Section Branding

Header Content

Stone Age brain surgery? It might have been more survivable than you think

Primary Content

Did Stone Age people conduct brain surgery? Medical historian Ira Rutkow points to evidence that suggests they did.

"There have been many instances of skulls that have been found dating back to Neolithic times that have grooves in them where portions of the skull have been removed. And it's evident if you look at these skulls, that this was all done by hand," Rutkow says.

There's no written record of Stone Age neurosurgery, but Rutkow theorizes it may have been conducted by a shaman on patients who were comatose or who had been otherwise injured. What's more, he says, physical evidence indicates that some patients likely survived: "With many of these older skulls, new bone growth had already formed, and bone in the skull can only form if the patient is alive," he says.

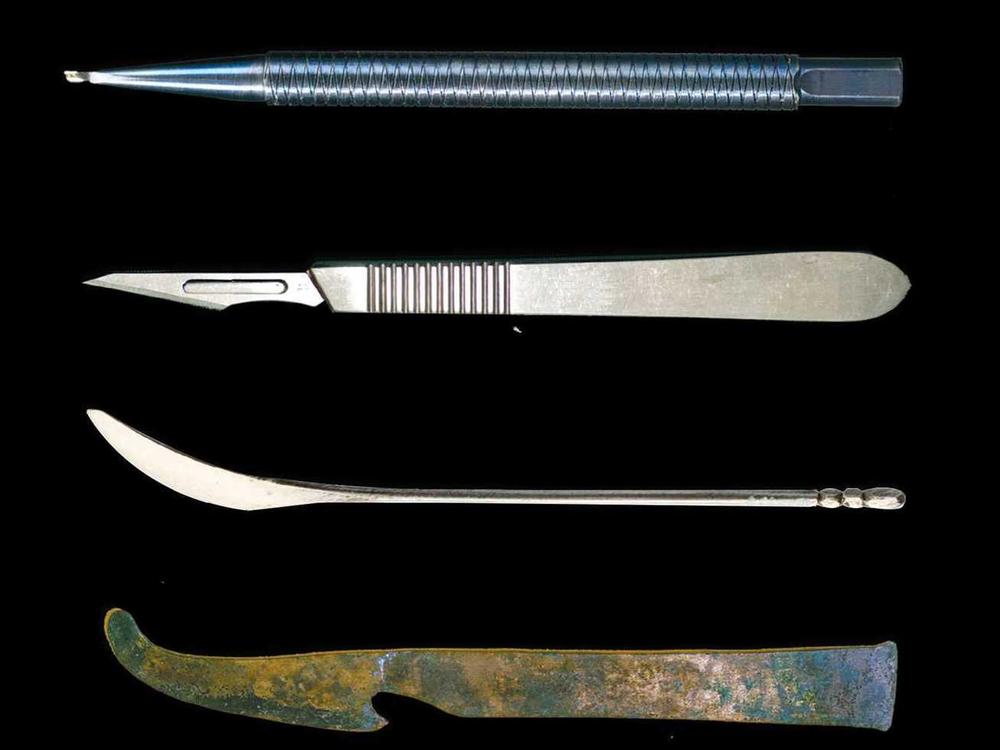

Rutkow is a surgeon himself. His new book, Empire of the Scalpel, traces the history of surgery, from the days when barbers did most operations and patients died in great numbers, to today's high tech operations that use robots with artificial intelligence.

He says that when looking back, it's important to keep in mind the body of knowledge that existed at a particular point in history — and to not judge surgeons of yore too harshly.

"People write about medical history and they say, 'Oh, it was barbaric,' or 'The doctors were maltreating,'" he says. "We have to remember at all times that whatever I write about in the past was considered state of the art at the time. ... I would hate to think that 200 years from now, somebody is looking at what we are doing today and saying, 'Boy, that treatment that they were doing was just barbaric. How do they do that to people?'"

Interview highlights

On the four main obstacles for modern surgery

To do an effective and safe surgical operation, there are four elements that are more important than anything else, more important than the mechanistic things that you need to do an operation. And these are an understanding of human anatomy. A surgeon needs a road map. They need to know where things are located. Second thing is how to control bleeding. If there's bleeding going on during an operation, that road map, that roadway gets flooded and the surgeon can't see anything. Third is anesthesia. They had to figure out how to reduce pain on patients. And the fourth is antisepsis. So these four elements — anatomy, bleeding, anesthesia and antisepsis — had to be discovered. They had to be improvised and they had to be worked on.

The four elements, once they came in, were very, very important. But we've undergone a major transformation in surgery in the last 20 to 25 years, meaning ambulatory surgery, where you go home literally hours after the operation, [and] many operations through small incisions and laparoscopic repair, where it's through tubes that they put inside and the surgeon can see with a camera. This is a major revolution and transformation in surgery as large as anything else that's happened in the past.

On surgeon being a low status job in ancient societies

Back in ancient times in Rome and in Greece, in the Middle East with Hammurabi, surgeons were always looked down upon. The priests/physicians were considered the educated elite at the time, and they looked down upon anybody who worked with their hands. Now, of course, what you and I would consider to be surgeons, they were the ones working with their hands: cutting out a boil or removing a bunion. That was what surgery was all about. But there was this very demeaning attitude toward individuals who did manual operations, who worked with their hands. And what happened over the course of time, this demeaning attitude would change. It would not change, however, until the 20th century.

On how the Church influenced surgery in the Middle Ages

The Church really started taking over the care of individuals beginning in the Middle Ages. And what happened was that the monks within the monasteries at the time would render care. When we talk about care, we're thinking of the 21st century, and what we have was nothing like that back then. But the monks were around and they provided whatever care they were able to to individuals. At the same time, there were men, mostly men, who worked with the monks. They were called the barbers. They shaved the monks. They cut their hair. And over the course of time, these barbers were able to do more and more surgery. Now, surgery, of course, was cutting out a bunion or lancing a boil or perhaps doing an amputation of a mangled finger. It's not surgery, as you and I know it today.

They handled the scalpels that existed at the time. The barber/surgeons were the ones who allowed surgery to continue and advance. They were not educated. They passed their traditions and their skills within the family, from son to son, father to son. And this continued for hundreds of years, really, up through the Renaissance, up until the 16th century.

On bloodletting

They would incise a vein and they would allow blood to drip out and they would collect it. And they collected enormous amounts of blood from individuals. We're talking about literally tens of ounces, ten, 20, 30, 40 ounces at a time. The endpoint of bloodletting for many individuals was to faint. So how did all this start? In ancient Greece, there was a theory that all of human disease developed around what they called four humors: yellow bile, black bile, phlegm and blood. And they felt that these humors needed to be in balance for there to be no disease. And amongst their ideas was that blood needed to be taken out of the body. And so bloodletting developed in Greece. And, in fact, bloodletting continued almost up to around the beginnings of the 20th century.

On President James Garfield dying in 1881 after a gunshot wound became infected (by his own doctors)

The doctors come on horseback. They come riding carts. The carts have reins that the horses are wrapped up in, and the reins are on the ground, as they've been for thousands of years. The ground is filled with horse manure and other bacteria. The doctors don't know any better. They pick up the reins. They have manure-covered hands. They go in to see Garfield. The first doctor takes his finger and puts it down the hole where the bullet went and starts to feel it to see if he can feel the bullet. Now, of course, in doing that, he's introducing bacteria, overwhelming numbers of bacteria, into Garfield's wound. He never washed his hands. So this went on for about 80 days with doctors coming in and examining Garfield. The older surgeons would not wash their hands. Garfield develops these huge abscesses throughout his body and eventually succumbs to sepsis, to an infection, as you would expect.

On advancements in robotic surgery

Robotic surgery is increasing in its sophistication and its ability to do operations. Right now, robotics are used because they're so precise in their movements that they're able to get into crevices and corners and other areas that a human hand might not be able to go into. Now, understand that currently the robots are still controlled at a certain level by human beings. They're sitting there at the monitors looking at what's going on. Somebody has to control the robot because if something goes bad, they need to be able to take care of the situation without the robot. Although I read the other day how at Johns Hopkins, my alma mater, they had just invented or were working on a surgical robot that would not need to have any human input. So we're clearly progressing towards that type of outcome, where you're going to have robots that are programmed using AI, artificial intelligence, who are able to do these operations by themselves. Now, is that scary? Yes. Will it work? I suspect that it will work.

Lauren Krenzel and Joel Wolfram produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Laurel Dalrymple adapted it for the web.

Copyright 2022 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.

Bottom Content