Section Branding

Header Content

In broiling cities like New Orleans, the health system faces off against heat stroke

Primary Content

As the hour creeps past three in the afternoon, New Orleans' streets are devoid of tourists and locals alike. The heat index is over 105 degrees.

At the city's ambulance depot, the concrete parking lot seems to magnify the sweltering heat, circulating the air like a convection oven.

New Orleans Emergency Medical Services has been busy this summer, responding to heat-related emergency calls and rushing patients to nearby hospitals.

Capt. Janick Lewis and Lt. Titus Carriere demonstrate how they can load a stretcher into an ambulance using an automated loading system.

Lewis wipes sweat from his brow as the loading arm whirs and hums, raising the stretcher into the ambulance — "unit" in official terminology.

But the mechanical assistance isn't the best thing about the new vehicle. "The nicest thing about being assigned a brand new unit, is it's a brand-new air conditioning system," Lewis says.

The new AC is much more than just a luxury for the hard-working crews. These days they need the extra cooling power to help save lives.

"The number one thing you do take care of somebody is get them out of the heat, get them somewhere cool," Lewis says. "So the number one thing we spend our time worrying about in the summertime is keeping the truck cool."

Like much of the country, New Orleans has been embroiled in an almost relentless heat wave for weeks. As a result, more people are falling ill with heat-related conditions than ever before. Just last week, EMS responded to 29 heat-related calls — more than triple compared to the same period last year.

As the city's emergency medical systems deal with the influx of patients, scientists say these dangerous heat levels — and the increasing stress they put on human bodies and medical systems — may be the new norm.

At the same time, New Orleans EMS has struggled with funding and staffing challenges. It's currently operating with only 60% of its needed staff. The city's chief of EMS has called for increased funding for higher wages to attract more workers.

Lewis says they're making do with the resources they have, and prioritizing one-time expenses like new ambulances to help them meet the challenges they're facing.

"We're going to provide the care everybody needs, regardless of how hot it gets," Lewis says. "We'd love to have all the help in the world, but we're getting the job done with what we have right now."

Health dangers above 100℉

When a human being is exposed to high levels of heat for too long, it starts to raise the core body temperature. Once that exceeds 100 degrees, hyperthermia can develop. That can prompt an escalating cascade of health problems if it isn't quickly addressed.

The first stage is heat exhaustion, Lt. Carriere explains: "That means you're hot, you may have an elevated temp, but you also have what's called diaphoresis, which means your body is sweating, is still trying to compensate and cool yourself off." You'll also likely have other symptoms like weakness, dizziness, and headache.

Carriere says that if you can quickly get out of the heat and into some AC, generally you'll recover from heat exhaustion on your own. But if you don't, your core temperature will continue to rise.

Near 104° the dangers escalate

If internal body temperature approaches 104 degrees, you could succumb to the next stage — heat stroke.

"Once you move to heat stroke, your body stops compensating," Carriere says. "You stop sweating. You're hot. You're dry, and your organs are basically like frying themselves from the inside out."

When you stop sweating, it becomes even harder for your body to cool itself down. During heat stroke, you may also experience other severe symptoms like an altered state of mind, confusion, and a rapid, erratic pulse. You may even lose consciousness.

Heat illness can develop after unrelieved exposure to incessant heat, but high humidity compounds the problem by making it harder for the body to cool itself by sweating.

Working outdoors, dehydration, alcohol or drug use, and sunburn all increase the risk. The very old, children under 4, and those who are obese or have certain medical conditions are particularly vulnerable.

Without medical intervention, heat stroke can be deadly. EMS starts treatment immediately after they arrive on the scene.

"We'll get them on a gurney, get them into the unit, start removing their clothing and put ice packs wherever applicable to try to cool them down," says Carriere.

Saving lives in the ER with ice, fluids, and medical support

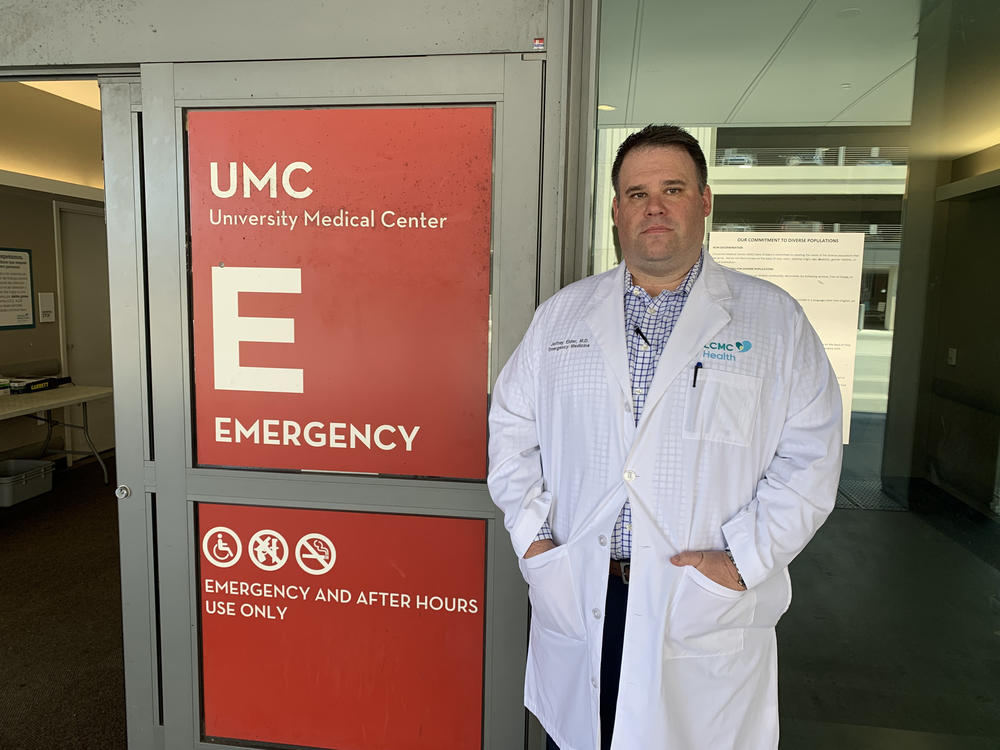

Once you're loaded into the ambulance, they'll race you to a nearby hospital, Carriere says. At University Medical Center (UMC), the city's largest hospital, doctors and nurses will continue efforts to quickly lower body temperature, and replace fluids by IV if necessary..

"When the patient ends up at the hospital, we're going to continue that cooling process," Elder says. "We're going to put them in an ice water bath," says Dr. Jeffrey Elder, the Medical Director for Emergency Management at UMC. "We may use some misting fans and some cold fluids to get their body temperature down to a reasonable temperature while we're supporting all the other bodily functions."

Getting your core temperature down as quickly as possible is the highest priority, Elder explains, and is what will ultimately save your life. One way they can speed that along is by burying you in ice. In other parts of the country, doctors actually place patients inside body bags pre-packed with pounds of ice. Body bags are useful in these cases because they're waterproof and are designed to closely fit the human form.

They don't use body bags at UMC's emergency room, but during the summer, staffers do keep bags of ice ready to go at all times.

"On the stretcher, we'll use some of the sheets as kind of a barrier," Elder says. "And while they're on the stretcher, we'll just put the ice on them right then and there."

Hospital staff will continue to work to cool you down until your temperature gets back below 100. That's when you're considered to be in the medical safe zone.

Elder admits that while it always gets hot in New Orleans during the summer, his emergency room has been treating more heat-related illness in 2023 than ever before. A few patients have died from the heat.

Like many other hospital systems, UMC is struggling with staffing challenges since the pandemic. But UMC has prioritized staffing of the emergency department in order to handle things like an influx of patients from heat-related illness, Elder says.

Burden on health infrastructure heats up

Across the country, meteorological events like heat waves and heat domes will become more frequent and intense in the future, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"Extreme summer heat is increasing in the United States," says Claudia Brown, a health scientist with the CDC's Climate and Health Program. "And climate projections are indicating that extreme heat events will be more frequent and intense in the coming decades."

Health infrastructure will be challenged to keep up in order to treat patients suffering from extreme heat exposure. In New Orleans, both first responders and doctors say they expect to see more patients with heat-related illness. July is merely the halfway point of a Louisiana summer.

"We haven't even gotten to the hottest part yet, which is typically August to September," says EMS Lt. Titus Carriere. "So I'm expecting it to get pretty bad."

This story comes from NPR's health reporting partnership with the Gulf States Newsroom and KFF Health News.

Copyright 2023 Gulf States Newsroom. To see more, visit Gulf States Newsroom.