Loading...

Section Branding

Header Content

Drugmakers are slow to prove medicines that got a fast track to market really work

Primary Content

Doctors told Kristi Alcayaga it was time to bring out the "big gun" to fight her teenage son's leukemia. She expected the chemotherapy he was prescribed to be blue. Or red. Or some sinister color to convey its toxicity.

Instead, the drug called Clolar looked just like water.

By the time the IV bag filled with it was empty, Michael was sicker than he'd ever been in his more than six months of cancer treatment.

"He walked in the hospital and, you know, he never walked out," she said.

Michael died on May 20, 2014, a few weeks after his 16th birthday. Clolar turned out to be no match for the cancer. His mother said she thinks the drug's toxic side effects also may have hastened his death.

Ten years earlier, the Food and Drug and Administration had given the drug an expedited approval to treat pediatric lymphoblastic leukemia that had relapsed or failed to respond to two other treatments.

When there's an urgent need, the agency can grant what's known as an accelerated approval for a drug, like Clolar, based on preliminary evidence.

In the FDA's approval of Clolar, the agency noted there were no gold-standard clinical studies to show whether the drug prolonged patients' lives or improved their health.

In exchange for the accelerated approval, the drugmaker, Genzyme, agreed to do definitive follow-up studies to prove that Clolar really worked. But while that work was pending, the company was free to keep selling the drug.

But for nearly 18 years on the market, Clolar's most important confirmatory clinical trial remained incomplete. "Sanofi has been working closely with the FDA to fulfill this post marketing requirement and is still following this activity," Sanofi, which acquired Genzyme and Clolar more than a decade ago, wrote in a statement to NPR in May.

This week, the drug was finally converted to a regular approval, after the FDA declared its study commitment fulfilled.

That fact that Clolar hadn't been shown to extend patients' lives when her son was in treatment came as a surprise to Alcayaga, who lives in Everett, Wash., during a conversation with NPR. She said it's possible she just doesn't remember being told about it. Even if she knew there were missing pieces in the evidence backing clofarabine, the generic name for the toxic chemo, she said she would have still wanted it for Michael. He was out of options.

"If we hadn't done [the clofarabine], we might have been able to get some more time out of him," she said. "But ... I think then I would be kicking myself for not doing the clofarabine and giving it a try. It's just kind of this big, ugly circle that no one wants to be in because [you're] damned if you do, damned if you don't."

The tension Michael's family felt is at the heart of clinicians' and patients' decision-making around accelerated approvals.

A broken bargain for faster FDA action

The confirmatory trials FDA requires are meant to show either that the drugs were rightly fast-tracked and should stay on the market or that the original decisions were wrong and the drugs should be withdrawn.

But many studies aren't getting done. And in some cases they aren't starting at all. That means many drugs that made it to market with an accelerated approval are being used – sometimes for years – without patients, doctors or regulators knowing if they really work.

NPR analyzed 30 years of FDA and National Institutes of Health data and found that 42% of currently outstanding confirmatory studies, or 50 of them, either took more than a year to begin following accelerated approval or hadn't started at all. Nineteen of those required studies still haven't started three years or more after accelerated approval. Four of them haven't started more than ten years later.

Yet according to the federal accelerated approval regulation, confirmatory studies should "usually be studies already underway" when FDA approves a drug that way.

"It's crazy," says Gregg Gonsalves, a Yale professor and an advocate who pushed for faster FDA approval of drugs against AIDS in the 1980s. "It means that regulatory enforcement is lax and that the bargain that was made with accelerated approval – which was early access to markets [for drugmakers] and early access to drugs to patients, which is always contingent on verifying the clinical benefit of drugs – is broken in a way that needs serious repair."

NPR found that the FDA can also be lenient about deadlines for these confirmatory studies. For example, NPR identified 33 studies with anticipated completion dates that are a year or more behind their FDA due dates, accounting for about a quarter of all studies required of accelerated approval drugs that haven't yet been converted to regular approvals. However, this leaves out another 28% that are nowhere to be found in the clinical trials registry, indicating that they haven't begun.

Criticism of the accelerated approval process has mounted as the number of drugs being sold without completed clinical studies has grown. The issue threatened the Senate confirmation of Dr. Robert Califf as FDA commissioner earlier this year.

"Some companies have taken advantage of the Accelerated Approval Pathway, falling behind on providing confirmatory evidence, while FDA has shied away from using its authority to hold drug companies accountable for fulfilling their obligations," Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., wrote to Califf.

Wyden asked how the agency would hold companies accountable for failing to complete required confirmatory trials under accelerated approval. Acknowledging the problem, Califf wrote back, "it is incumbent upon the FDA to ensure that the work does not end with the initial approval."

Indeed, Dr. Rachel Sherman, who spent three decades at the FDA and served as principal deputy commissioner of food and drugs from 2017 until 2019, says the longer a drug is on the market without confirmatory trials, the less likely it is that its true clinical benefit will ever be studied and confirmed. "Then, you're left with a problem, because what do you do?"

Patients are already taking it, and some may even think it works. Though without a confirmatory trial, it's not clear. Nevertheless, she added, "the company is very happy selling it."

Prices rise while drug data stalls

While companies making drugs with accelerated approvals drag their feet to start confirmatory studies, they are also more likely to increase the prices of those drugs, according to GoodRx, a website that helps patients get discounts on drugs.

GoodRx conducted a pricing analysis at NPR's request and found that, on average, drugs granted accelerated approval have 26% more price increases over 10 years than other medicines.

Gonsalves likened this to "tapping the brakes" on confirmatory studies while "pressing the accelerator" on price. "It doesn't surprise me that they're trying to ratchet up the ability to reap profits. At the same time, they're sort of sluggish in their statutory duty to provide timely initiation and completion of studies."

How it began

The accelerated approval process got its start during the height of the AIDS epidemic.

In the late 1980s, JT Anderson, now 78, remembers how he and his partner decided not to get tested for HIV. They knew that if they did, there was only one drug available, azidothymidine, commonly referred to as AZT.

The FDA reviewed and approved AZT in 107 days, which then-FDA Commissioner Frank Young said was an agency record. While the drug was effective in prolonging the lives of some patients with AIDS, it had major side effects, including severe anemia, and by itself could not hold HIV in check for very long.

"It would be very scary if we tested positive," Anderson says. "At that time, it was a death sentence. I don't think either one of us wanted to face that."

It can take 10 years or more to bring a new drug to market, but AIDS cases and deaths were climbing. Anderson remembers when someone he knew in the activism community died every month, prompting a funeral march each time down Los Angeles' Santa Monica Boulevard.

In 1988, he traveled with members of the LA chapter of advocacy group ACT UP to FDA headquarters outside Washington, D.C., for one of the group's biggest protests yet. The activists demanded that the agency allow more HIV drugs onto the market – and faster.

Even as people were arrested around him, Anderson was inspired.

"There were employees at the window, and many of them were cheering and many of them were waving," Anderson says. "So there was some encouragement that they were trying to say, 'We're with you.' "

In 1991, the drug didanosine, nicknamed DDI, became the second HIV treatment after AZT to win FDA approval, and the first to do so using a new approach.

Instead of waiting to find out whether patients taking the drug lived longer, researchers gauged the effect of the medicine on a particular kind of white blood cell that is critical for the body's immune response. HIV depletes these CD4 cells, so a medicine that improved patients' CD4 count was presumed to be beneficial.

"Now, it sounds very easy, but there was a huge risk," said Sherman, who was at the FDA at the time.

The FDA allowed the approval if the drugmaker committed to finishing two clinical trials already underway and agreed to withdraw the drug from the market if those trials didn't confirm efficacy.

"Within less than a year, it, in fact, confirmed clinical benefit and we were able to convert it to a traditional approval," Sherman said. "So that was the first accelerated approval, even though it wasn't called that."

In 1992, the FDA formalized accelerated approval in a regulation based on the didanosine example. For HIV drugs that then went down this path, the studies were already underway at the time of accelerated approval. The results allowed the FDA to confirm they worked and convert them to regular approvals fairly quickly, Sherman said.

But that precedent didn't last.

Dr. Jacqueline Corrigan-Curay, principal deputy center director in FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, told NPR in an interview that the agency would like to always have these confirmatory studies underway at the time of accelerated approval. But there's no regulatory requirement.

"If you have the data and it meets accelerated approval and there's this unmet medical need, we need to go forward" with the approval, she said.

She said that most accelerated approvals do eventually go on to be converted to regular approvals or withdrawn, and that only around 10% are still waiting for evidence after five years.

Penalizing companies that don't meet accelerated approval requirements is on the agency's list of planned guidance documents for 2022, however. And the agency's 2023 budget document includes legislative proposals that would give the FDA more power to solve the problem of tardy trials.

Unclear tradeoffs for patients and clinicians

One problem for patients and doctors is that it can be difficult to know if a drug has an accelerated approval — and open questions about its ultimate safety and effectiveness.

The FDA team reviewing antiretroviral drugs to treat HIV, which accounted for about a half of all accelerated approvals in the 1990s, decided to add special warnings to the drug labels in bold, black boxes.

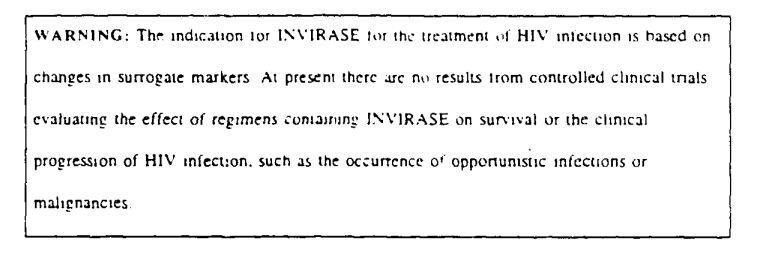

For example, Roche's HIV drug Invirase, known generically as saquinavir, got a boxed warning in the FDA-approved instructions for its use in 1995.

The warning stated that Invirase was approved based on so-called surrogate endpoints – in this case, raising counts of a particular type of white blood cell. But there were no results from clinical trials measuring whether the drug helped patients live longer.

Sherman, who was working in the FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research at the time, says that was her responsibility.

"We were approving them so fast that there was no literature for doctors to look at," she said, explaining that doctors didn't know what an accelerated approval was, so her team wanted to make sure the use of a surrogate endpoint instead of a clinical one was clear.

But there's no regulation requiring this kind of prominent disclosure and no agency-wide policy mandating it either.

"Now, you won't see that anymore," she said.

Parking lot labor

Brittany Bonds found out the hard way about the limitations of accelerated drug approval. She went into premature labor in a Walmart parking lot near Imperial, Mo., with two kids in the back seat of her car. She was 30 weeks pregnant.

"Oh, my God, I don't know if I can drive home," she recalled thinking that day in November 2019.

As in her two previous pregnancies, she'd taken a drug called Makena to prevent her baby from arriving dangerously early. And for the third time, it hadn't worked.

The FDA gave Makena an accelerated approval in 2011, under the condition that the drugmaker conduct additional studies to confirm it is effective.

Bonds says it wasn't clear to her that Makena had been approved on weaker evidence than other drugs and the FDA was awaiting more clinical trial results. She's suing the manufacturer as part of a class action lawsuit.

"It's just crazy that they can have this product out there and have all that information, and it's just not really hashed out there for the public, " said Bonds. " Because if you just go on [Makena's] website, there's just big quotes and words about it working and how great it is and the benefits about it."

Unlike the HIV drugs that received accelerated approval in the 1990s, there is no boxed warning about the data gaps on Makena's label. Instead there's a small note under Makena's indication that reads, "There are no controlled trials demonstrating a direct clinical benefit, such as improvement in neonatal mortality and morbidity."

The drug's website, complete with a tiny baby in a knitted pink hat, includes the slogan, "Help give your baby more time to develop with Makena." The words "accelerated approval" are nowhere to be found.

Corrigan-Curay, of the FDA, said it's up to prescribers to communicate with patients about the limitations of accelerated approvals. For its part the agency strives to be transparent, she said, publishing its lists of accelerated approvals, which NPR used in its analysis, as well as other explanatory web pages for patients.

The Bonds' baby was born on a stretcher on the side of the road between their car and the ambulance. He weighed 3 pounds, 9 ounces. Named Phoenix, the preemie would spend the next 83 days in the neonatal intensive care unit and still has health issues.

Makena's main confirmatory trial was finished in 2018, two years behind the schedule set by the FDA. The study showed the drug didn't reduce preterm births after all, according to the agency.

Upon reviewing the confirmatory study and other data (including some that backed keeping the drug available), the FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research recommended in October 2020 that Makena be pulled from the market. But because the drugmaker didn't voluntarily withdraw the drug, a hearing to discuss its potential withdrawal is required and isn't expected to happen until this fall at the earliest. Meanwhile, Makena remains on the market.

In November 2020, Covis Pharma acquired the company that previously made Makena. Francesco Tallarico, head of goverment affaris and policy at Covis Pharma, says it has proposed conducting further research to "fully explore the potential of Makena as a treatment option for a high-risk patient population."

"Given the absence of other approved treatments for recurrent preterm birth and the studied safety of the product, we believe it would be a serious mistake to take this option off the table for physicians, particularly without further research into which patients might benefit most from access to Makena," Tallarico says.

Makena is one of 13 drugs that got accelerated approvals and whose confirmatory studies were finished more than a year ago yet still haven't been either converted to a regular approval or taken off the market by FDA, an NPR analysis found. Some of these drugs have had completed studies for six, seven or even 22 years. Yet they're still in limbo.

Accelerated approvals grow more common

For the first two decades that accelerated approval was an option, the FDA granted only a few each year. After a 2012 law formalized the agency's policy, the approvals boomed.

In 1992, there was just one accelerated approval. But in 2020, there were 49, according to NPR's analysis. Twenty-eight of those 2020 accelerated approvals were for new drugs, and the rest were for expanded uses of existing medicines.

Today, there are around 200 drugs with accelerated approvals. But now, many of them have more than one accelerated approval use, especially if the drug treats cancer.

For example, Keytruda, a Merck drug, has more than 30 accelerated approvals. They range from treatment of melanoma to cervical cancer to lung cancer. Sixteen are for changes in Keytruda doses for previously approved uses. Merck contends the 16 dose changes should be counted once, but the FDA assigned each its own regulatory number.

AIDS crisis opened Pandora's box

To Gregg Gonsalves, the Yale professor, the drug industry had been waiting for a way to "crack open" the FDA in terms of deregulation for years. Accelerated approvals turned out to be that tool, he said.

"AIDS activists did it for them, right?," he said, adding that he was part of the protest at the FDA in 1988. "You know, we were saying, 'The FDA is killing us.'... But by the early 90s, you're like, 'Oh my God, you know, we opened a Pandora's box.' "

The Government Accountability Office's first investigation of accelerated approvals in 2009 – nearly two decades after accelerated approvals began – found problems with the FDA's monitoring of postmarket confirmatory studies. In particular, the GAO faulted the agency for its inaction when the studies weren't completed on time or failed to prove the drugs were effective.

"The promise of accelerated approval is that you're going to get access and answers," said Gonsalves. "And what happens is you got the drugs on the market, but you didn't find out if they worked."

The GAO recommended that the FDA spell out when it would expedite withdrawing drugs from the market that received accelerated approvals. But ultimately, the FDA disagreed and didn't implement the GAO's recommendation.

But in 2010, the FDA said for the first time it would withdraw a drug's accelerated approval over a failure to complete confirmatory studies.

The drug called Proamatine raises blood pressure and received an accelerated approval in 1996. Patients who need it have orthostatic hypotension – their blood pressure drops when they stand up from sitting or laying down, causing them to feel dizzy or faint.

Drugmaker Shire had four years to complete Proamatine's confirmatory studies, according to the FDA approval letter. While the agency waited for the results, the drug generated millions of dollars in sales.

According to Shire's financial filings, Proamatine generated $23.7 million in sales for 2000 and $38 million in 2001.The GAO estimated that Proamatine had generated nearly $238 million in sales from 1996 through 2008.

Even in 2008, a dozen years after the drug's accelerated approval, the company hadn't fulfilled its study obligations.

NPR found one confirmatory study that matched the FDA's description in its letter of approval for the drug and wrapped up in late 1999. But the FDA deemed the drugmaker's postmarketing trials "inconclusive," according to a 2010 Shire statement. FDA records show that the drugmaker was given a new deadline: March 31, 2015.

But Shire discontinued the drug in 2010 and never did another confirmatory study. Several generics had already entered the market starting in 2003.

In 2010, the FDA said it would move to withdraw the Proamatine generics, too, but a few weeks later, it reversed its decision when patients objected. Now, more than 25 years later, the drug's clinical efficacy remains unconfirmed, and the accelerated approval has not been converted to a regular approval.

Takeda, which acquired Shire in 2019, did not answer NPR's questions about the incomplete confirmatory study, explaining that it acquired Shire after Proamatine was discontinued.

The FDA has withdrawn at least 28 accelerated approvals in all. But that process is slow and takes, on average, more than seven years, according to NPR's analysis.

Risky drug or death

So far, almost half of all accelerated approvals have been converted to regular approvals following confirmatory studies that showed the drugs worked; only 9% have been withdrawn, NPR's analysis of FDA data found.

For many patients, particularly those with cancer, accelerated approvals have made new treatments available faster.

The alternative can be death, said Phil McCartin, a patient advocate. He and his wife, Lorraine, who's been cancer-free for a decade, have spent years advocating for early access to drugs.

The McCartins met after both of their first spouses died of cancer in the early 1990s. Then, in 2006, Lorraine found out she had breast cancer, and that it had already spread to her lymph nodes. Soon, it was in her liver.

The cancer was aggressive. Lorraine would improve on one treatment, but it stopped working within a few months. Her doctors would then try another. By 2010 she was running out of options. The disease was spreading and her symptoms were getting "out of control," she said.

That's when her doctors told her about an experimental drug called Kadcyla that was being developed by Genentech. They said the drug was expected to get accelerated approval by September of that year.

But when Phil picked up his morning newspaper one Saturday that summer, he saw some bad news: The FDA had denied Kadcyla accelerated approval.

Finally someone suggested they try getting the drug through expanded access, which allows patients to receive unapproved drugs outside of clinical trials. There were no expanded access programs in New England, where the McCartins lived, but there was one in Virginia.

The couple made 16 trips at their own expense to be part of it, something they know not every patient can do.

"Her cancer melted away in less than a year," Phil said. "She had seven miserable tumors in her liver. She had a tumor squeezing her bile duct shut. She had a tumor squeezing her right kidney. She had tumors squeezing her adrenal glands on top of her liver shut, and it all melted away in less than a year. And it never has come back."

Today, the McCartins advocate for more accelerated approvals, not fewer.

Sherman, the former FDA leader, said the agency has to balance risks. "There's the risk of putting the drug on the market and it doesn't work," Sherman said. "Also, there's a risk of not putting on the market a drug that will work. And that's a terrible risk, too, because that also can harm people and kill people."

Faster approval and false hope

The FDA made what many consider its most controversial accelerated approval yet on June 7, 2021, when it allowed Biogen's Aduhelm on the market to treat Alzheimer's disease even though its advisory committee of outside experts voted against the approval and some within the FDA opposed the move.

"Accelerated approval is not supposed to be a backup," said Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, a professor who runs the Program on Regulation, Therapeutics and Law at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital. "In this case, they [the FDA] learned about the drug. They found out that there is no good evidence that the drug works. And then they went back and said, 'Well, let's do accelerated approval anyway.' And I don't think that's right."

FDA's surprising approval of Aduhelm prompted three expert members of an agency advisory committee to resign, including Kesselheim.

Biogen has until 2030 to complete Aduhelm's confirmatory trial.

"In many cases, even if they're given a number of years to complete their confirmatory studies, some of these confirmatory studies are delayed and are not completed in a timely fashion," said Kesselheim, who has done his own research into accelerated approvals over the years. "And so it leads you to wonder, after nine years, could we still be waiting for information on this drug?"

Biogen spokesperson Allison Parks told NPR the company expects to wrap up its confirmatory study in half the time FDA anticipated. NIH records indicate the study began on June 2 and is still recruiting patients.

Leukemia drug remains in limbo

Back to Clolar, the leukemia drug that FDA gave an accelerated approval to in 2004 and that was unsuccessful in treating teen Michael Alcayaga a decade later.

The medicine epitomizes the idea that for patients in need, a faster, though riskier, regulatory path offers hope. Less proof is needed upfront so that a drug can be made available more quickly. But the express lane comes with a promise to get a definitive answer sooner than later.

Clolar "was approved based on a pair of clinical trials involving only a total of 66 pediatric patients who had [acute lymphoblastic leukemia] that had returned," said Dr. Mikkael Sekeres, chief of hematology at the Sylvester Cancer Center at University of Miami and author of the upcoming book Drugs and the FDA: Safety, Efficacy and the Public's Trust.

Less than a third of the children responded to Clolar, but it was approved as a last resort for pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who had relapsed or didn't respond after two prior therapies. As a condition of approval, FDA required Genzyme to study the drug further.

Genzme's plan for the confirmatory phase 3 study was due to the FDA just two months after its approval at the end of 2004.

"We don't forget about these, but I can't comment about what the agency may be doing about a particular product," Corrigan-Curay of the FDA told NPR in May.

The agency converted the accelerated approval to a regular approval on July 18, though it's unclear which study in the federal clinical trials registry satisfied FDA's original requirements. There appears to be no Sanofi-funded phase 3 trial of the drug in pediatric patients with ALL listed in the registry. By the time of publication, Sanofi had not yet answered NPR's question about the study used.

Until recently, the FDA's record about the Clolar study requirement called it delayed, but said the drugmaker "plan[ned] to submit alternate study data." Its most recent new deadline was listed as Dec. 31, 2019. According to the FDA letter to the company declaring its study commitment fulfilled, the company submitted its final report in October 2021.

Still, Sekeres said the Clolar lag is a "travesty."

Asked who was to blame for the 18-year delay, Sekeres said both Sanofi and the FDA.

"[The drugmaker is] committing to doing this and they're failing our patients by not completing these trials to at the very least confirm the initial benefit seen in a limited population of patients to gain accelerated approval," he said. "On the other hand, it is also on the FDA to police this and to even invoke withdrawal of medications and I think it's hard for a couple of reasons."

A withdrawal triggered by the absence of a confirmatory study could be devastating if the drug in fact really does improve overall survival. And regardless, withdrawals could erode public trust in the FDA, Sekeres said.

"Patients are taking these drugs and they feel they're getting a benefit from them, and it makes it difficult," Corrigan-Curay said. "As a regulatory agent, we have to make difficult decisions, but it is complex. And we haven't forgotten about that. We don't say, 'Well, you know, that's it.' We still think about it and think about what we can do even in these most difficult cases."

For six cancer drug indications last year, that meant holding an advisory committee hearing to address "dangling" accelerated approvals. Since the meeting, three indications have been withdrawn, another got a narrower indication and two more are still awaiting more data.

NPR researcher Brin Winterbottom helped fact-check this story.

You can contact NPR pharmaceuticals correspondent Sydney Lupkin at slupkin@npr.org.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.