Section Branding

Header Content

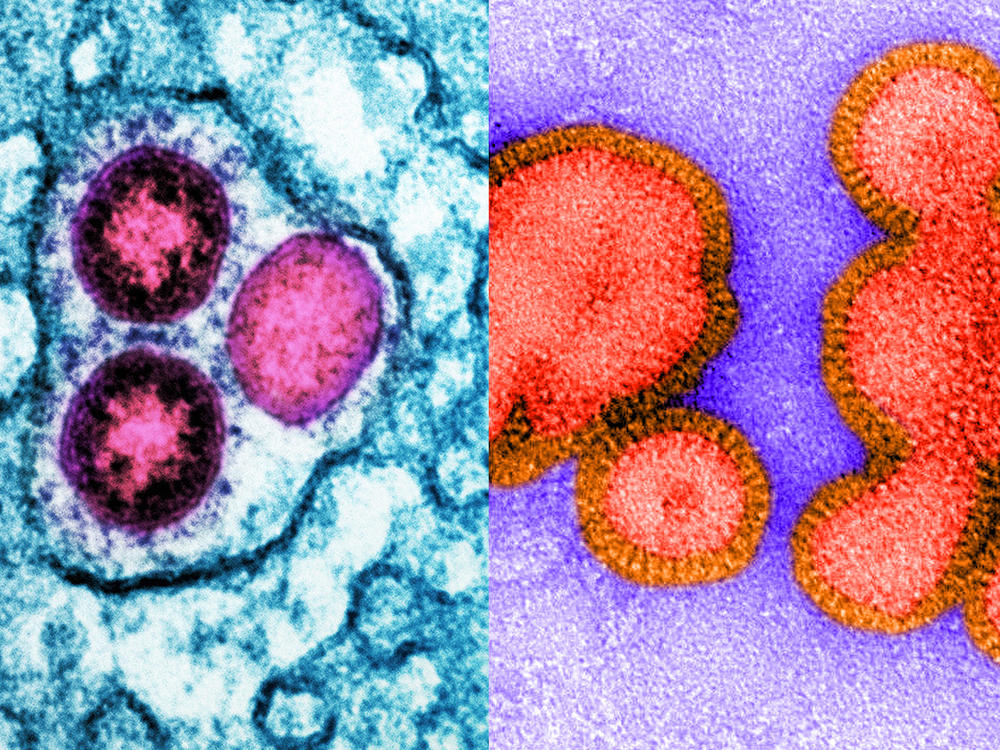

Flu is expected to flare up in U.S. this winter, raising fears of a 'twindemic'

Primary Content

The flu virtually disappeared for two years as the pandemic raged. But influenza appears poised to stage a comeback this year in the U.S., threatening to cause a long-feared "twindemic."

While the flu and the coronavirus are both notoriously unpredictable, there's a good chance COVID cases will surge again this winter, and troubling signs that the flu could return too.

"This could very well be the year in which we see a twindemic," says Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease professor at Vanderbilt University. "That is, we have a surge in COVID and simultaneously an increase in influenza. We could have them both affecting our population at the same time."

The strongest indication that the flu could hit the U.S. this winter is what happened during the Southern Hemisphere's winter. Flu returned to some countries, such as Australia, where the respiratory infection started ramping up months earlier than normal, and caused one of the worst flu seasons in recent years.

What happens in the Southern Hemisphere's winter often foreshadows what's going to happen north of the equator.

"If we have a serious influenza season, and if the omicron variants continue to cause principally mild disease, this coming winter could be a much worse flu season than COVID," Schaffner warns.

And the combination of the two viruses could seriously strain the health system, he says. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that flu causes between 140,00 and 710,000 hospitalizations annually.

"We should be worried," says Dr. Richard Webby, an infectious disease specialist at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital. "I don't necessarily think it's run-for-the-hills worried. But we need to be worried."

The main reason the flu basically disappeared the last two years was the behavior changes people made to avoid COVID, such as staying home, avoiding public gatherings, wearing masks, and not traveling. That prevented flu viruses from spreading too. But those measures have mostly been abandoned.

"As the community mitigation measures start to roll off around the world and people return to their normal activities, flu has started to circulate around the world," says Dr. Alicia Fry, who leads influenza epidemiology and prevention for the CDC. "We can expect a flu season this year — for sure."

Young kids at especially high risk

The CDC is reporting that the flu is already starting to spread in parts of the south, such as Texas. And experts caution very young kids may be especially at risk this year.

Though COVID-19 generally has been mild for young people, the flu typically poses the biggest threat to both the elderly and children. The main strain of flu that's currently circulating, H3N2, tends to hit the elderly hard. But health experts are also worried about young children who have not been exposed to flu for two years.

"You have the 1-year-olds, the 2-year-olds, and the 3-year-olds who will all be seeing it for the first time, and none of them have any preexisting immunity to influenza," says Dr. Helen Chu, assistant professor of medicine and allergy and infectious diseases and an adjunct assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of Washington.

In fact, the flu does appear to have hit younger people especially hard in Australia.

"We know that schools are really the places where influenza spreads. They're really considered the drivers of transmission," Chu says. "They'll be the spreaders. They will then take it home to the parents. The parents will then take it to the workplace. They'll take it to the grandparents who are in assisted living, nursing home. And then those populations will then get quite sick with the flu."

"I think we're heading into a bad flu season," Chu says.

'Viral interference' could offset the risks

Some experts doubt COVID and flu will hit the country simultaneously because of a phenomenon known as "viral interference," which occurs when infection with one virus reduces the risk of catching another. That's an additional possible reason why flu disappeared the last two years.

"These two viruses may still both occur during the same season, but my gut feeling is they're going to happen sequentially rather than both at the same time," Webby says. "So I'm less concerned about the twindemic."

Nevertheless, Webby and others are urging people to make sure everyone in the family gets a flu shot as soon as possible, especially if the flu season arrives early in the U.S. too. (Most years officials don't start pushing people to get their flu shots until October.)

So far it looks like this year's flu vaccines are a good match with the circulating strains and so should provide effective protection.

But health officials fear fewer people will get flu shots this year than usual because of anti-vaccine sentiment that increased in reaction to COVID vaccinations. Flu vaccine rates are already lagging.

"We are worried that people will not get vaccinated. And influenza vaccine is the best prevention tool that we have," the CDC's Fry says.

Fry also hopes that some of the habits people developed to fight COVID will continue and help blunt the impact of the flu.

"The wild card here is we don't know how many mitigation practices people will use," Fry says. "For example, people now stay home when they're sick instead of going to work. They keep their kids out of school. Schools are strict about not letting kids come to school if their sick. All of these types of things could reduce transmission."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.