Section Branding

Header Content

'All of Us' research project diversifies the storehouse of genetic knowledge

Primary Content

A big federal research project aimed at reducing racial disparities in genetic research has unveiled the program's first major trove of results.

"This is a huge deal," says Dr. Joshua Denny, who runs the All of Us program at the National Institutes of Health. "The sheer quantify of genetic data in a really diverse population for the first time creates a powerful foundation for researchers to make discoveries that will be relevant to everyone."

The goal of the $3.1 billion program is to solve a long-standing problem in genetic research: Most of the people who donate their DNA to help find better genetic tests and precision drugs are white.

"Most research has not been representative of our country or the world," Denny says. "Most research has focused on people of European genetic ancestry or would be self-identified as white. And that means there's a real inequity in past research."

For example, researchers "don't understand how drugs work well in certain populations. We don't understand the causes of disease for many people," Denny says. "Our project is to really correct some of those past inequities so we can really understand how we can improve health for everyone."

But the project has also stirred up debate about whether the program is perpetuating misconceptions about the importance of genetics in health and the validity of race as a biological category.

New genetic variations discovered

Ultimately, the project aims to collect detailed health information from more than 1 million people in the U.S., including samples of their DNA.

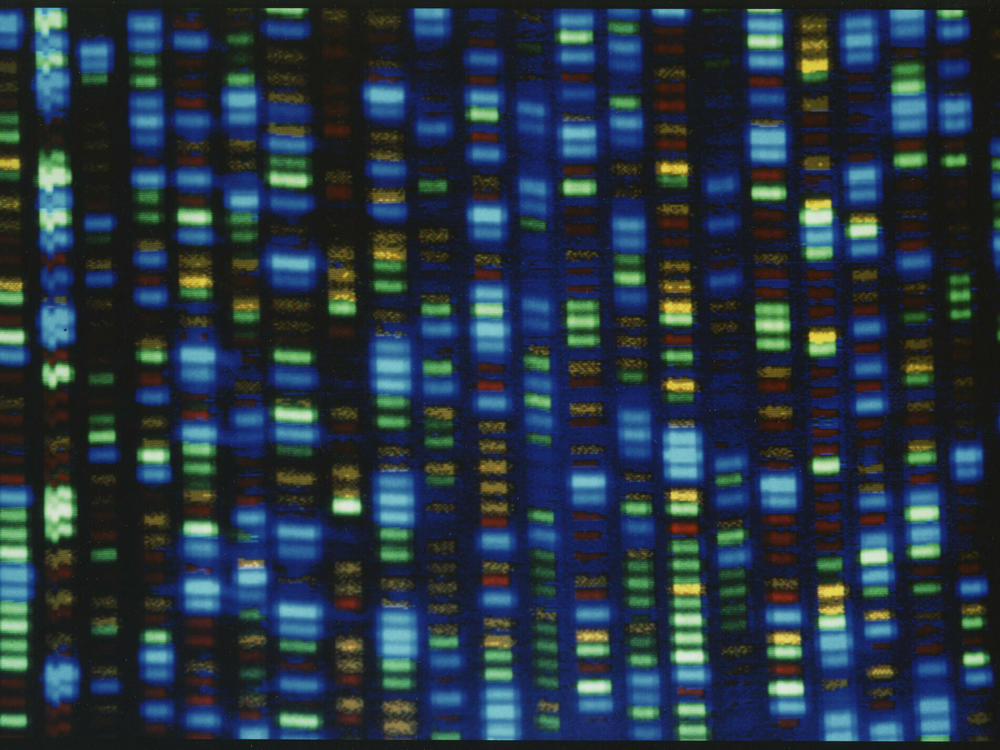

In a series of papers published in February in the journals Nature, Nature Medicine, and Communications Biology, the program released the genetic sequences from 245,000 volunteers and some analysis of those data.

"What's really exciting about this is that nearly half of those participants are of diverse race or ethnicity," Denny says, adding that researchers found a wealth of genetic diversity.

"We found more than a billion genetic points of variation in those genomes; 275 million variants that we found have never been seen before," Denny says.

"Most of that variation won't have an impact on health. But some of it will. And we will have the power to start uncovering those differences about health that will be relevant really maybe for the first time to all populations," he says, including new genetic variations that play a role in the risk for diabetes.

But one concern is that this kind of research may contribute to a misleading idea that genetics is a major factor — maybe even the most important factor — in health, critics say.

"Any effort to combat inequality and health disparities in society, I think, is a good one," says James Tabery, a bioethicist at the University of Utah. "But when we're talking about health disparities — whether it's black babies at two or more times the risk of infant mortality than white babies, or sky-high rates of diabetes in indigenous communities, higher rates of asthma in Hispanic communities — we know where the causes of those problem are. And those are in our environment, not in our genomes."

Race is a social construct, not a genetic one

Some also worry that instead of helping alleviate racial and ethnic disparities, the project could backfire — by inadvertently reinforcing the false idea that racial differences are based on genetics. In fact, race is a social category, not a biological one.

"If you put forward the idea that different racial groups need their own genetics projects in order to understand their biology you've basically accepted one of the tenants of scientific racism — that races are sufficiently genetically distinct from each other as to be distinct biological entities," says Michael Eisen, a professor of molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley. "The project itself is, I think, unintentionally but nonetheless really bolstering one of the false tenants of scientific racism."

While Nathaniel Comfort, a medical historian at Johns Hopkins, supports the All of Us program, he also worries it could give misconceptions about genetic differences between races "the cultural authority of science."

Denny disputes those criticisms. He notes the program is collecting detailed non-genetic data too.

"It really is about lifestyle, the environment, and behaviors, as well as genetics," Denny says. "It's about ZIP code and genetic code — and all the factors that go in between."

And while genes don't explain all health problems, genetic variations associated with a person's race can play an important role worth exploring equally, he says.

"Having diverse population is really important because genetic variations do differ by population," Denny says. "If we don't look at everyone, we won't understand how to treat well any individual in front of us."