Section Branding

Header Content

Japanese scientists race to create human eggs and sperm in the lab

Primary Content

Katsuhiko Hayashi pulls a clear plastic dish from an incubator and slides it under a microscope.

"You really want to see the actual cells, right?" Hayashi asks as he motions toward the microscope.

Hayashi, a developmental geneticist at Osaka University in Japan, is a pioneer in one of the most exciting — and controversial — fields of biomedical research: in vitro gametogenesis, or IVG.

The goal of IVG is to make unlimited supplies of what Hayashi calls "artificial" eggs and sperm from any cell in the human body. That could let anyone — older, infertile, single, gay, trans — have their own genetically related babies. Besides the technical challenges that remain to be overcome, there are deep ethical concerns about how IVG might eventually be used.

To provide a sense of how close IVG may be to becoming a reality, Hayashi and one of his colleagues in Japan recently agreed to let NPR visit their labs to talk about their research.

"Applying this kind of technology to the human is really important," Hayashi says. "I really, really get excited about that."

From mice to humans

Through the microscope, the cells in Hayashi's dish look like shimmering silver blobs. They're a type of stem cell known as induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPS.

"[The] iPS cells actually form a kind of island — they grow while touching each other," Hayashi says. "So they look like an island."

IPS cells can be made from any cell in the body and then theoretically can morph into any other kind of cell. This versatility could one day help scientists solve a long list of medical problems.

Hayashi was the first to figure out how to use iPS cells to make one of the first big breakthroughs in IVG: He turned skin cells from the tails of mice into iPS cells that he then turned into mouse eggs.

Hayashi takes another rectangular dish from the incubator to explain how he did it. The dish contains ovarian organoids — structures he created that can nurture cells made from iPS cells into becoming fully mature eggs.

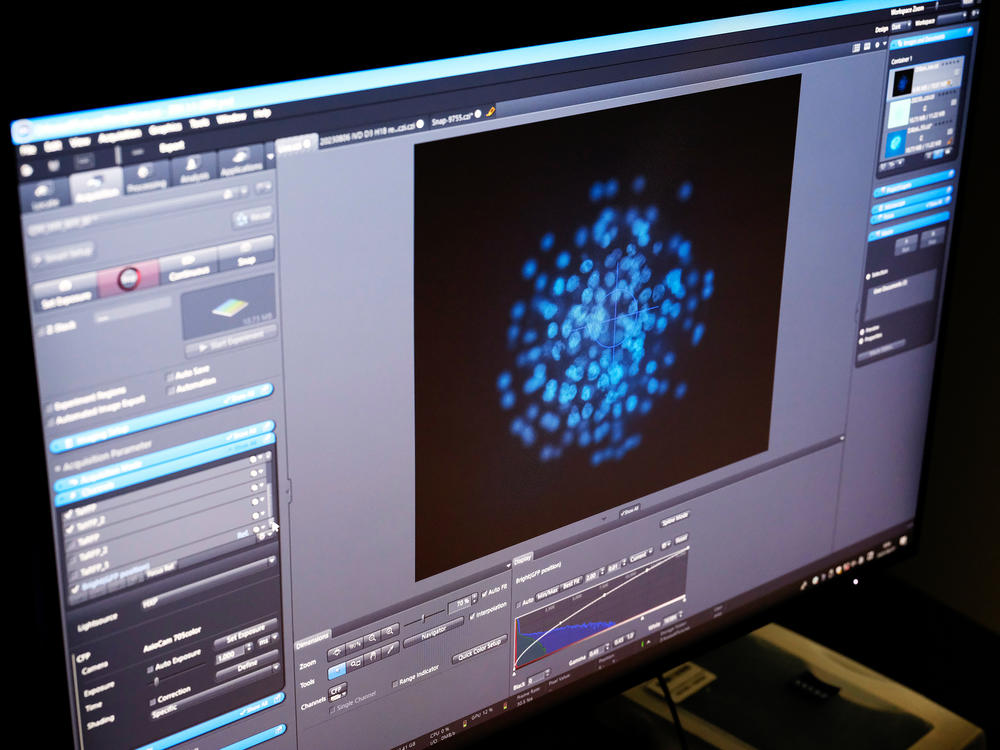

Under the microscope, each egg looks like a glowing blue ball. Dozens are clearly visible.

"Basically we can get 200 immature eggs in one ovarian organoid," Hayashi says. "In one experiment, basically we can make like 20 ovarian organoids. So in total like 4,000 immature eggs can be produced."

Hayashi used mouse eggs like these to do something even more groundbreaking — breed apparently healthy, fertile mice. That sent scientific shock waves around the world and triggered an international race to do the same thing for people.

Researchers at a biotech startup called Conception, based in California, claim they're about to lap the Japanese scientists. Within a year, they say they'll be ready to make human eggs they hope to try to fertilize to make human embryos. But the Americans have released few details to back up their claim.

Hayashi's skeptical.

"It's impossible," Hayashi says. "In my opinion — one year — I don't think so."

Unraveling the biology of human egg development just doesn't move that fast, he says.

That said, Hayashi thinks it's not a question if IVG will ever happen. It's more a question of when, he says, and that he and his colleagues in Japan are at least as close as the Americans to making "artificial" human embryos.

Hayashi predicts they'll have an IVG egg ready to try to fertilize within five to 10 years.

Coaxing primitive eggs to maturity

But to see how close they are, Hayashi recommends a visit with his colleague, Mitinori Saitou, who directs the Advanced Study of Human Biology Institute at Kyoto University.

Saitou's the first — and so far only — scientist to release a carefully validated scientific report documenting how he created the first human eggs through IVG. Those eggs were too immature to be fertilized to make embryos. But Saitou and Hayashi are working hard on that.

Saitou heads into his lab.

"That's the cell culture room," Saitou says. "Kind of [the] most important place."

It's the most important place because this is where Saitou is trying to figure out how to get his IVG human eggs to mature enough so they can be fertilized.

"For example, we are trying to understand signals that instruct a cell's maturation," Saitou says. He is also trying to identify key genes necessary for egg development.

Three scientists are huddled around microscopes in the cramped culture room jammed with equipment. They are examining their latest batch of very immature human eggs, and mixing them with other cells to see which chemical signals are necessary to coax them into full maturity.

"We use mouse cells and also human cells," Saitou says, though he won't get more specific because he hasn't published the protocol yet in a scientific journal.

Just then, one of the scientists jumps out of his chair, cradling one of the dishes as he heads to another room.

"They're bringing these cells to check cells' condition," Saitou explains.

Like Hayashi, Saitou is also skeptical of the claims by Conception, the U.S. biotech company.

"Some sort of incredible scientific breakthrough may happen. But let's see," Saitou says, laughing.

When asked how close he is to success, Saitou demurs.

"We are working on that. That's not yet published so I cannot tell," he says.

In addition to waiting to publish their research before making any claims, the Japanese scientists also warn that many years of experimentation would be needed to make sure artificial IVG embryos aren't carrying dangerous genetic mutations.

"They may cause some sort of diseases, or maybe cancer, or maybe early death. So there are many possibilities," Saitou says. "Even single mutations or mistakes are really disastrous."

IVG could make new kinds of families possible

Even if IVG can be shown to be safe, the Japanese scientists are also being cautious for another reason: They know IVG would raise serious moral, legal and societal issues.

"There are so many ethical problems," Saitou says. "This is the thing that we really have to think about."

IVG would render the biological clock irrelevant, by enabling women of any age to have genetically related children. That raises questions about whether there should be age limits for IVG baby-making.

IVG could also enable gay and trans couples to have babies genetically related to both partners, for the first time allowing families, regardless of gender identity, to have biologically related children.

Beyond that, IVG could potentially make traditional baby-making antiquated for everyone. An unlimited supply of genetically matched artificial human eggs, sperm and embryos for anyone, anytime could make scanning the genes of IVG embryos the norm.

Prospective parents would be able to minimize the chances their children would be born with detrimental genes. IVG could also lead to "designer babies," whose parents pick and choose the traits they desire.

"That [would] mean maybe exploitation of embryos, commercialization of reproduction. And also you could manipulate genetic information of those sperm and egg," says Misao Fujita, a bioethicist at the University of Kyoto who's been studying Japanese public opinion about IVG.

The Japanese public is uncomfortable with IVG for those reasons. But the Japanese would even be uneasy about using this technology to create babies outside of traditional family structures, she says.

"If you can create artificial embryos, then that mean[s] maybe a single person can create their own baby. So who is [the] mother and father? So that means social confusion," Fujita says.

Japan doesn't even have laws that would recognize a child created by a single parent or gay marriage. The use of IVG by anybody except a heterosexual married couple isn't popular in Japan either, Fujita says.

Despite the concerns, the Japanese government is considering allowing scientists to proceed with creating IVG embryos for research.

Fujita, who's on the committee the government formed to consider this, supports that.

"The technology of IVG, its purpose is not only [to] have a baby — genetically related baby — but there are many benefits and good things you can know from the basic research," she says, such as finding new ways to treat infertility and prevent miscarriages and birth defects.

Others aren't so sure.

"There [are] many concerns for me," says Azumi Tsuge, a medical anthropologist at the Meiji Gakuin University in Tokyo.

When she told friends about the scientific work, they were surprised, she says. They asked her why the government would permit it and why scientists would want to move ahead with it.

A particular worry for Tsuge is how the technology might be used to try to weed out what might be considered unwanted genetic variation, making Japan an even more homogenous society than it already is.

She says there needs to an open public debate before the government makes a decision on the creation of human IVG embryos. "Why is [it] necessary?" she asks. "They need to explain and we need ... discussion."

The scientists, too, are uncomfortable with some of the ways IVG could be used, such as outside traditional families. But they note that IVF was controversial at first, too. Society has to decide how best to use IVG, they say.

"Science always have good aspect and also ... negative impact," says Kyoto University's Saitou. "Like atomic bombs or any technological development, if you use it in a wise manner, it's always good. But everything can be used in a bad way."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.