Section Branding

Header Content

'Regarding Paul R. Williams' Honors Legacy Of LA's Barrier-Breaking Black Architect

Primary Content

Photographer Janna Ireland aims to capture intimacy and relationships in her work, which she says focuses primarily on Black life in America.

For the Los Angeles-based photographer, that has included photographing staged scenes as well as self-portraits and portraits of her family — including, most recently, of her two sons during the pandemic.

"In my work, I'm happy when all different kinds of people appreciate it, but I feel as though I'm making it for Black people," she says.

In a new book, Ireland turns her lens outward, to showcase the legacy of barrier-breaking architect Paul R. Williams, and introduce his work to a larger audience.

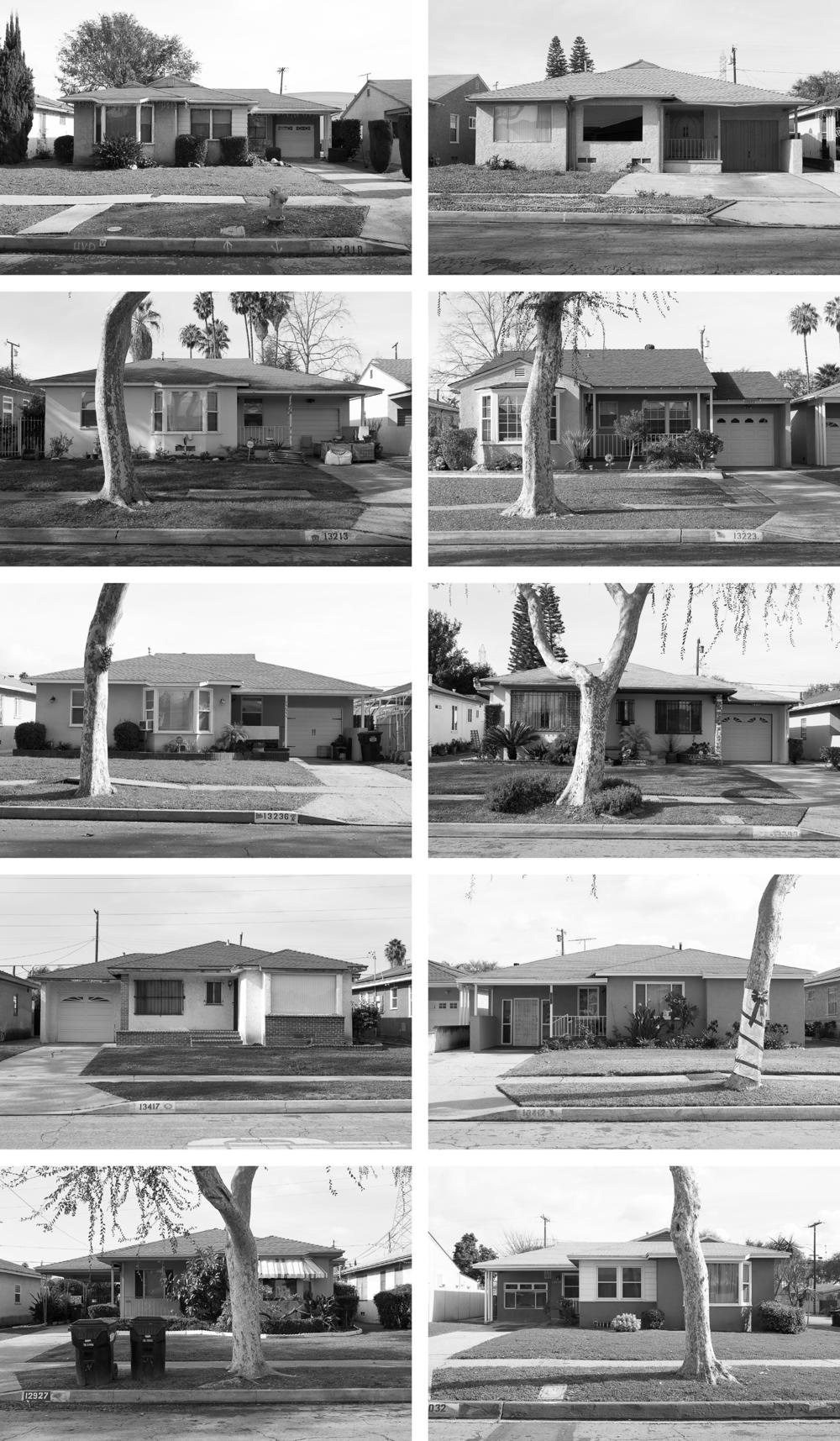

Regarding Paul R. Williams: A Photographer's View is a collection of 280 photographs by Ireland that celebrate the career of the first Black licensed architect west of the Mississippi. His work helped shape the landscape of Los Angeles and brought good design within reach of all, regardless of race.

Architecture as a subject wasn't necessarily a natural transition for Ireland, whose past work has primarily been portraiture. But after learning about Williams' life, Ireland was drawn to telling his story.

"When I take a portrait of myself, I'm making it for a girl who is like I was and needs to see herself reflected in art," Ireland says. "And the Paul R. Williams work is an extension of that process."

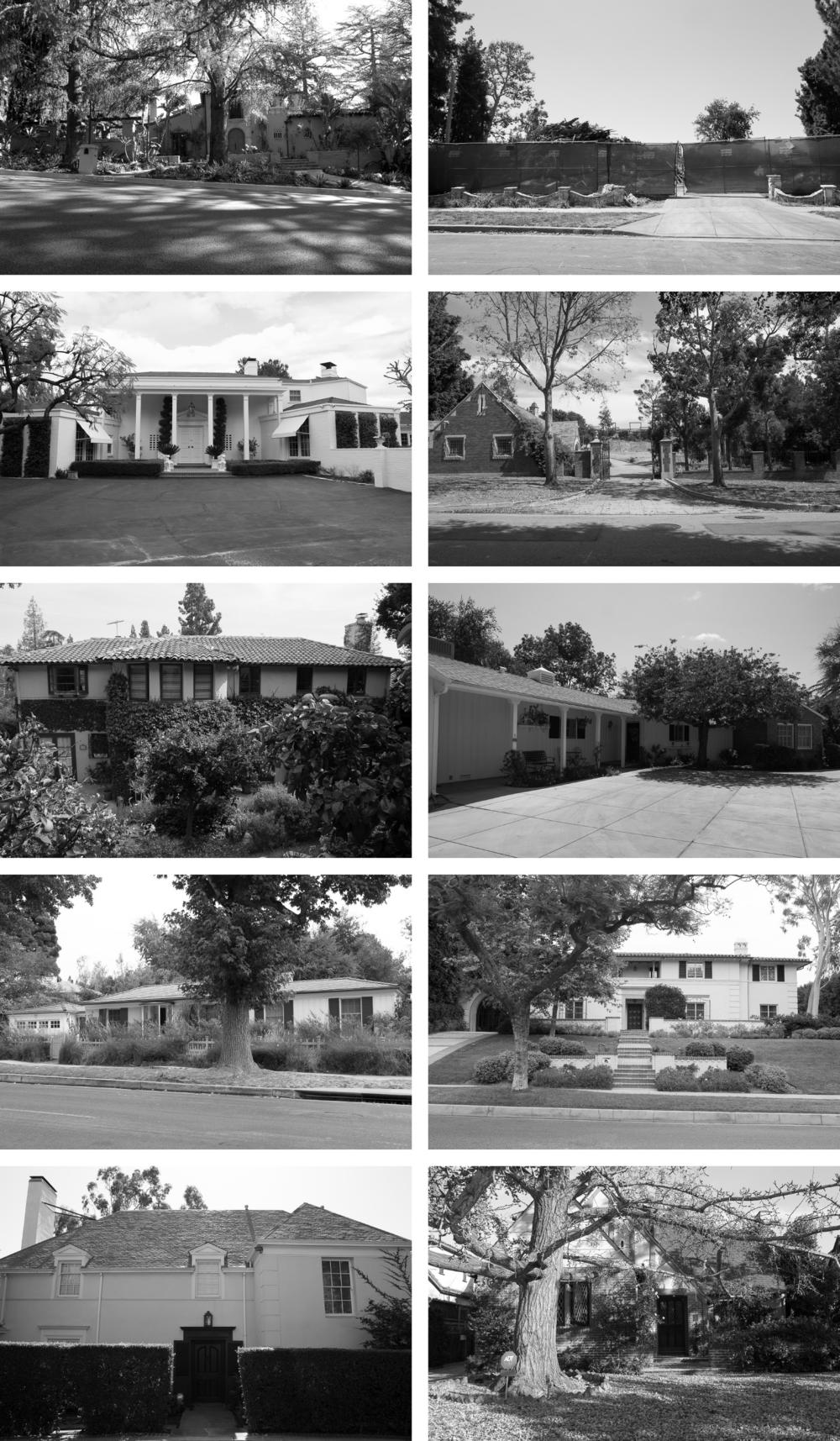

Williams was prolific and his repertoire is vast in both style and quantity, creating some 3,000 buildings before his death in 1980. He's often remembered as an "architect to the stars," creating opulent mansions for the likes of Lucille Ball and Frank Sinatra.

But he also helped design iconic public and commercial buildings: the modern Los Angeles County Mosk Courthouse, the historic Spanish-colonial style YMCA building in downtown LA, and even parts of Los Angeles International Airport.

In 1923, he became the first Black member of the American Institute of Architects — one of many "firsts" in his long career.

After he established himself, Ireland says, Williams chose projects that would uplift the Black community. He designed everything from banks and churches in predominantly Black neighborhoods, to affordable housing for Black veterans returning from World War II. Ireland says he believed that "good design wasn't just for the rich," that it was for everyone, regardless of race or class.

Ireland first learned about Williams' work about four years ago, when LA architect Barbara Bestor asked Ireland to photograph a handful of Williams' projects.

And as she researched his life, Ireland says she discovered parallels with her own experiences as a Black artist.

Born in 1894, Paul R. Williams knew at a young age that he wanted to be an architect. But when Williams shared his dreams with a white teacher, he was told that Black people would never be able to afford him and white people would never hire him.

Nearly a century later, in another classroom, Ireland sat dreaming about being a photographer. But when she told a teacher — also white — that she hoped to attend New York University to study photography, he told her that it "wasn't a place for people from humble beginnings."

"I thought a lot about what he meant in the years since," Ireland says, "and whether he meant that it wasn't a place for me because I'm Black."

His comments affected her deeply; she became depressed and nearly didn't apply.

But eventually, she earned her dream degree from NYU — and, later, an MFA from UCLA.

As she researched Williams, Ireland learned of the other ways race had an impact on his career: how he learned to draw upside-down so that his clients, often white, would not have to sit beside him, and how that for much of his career, Williams designed homes in neighborhoods he couldn't live in himself because of racially restrictive covenants tied to property deeds across swaths of Los Angeles at the time.

Ireland says she thought a lot about the "indignity" Williams had to endure throughout his life. "These stories made me angry on his behalf," she says.

Fueled by that anger and a desire to shine a light on just how deep Williams' influence has been, Ireland continued to photograph his work, culminating in the new book.

It's not an encyclopedic guide to Williams' designs, Ireland says, but her interpretation of his work.

Ireland says she hopes that her desire to capture "relationships between people and relationships between a subject and the camera"is visible in the way she chose to photograph Williams' buildings.

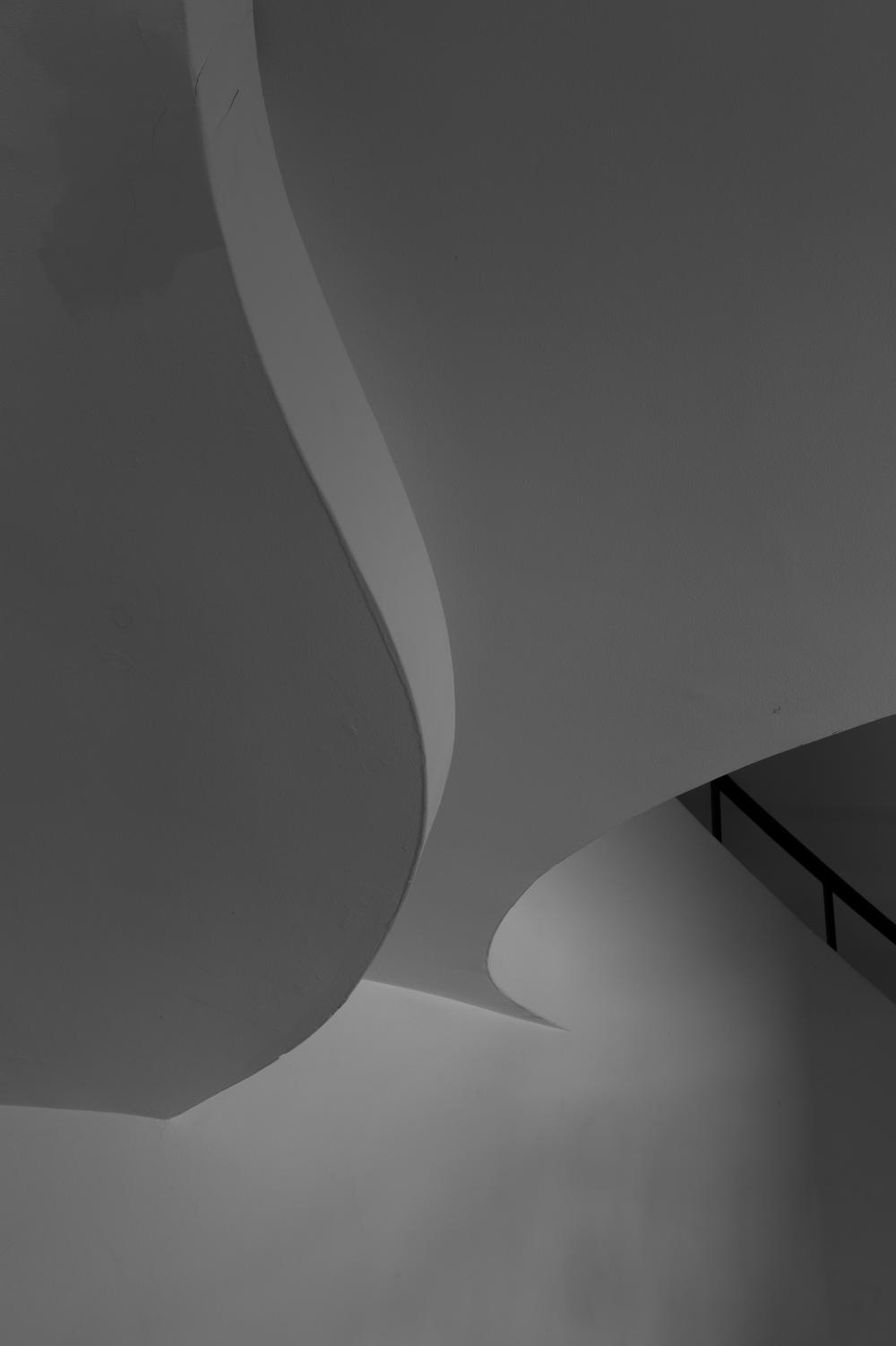

"Most architectural photography is about giving an overview of how a space is supposed to function, but it doesn't give you insight into the small details," Ireland says. "When I talk about intimacy in relation to the Paul R. Williams work, it's about these close-ups you would see walking around a space."

For instance, many of Ireland's photographs of Williams' work feature curving lines at the edge of a ceiling or of a shadow falling on the corner of a church building.

While Williams is known for his use of curves to create intimate environments or elaborate stairwells to make a space feel grand — perhaps what's most notable about his work is that he wasn't tied to a particular "signature" style.

Instead, he met the needs of a range of clients, from those commissioning mansions to those who sought affordable housing — all while maintaining high standards of quality design. Ireland hypothesizes that Williams' versatility was borne out of necessity because he had to be more dexterous than white contemporaries.

Ireland says Regarding Paul R. Williams isn't the end of her quest to get to know the architect she says is "criminally under recognized and underappreciated."

An archive of Williams' drawings and notes, thought to be lost to a fire 28 years ago, was recently rediscovered and will be available to the public. That, Ireland says, will open up new doors. She says she plans to continue taking photos of Williams' buildings, but doesn't know exactly what form the future work will take.

"I feel as though the part of the project that's in the book is finished," she says, "and maybe it's time to start another chapter."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Correction

In a previous audio version of this story, we incorrectly said that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1948 that racially restrictive covenants were unconstitutional. In fact, the Supreme Court ruled that enforcement of racially restrictive covenants by courts was unconstitutional.

Bottom Content