Section Branding

Header Content

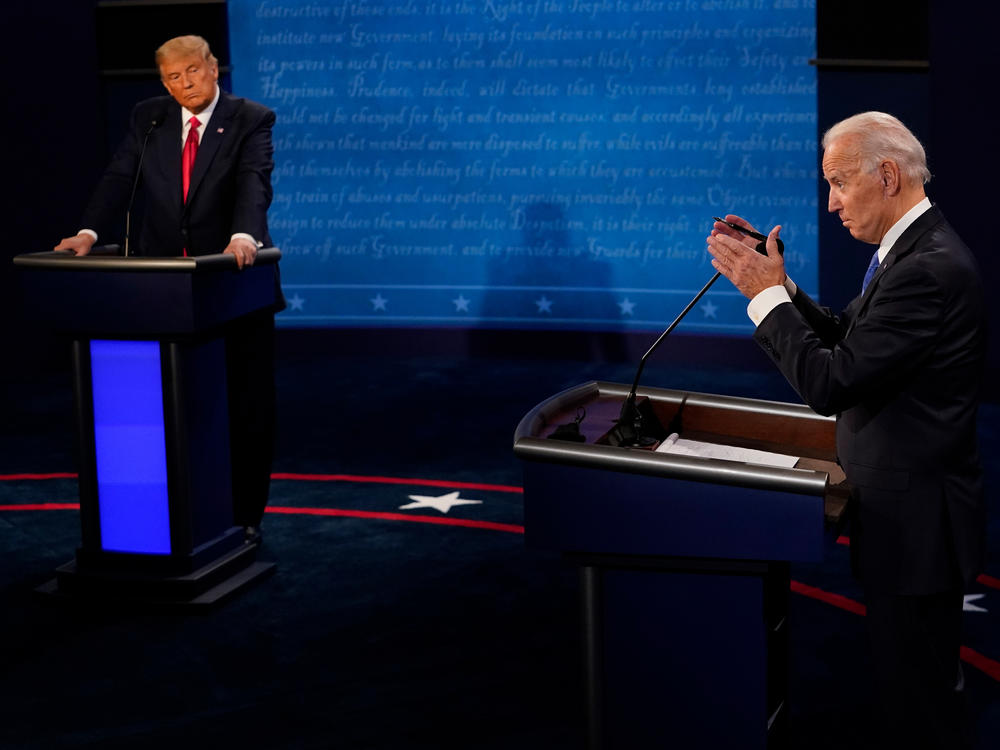

Recent gaffes by Biden and Trump may be signs of normal aging — or may be nothing

Primary Content

Last week, President Biden confused the president of Egypt with the president of Mexico.

In late January, former President Donald Trump appeared to confuse his Republican rival Nikki Haley with Rep. Nancy Pelosi, a Democrat.

The lapses prompted lots of amateur speculation about the mental fitness of each man.

But dementia experts say such slips, on their own, are no cause for concern.

"We've all had them," says Dr. Zaldy Tan, who directs the Memory and Healthy Aging Program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. "It's just that we are not public figures and therefore this is not as noticeable or blown up."

Also, memory lapses become more common with age, even in people whose brains are perfectly healthy.

The temporary inability to remember names, in particular, "is very common as we get older," says Dr. Sharon Sha, a clinical professor of neurology at Stanford University.

Cognitive changes are often associated with diseases like Alzheimer's and other forms of dementia. But all brains lose a step or two with age.

"Even the so-called successful agers, if you measure their cognitive performance, you will see certain changes compared to their baseline," Tan says.

A slower brain

One reason for the decline is a decrease in the speed at which the brain processes information. Slower processing means a person may take longer to respond to a question or make a decision.

That may be a problem for a race car driver or an airline pilot, Tan says. But it's less likely to make a difference to someone who is doing "an executive-level job, where there is a lot of support and a lot more time to do planning and decision making."

Another cognitive change associated with age involves working memory, which allows us to keep in mind a password or phone number for a few seconds or minutes.

A typical person in their 20s might be able to reliably hold seven digits in working memory, Sha says. "As we age, that might diminish to something like six digits, but not zero."

A healthy brain typically retains its ability to learn and store information. But in many older people, the brain's ability to quickly retrieve that information becomes less reliable.

"Trying to remember that name of the restaurant that they were in last week or the name of the person that they met for coffee, that is not in itself a sign of dementia," Tan says, "but it's a sign of cognitive aging."

A glitch or a problem?

Alzheimer's and other forms of dementia become more common with each passing decade. An estimated 40% of people between 80 and 85 have either dementia, which makes independent living difficult, or what's known as mild cognitive impairment.

But diagnosing those conditions requires more than an hour of testing and a thorough history of someone's life, Tan says, not just watching a few seconds of a press conference.

"Some people are reading too much into little snippets of interviews without really knowing what's going on behind the scenes," he says.

Part of the process of diagnosing a brain problem is ruling out other factors.

"We often ask about sleep because that can impair memory," Sha says. "We ask about depression and anxiety, we ask about medication."

It's also critical to measure a person's current cognitive performance against their performance earlier in life, Sha says. A retired professor, for example, may do well on cognitive tests despite a significant mental decline.

Assessing a president

During his presidency, Donald Trump said that he "aced" a test called the Montreal Cognitive Assessment or MoCA. But Sha says that's a 10-minute screening test designed to flag major deficits, not an in-depth look at cognitive function.

"It's a great screening test," Sha says. "But for a president, you would kind of expect that [their score] should be perfect."

Both Sha and Tan agree that voters should consider the benefits of an older brain when considering presidential candidates.

"As you get older, you have more experience, more control [over] your emotions," Tan says. So it's important to not only look at a candidate's cognitive abilities, he says, but also "their wisdom and the principles that they live by."