Section Branding

Header Content

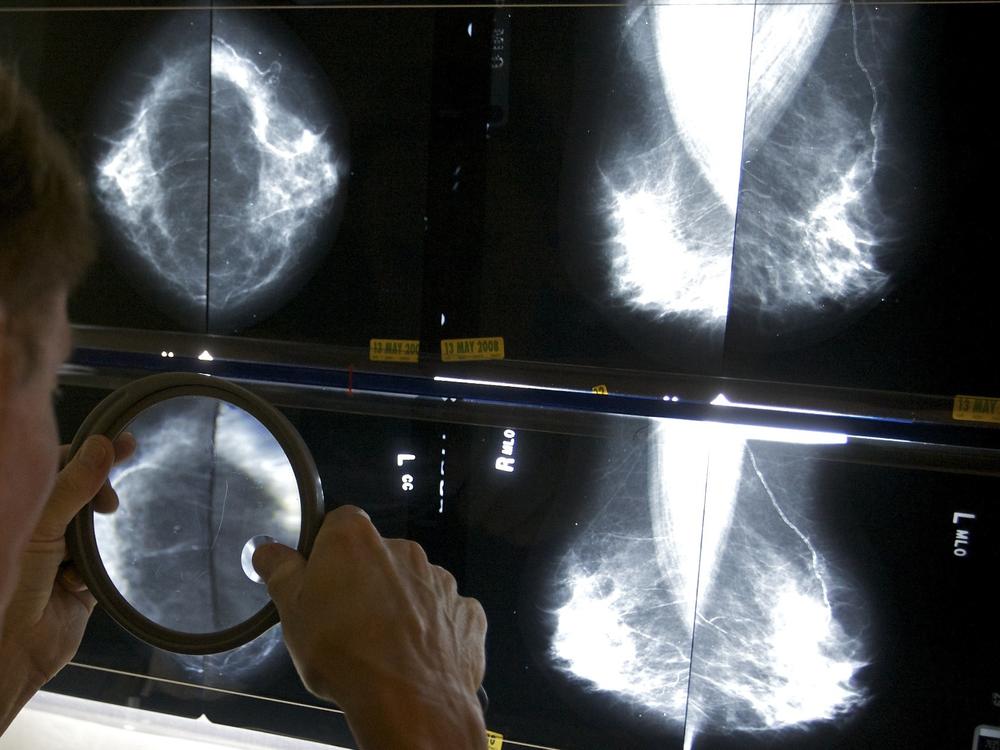

Mammograms will better explain what it means to have dense breasts

Primary Content

Nearly half of women over 40 have what doctors consider dense breast tissue, which increases their risk of cancer, yet until now, few are told what their diagnosis might mean, or what they should do. But as of this week, patients with dense breasts will get more guidance after a mammogram about their risks, thanks to a new requirement adopted by the federal Food and Drug Administration this week.

The breast is made up of things like glands and fibrous connective tissue. The more of that — as opposed to fat — is in the breast, the denser it is, and the higher the risk of developing cancer.

“We know through research that women with dense breasts are 4 to 5 times more likely to get breast cancer than women without dense breasts,” says Molly Guthrie, vice president of policy and advocacy at the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation.

She says not only does it make developing tumors more likely, denser tissue also makes it hard to detect tumors on those black-and-white mammogram images. Therefore, someone with risk factors, in addition to dense breasts, may benefit from additional ultrasound or MRI screening.

That’s why understanding breast density is important.

For the past decade, Guthrie’s group has been campaigning for breast density to be both included on mammograms, as well as better explained.

Over 35 states and the District of Columbia already require some kind of assessment of breast density. But Guthrie says often those reports came with confusing information, or none at all: “It would say, ‘You have dense breasts,’ but nothing else – so they had no idea what to do, what it meant for them, and just created a lot of confusion and anxiety.”

The FDA’s new rules are designed to simplify the medical language so it is understandable to those with low literacy, to explain what breast density means, and to give clearer guidance about consulting a doctor for more information.

It will, for example, identify four levels of breast density, with a uniform explanation of the risks associated with each one. Notices sent to patients will say things like: “In some people with dense tissue, other imaging tests in addition to a mammogram may help find cancers.”

Guthrie says she hopes patients will then discuss with their doctors whether an MRI or ultrasound might be recommended, for example.

While regular mammograms are required to be covered with no out-of-pocket costs by all health plans, women who need follow-up screenings may face out-of-pocket costs, Guthrie notes. And that might turn patients off. That, she says, is the next necessary policy change.