Section Branding

Header Content

As home births rise in popularity, some midwives operate in a legal gray area

Primary Content

Mandy King laid back on a large, brown couch at Shiphrah Birth Services in Vinton, Iowa, as soft piano music streamed from a TV in the background. Her three young children — ages 3, 5 and 7 — played next to her as her midwife, Bethany Gates, examined her pregnant belly, applying pressure with her hands on different parts to identify the baby's position.

On this early spring day, King was 38 weeks pregnant.

"Her head's not really moving a lot," Gates said. "She's kind of settling into the pelvis a little bit, but that's good. That's what we want her to do."

King is planning her first home birth. As a self-described homebody, King said she disliked giving birth at a hospital, away from the comfort of her home and children.

"The experience of being at home is going to be amazing for my mental health," she said. "[In previous births] there was just a lot of crying, a lot of 'I miss my other kiddos. I want to be together as a family.' So I'm really excited for that aspect."

King said she found Gates through a Facebook group.

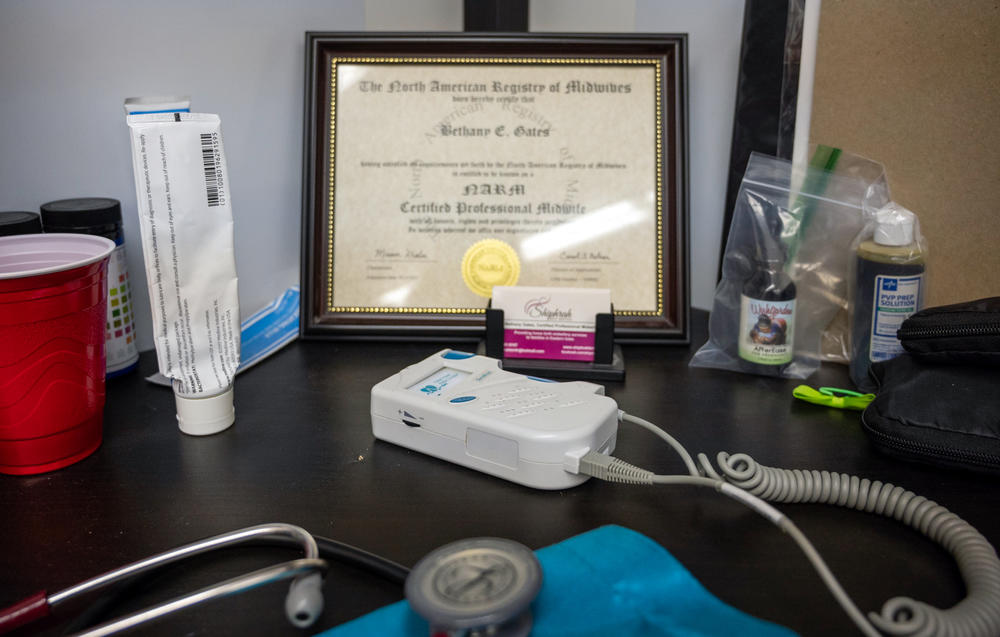

Gates is one of about 12 certified professional midwives in Iowa. These are non-nurse midwives who specialize in home births and are certified through programs approved by the North American Registry of Midwives.

Iowa is one of more than a dozen states where midwives like Gates operate in a legal gray area. Current legislation is in the works to change that by creating a licensure board for certified professional midwives.

More people — like King — are choosing to give birth at home instead of in a hospital in recent years. In 2019-20, the number of home births in the U.S. rose 22% — to more than 40,000. Home births now make up 1.3% of all births in the U.S., following a steady rise since 2004, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The increase in home births comes as obstetric facilities in rural America continue to shutter. In Iowa, eight hospitals closed their labor and delivery units in 2020-21, according to data from the state's Department of Public Health.

Midwives like Gates say gaining licensure in Iowa would help to address the growing demand for home births and address the growing maternity care deserts. But home birth advocates and hospital administrators are at odds about the issue.

High demand, little oversight

Gates has overseen about 100 home births over the past five years. She said prior to the pandemic, she never had to turn away clients due to high demand. But last year, she said requests for her center's home birth services surged.

"We had, like, 120 inquiries from prospective clients, and we were not even able to take half of them," Gates said.

Following nationwide trends, home births in Iowa increased more than 30% in recent years — from 512 in 2019 to 674 in 2021, according to state health data.

Gates said unlike nurse midwives who work primarily in hospitals, certified professional midwives like herself focus on home births for low-risk pregnancies.

"We are the experts in out-of-hospital, normal, low-risk birth," Gates said. "We get to know normal really well, so that anytime anything moves outside of that normal, we know it's time to bring in someone else with a different skill set."

Fifteen states, including Iowa, Nebraska and Kansas, don't license certified professional midwives. Gates said without licensure, midwives are unable to obtain the medications and lab tests they need to practice.

"I'm not illegal to practice, because there is no state law prohibiting my practice," she said. "However, there's also no law saying I can, and that is where we get into the issue of midwives being charged."

This is driving skilled midwives underground, she said, and even out of unlicensed states like Iowa.

At a recent legislative hearing, Melanie Peterson, a certified professional midwife who has worked in Iowa for more than 30 years, said she was charged in 2006 for practicing medicine without a license.

Peterson said she took a plea agreement, and the charge was expunged from her record.

"I've done hundreds of births, specifically in Cedar County, where there are no gynecological, no obstetrics, no hospitals," she said. "So it's rural women who are having home births. They have no access to care out there."

The need for labor and delivery services in some parts of the U.S. is greater than ever. Nationwide, between 2004 and 2014, nearly 1 in 10 rural counties experienced the loss of all hospital obstetric services — and another 45% of rural U.S. counties had no hospital obstetric services at all, according to a 2017 study published in the journal Health Affairs.

"We're not going to make OB units open, but we're going to be extra manpower to help," Gates said. "If an OB unit closes in a county where there's a midwife, that midwife's automatically going to be a lot busier. So licensure allows more midwives to come into the state to help fill that void."

Disagreement on the path to licensure

In early March, Iowa lawmakers echoed Gates' sentiment when the Iowa House passed a bill that would establish a licensing board for midwives. It received bipartisan support.

"It's that rural access to health care that so many young families need," said Rep. Mary Mascher, a Democrat from Iowa City. "And one of the most important parts of this bill is the fact that we've had so many birthing centers close in hospitals across the state, and so this opens up access for them."

If this measure passes, Iowa would join 35 other states, plus Washington, D.C., that have already passed legislation licensing certified professional midwives.

But the state's major hospitals and health care providers have objected to the bill, saying it doesn't require strong enough transfer agreements and coordination between midwives and hospitals. They argue that this could result in medical liability issues for hospitals and poor outcomes for moms and babies.

"We're setting up a scenario here where, if there is a complication occurring, we're going to be dropping women in the emergency department with no warm handoff, and that is not a scenario that we are comfortable with," said Dennis Tibben, a lobbyist for the Iowa Medical Association, at an Iowa Senate subcommittee hearing in March. "We believe that that is a very dangerous situation."

Professional organizations like the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, or ACOG, have a more nuanced view.

Lindsey Jenkins, an OB-GYN in Des Moines and the Iowa legislative chair for the ACOG, said the organization would like to see the bill restrict midwives' scope of practice to carefully defined low-risk pregnancies before supporting it.

"The problem with obstetrics is everything goes really well until all of a sudden it doesn't," Jenkins said.

A hospital or accredited birth center is always the safest place to give birth, she said. But if a woman wants to have a home birth, it should be carefully planned with a trained professional.

"It's having a midwife who has met the minimum required standards of training to be able to provide care in and out of hospital birth. Somebody who's willing to accept limitations on their scope of practice," she said.

ACOG's latest statement on birth settings, published in 2020, cautions against home birth, stating that while planned home birth is associated with fewer maternal interventions than planned hospital birth, "it also is associated with a more than twofold increased risk of perinatal death (1–2 in 1,000) and a threefold increased risk of neonatal seizures or serious neurologic dysfunction (0.4–0.6 in 1,000)."

Research suggests that limiting planned home birth to low-risk individuals could make it a safer option. A 2021 peer-reviewed study in ACOG's journal, Obstetrics & Gynecology, found low-risk mothers with planned home births had a low rate of adverse outcomes in Washington state, which has a well-established practice of community midwifery.

Compromise on licensure can be difficult

To address hospitals and health providers' concerns, some states, such as Indiana, have put additional restrictions on midwives. Indiana passed its licensure legislation in 2013, and has 17 actively licensed certified professional midwives, according to state data.

The law requires midwives to carry medical liability insurance and have a written collaboration with a physician.

That has created new challenges for licensed midwives like Mary Helen Ayres, in Bloomington, Ind. She said few insurance companies cover home birth midwives, and it's difficult to find a physician who will sign off on the collaboration.

"Doctors are very, very conscious of their liability and do not want to expand it, so I don't blame them," she said. "In exchange for legality, we have been burdened with a requirement for liability insurance; we have been burdened by the requirement for collaboration."

Ayers said these additional restrictions have only made it more difficult for midwives to practice in her state.

This story comes from a partnership between Iowa Public Radio and Side Effects Public Media — a public health news collaborative based at WFYI. Follow Natalie on Twitter @natalie_krebs.

Copyright 2022 Side Effects Public Media. To see more, visit Side Effects Public Media.