist at Salem Health, which means part of her job is figuring out where patients should go after discharge, and what kind of supportive care they will need. Prior to the pandemic, coming up with a safe discharge plan for patients typically took her team a few days, she says.

"Now sometimes it is taking a week or two. And I do have some patients that have been here for several weeks."

At one point she was caring for 20 inpatients, but eight of those were stable and ready to leave — but they didn't have a discharge plan.

Webber says people generally think of hospitals as safe places, but lengthy or unnecessary stays also come with real risks.

The longer a patient stays, she says, the greater the chance of infections, pneumonias, and becoming bedridden.

"It delays and potentially decreases a patient's ability to become independent again," she explains.

Statewide, almost 600 patients are ready to leave Oregon hospitals, but are waiting on a discharge plan. They now account for one in 10 hospitalized patients.

The situation has given rise to a vicious cycle: when these elderly or frail patients don't receive the recommended rehab or supportive services they need to get stronger, they often wind up back in the emergency department, where there's little that a physician like Dr. Hakim can do for them.

"What they need is just somebody to stop by once or twice a day at their home to help," Hakim says.

Treating COVID patients, feeling both sadness and hope

The doctors and nurses at Salem Health have seen this pattern before, during the delta wave: the majority of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 haven't been vaccinated.

"There was a potential way to prevent it," Dr. Webber says. "It's really hard to over and over and over again feel helpless, like we had an answer, but people chose not to take it. And then they want me to fix it, and I can't."

But compared to delta patients, patients infected with the omicron variant are, on the whole, requiring less supplementary oxygen and less intensive care.

"I'm seeing more patients live," says Jackie Williams, a respiratory therapist who works on every floor of the hospital. "It's like a little glimmer of hope."

In the intensive care unit, there were only eight COVID-19 patients. There was just one ICU bed still available.

The hospital has developed a contingency plan, should the situation get worse: the staff will double up patients in the ICU.

But the hospital managers are relatively confident they won't need to take that step.

Many of the COVID-19 patients at Salem are in less critical condition, and are being treated in the hospital's medical-surgical unit, in rooms with closed doors. The nurses give the patients oxygen with nose cannulas, turn them every two hours to prevent bedsores, and roll them onto their stomachs to help keep their lungs open.

But there are so many of them that the workload is heavy for the staff. For the patients themselves, being hospitalized with covid-19 can be isolating, frightening, and lonely.

In the hallway outside rooms full of COVID patients, a nurse manager is talking with the wife of a newly-arrived COVID patient, just transferred upstairs from the emergency department.

The nurse manager explains to the wife that she can't go into his room, and she actually needs to leave the hospital. That's because she was exposed to the virus while caring for her husband and she could potentially infect hospital staff or other patients. The wife quietly fights back tears as she hands the nurse a bag with her husband's glasses and a clean change of clothes.

"Does he have a cell phone?" the nurse manager asks, "The nurses, they can help him do FaceTime so you can talk to him, okay?"

The nurse manager adds: "I'm sorry."

A member of the Oregon National Guard passes by with a supply cart, and calls out a greeting. Gov. Kate Brown deployed hundreds of them in January to help with staffing shortages.

The guard members help with supplies and logistics, providing some relief — and moral support — to staff members who feel ground down.

Their exhaustion can be physical, mental, and even emotional. For Dr. Sarah Webber, it stings that many of her patients still decline her advice to get vaccinated after they recover.

"People come to the hospital sick and they want me to help them, but they won't trust me over the basics of how to help them or how to prevent it," she explains.

At home, she finds she has less patience with her children — and they seem to need her more.

Her six-year-old daughter recently asked why Webber couldn't just stay home with her.

"She asked me, 'Are the sick people more important than me?'" Webber says.

"I told her 'Of course not, they're not more important' and that I love her... but that those people also need me."

In just the last few days, hospitalizations in Oregon appear to have reached their peak — and are plateauing. The hope is that as the omicron wave subsides, the pressure inside the hospital will ease up a little bit.

But they also suspect that other health issues will resurface, and that some problems have gotten even worse during the the pandemic

"It might not be breathing problems, but it's alcoholism. It's suicide. It's traumas," said Jackie Williams, the respiratory therapist. "It's all these other things that are what the world is dealing with, after coming out of two years of a pandemic. And those are critical illnesses too."

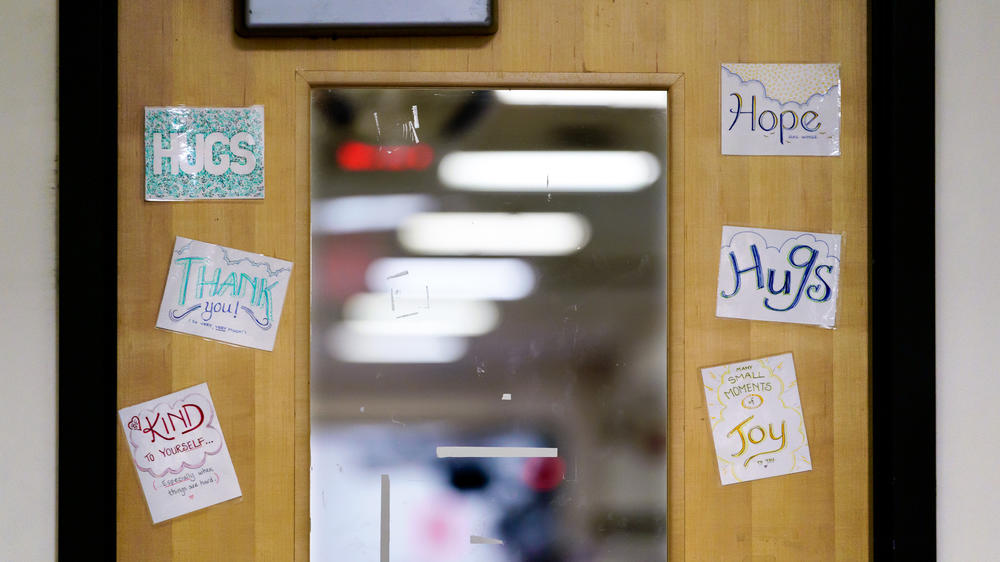

In the emergency department, Heather Gatchet does what she can to comfort her patients, stuck for hours in a place where the lights never turn off. They can't see her smile underneath the mask, so sometimes she holds their hands.

"If I can help control their anxiety a little bit, maybe I can control my own energy and get through," she explains.

At 6:00 pm, her 12-hour shift ends. She clocks out, gets in the car, and sings her heart out on the short drive home.

This story comes from NPR's health reporting partnership with Oregon Public Broadcasting and KHN.

Copyright 2022 Oregon Public Broadcasting. To see more, visit Oregon Public Broadcasting.