Section Branding

Header Content

Vanessa Leroy Once Used Daydreaming To Escape. Now, It's The Heart Of Her Photography

Primary Content

In November 2014, Vanessa Leroy was out photographing protests against police brutality in Boston. Three months earlier, a police officer in Ferguson, Mo., had shot and killed Michael Brown. In Boston and countless other cities across the nation, thousands were joining together in protest.

"That was really the first time where I was using my camera to capture an event such as this and the rage that everyone was feeling," says Leroy. "I feel like that was really a pivotal point for me, when it comes to realizing why I wanted to pursue photography."

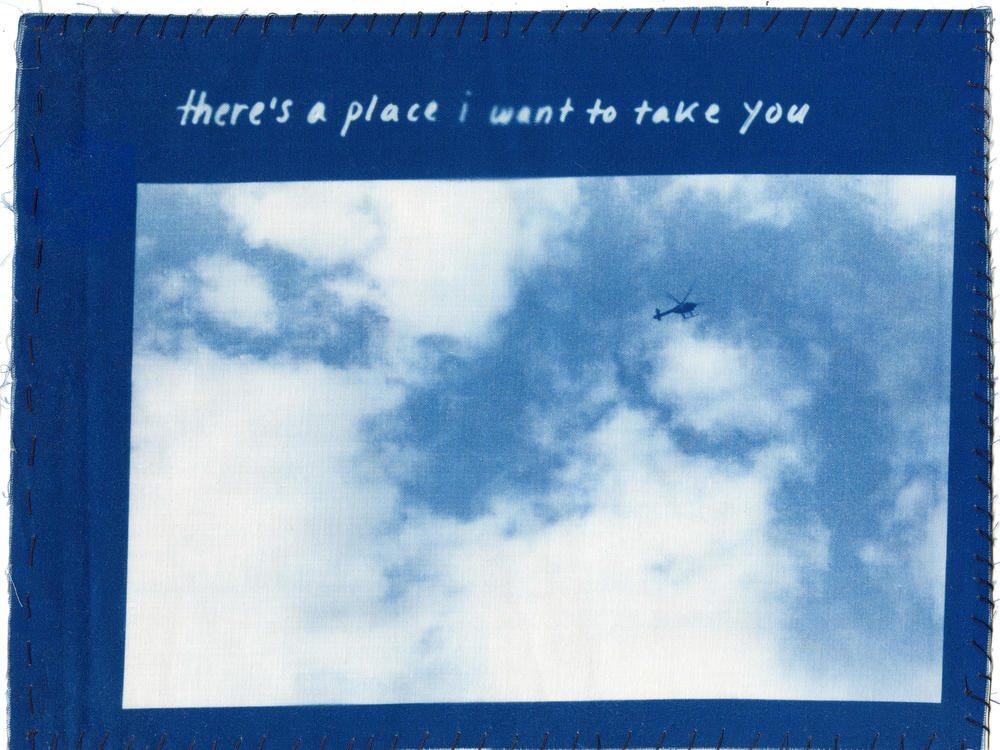

Leroy says the protest was fraught with all kinds of emotions — anger, frustration, sorrow. But the image that endures for her is one that offers another way to think about the pain of that day. It's a picture of a helicopter, high above the demonstrators, flying through a blue Boston sky.

"I took it out of the context that it was originally in to make it feel you're entering into this dream space where you're about to navigate all of these memories and past experiences," she says.

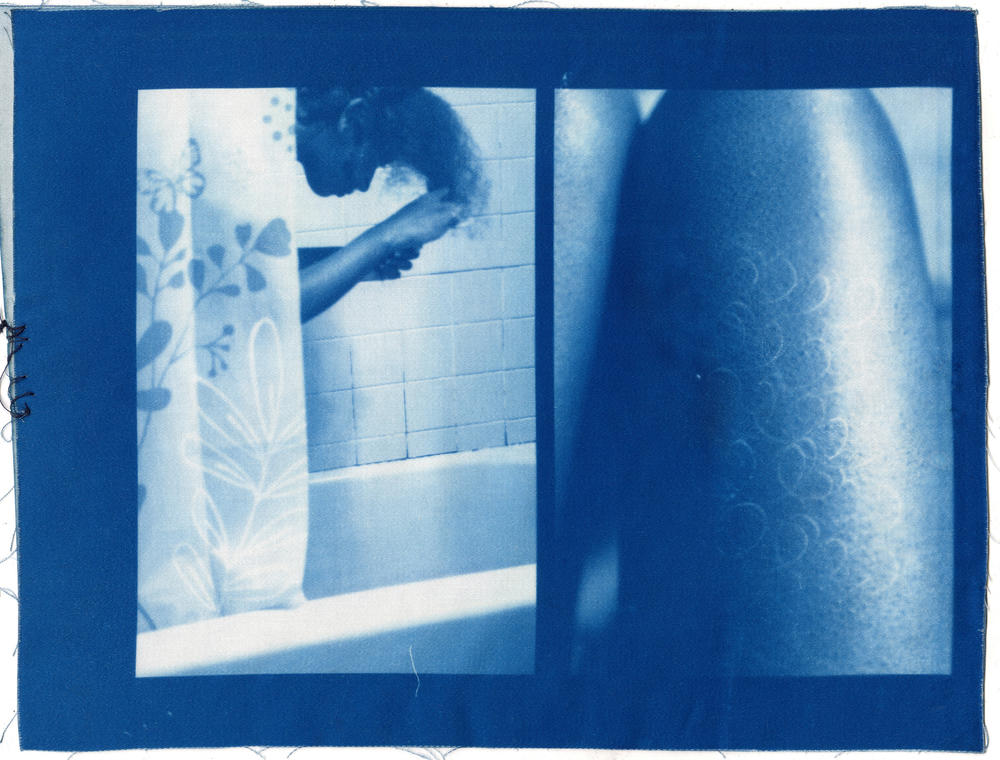

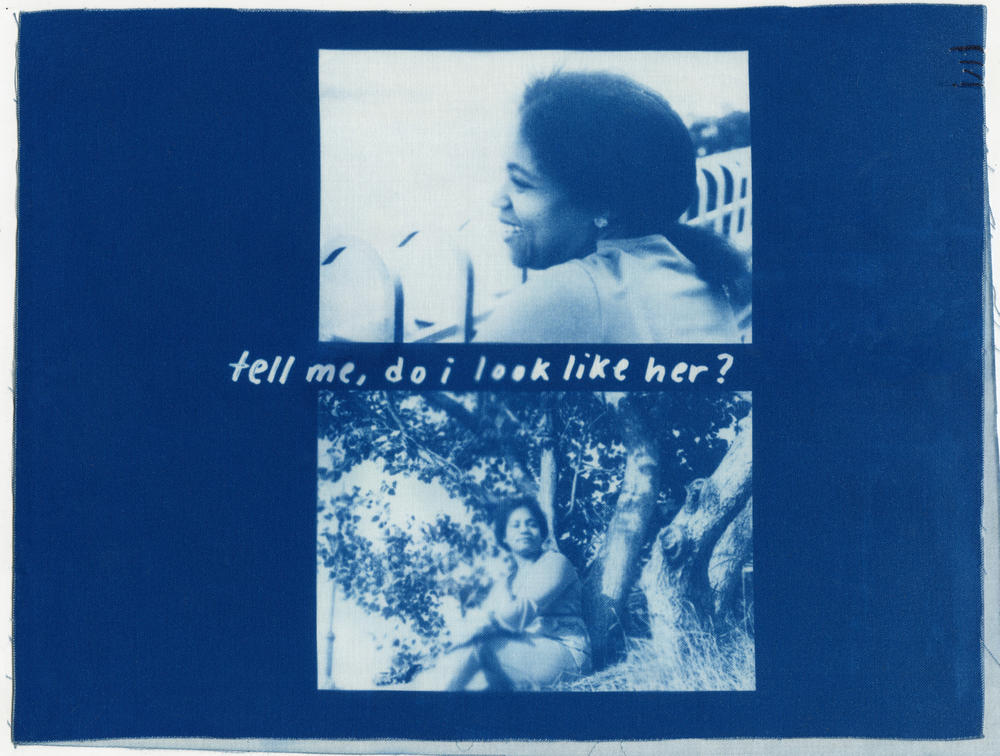

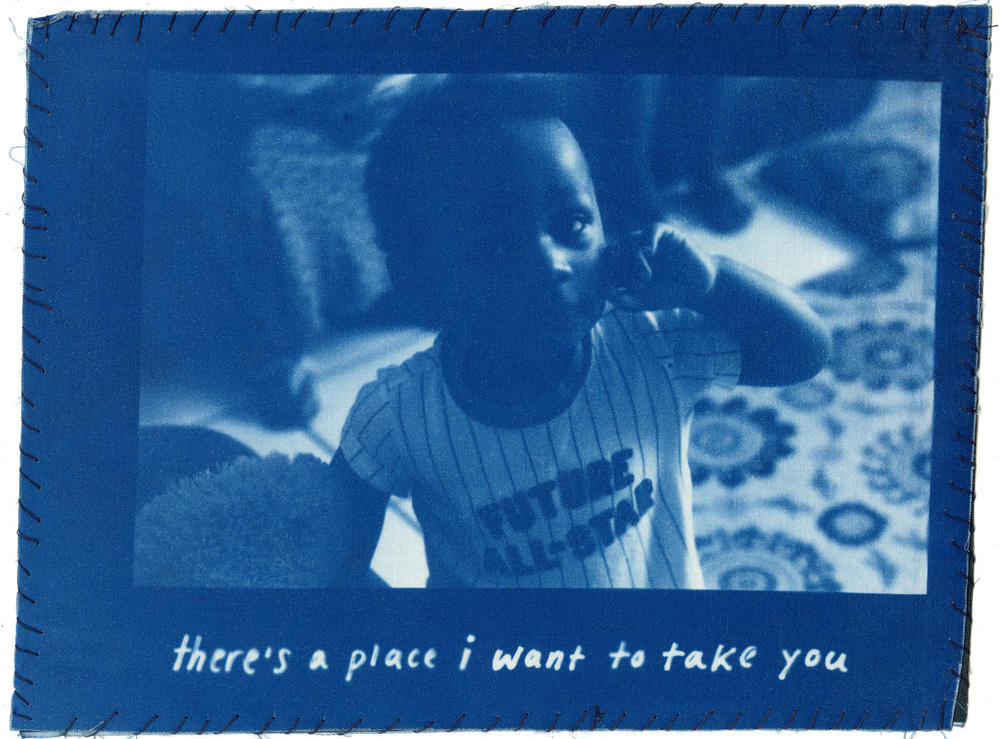

The image is part of a new book, titled there's a place i want to take you, which Leroy describes as a map of her experience of Black childhood. The autobiographical handmade book leans on a technique called the cyanotype process — known best for the distinctive cyan blue tones it produces.

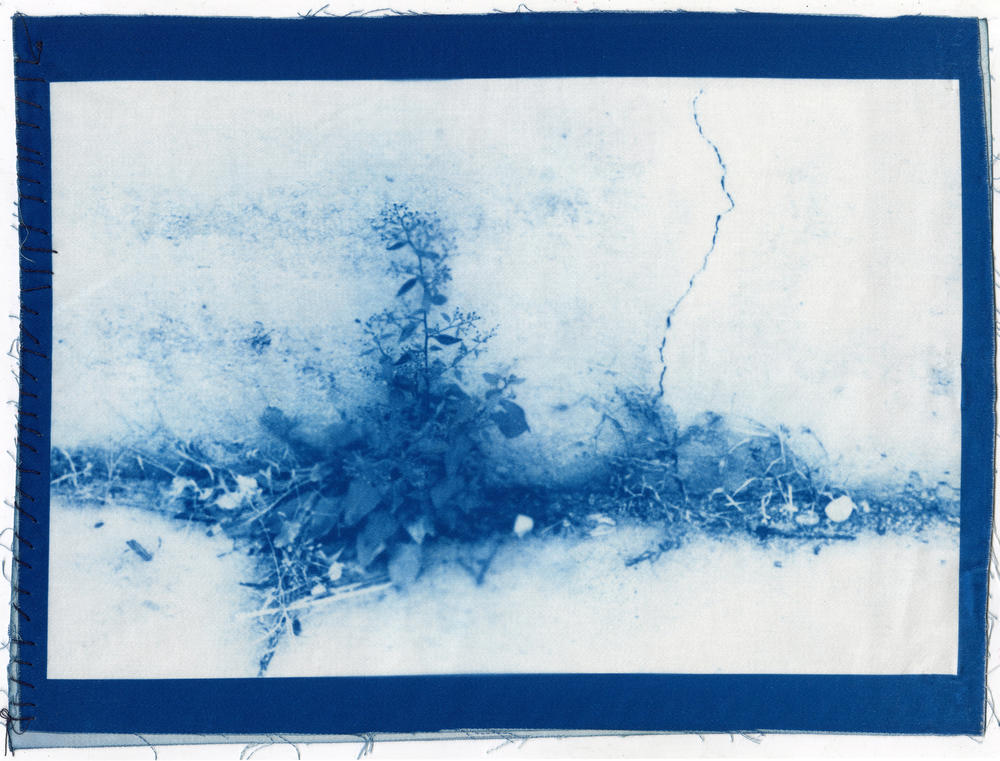

Leroy says she draws inspiration for her work from artists who create worlds — artists like Lorna Simpson, Ana Mendieta and the Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki. She says she is particularly intrigued by the meeting of nature and manmade elements — an interest that is present throughout her work.

"I relate heavily to the organic world," she says. "Seeing nature emerging from man-made structures resonates with me."

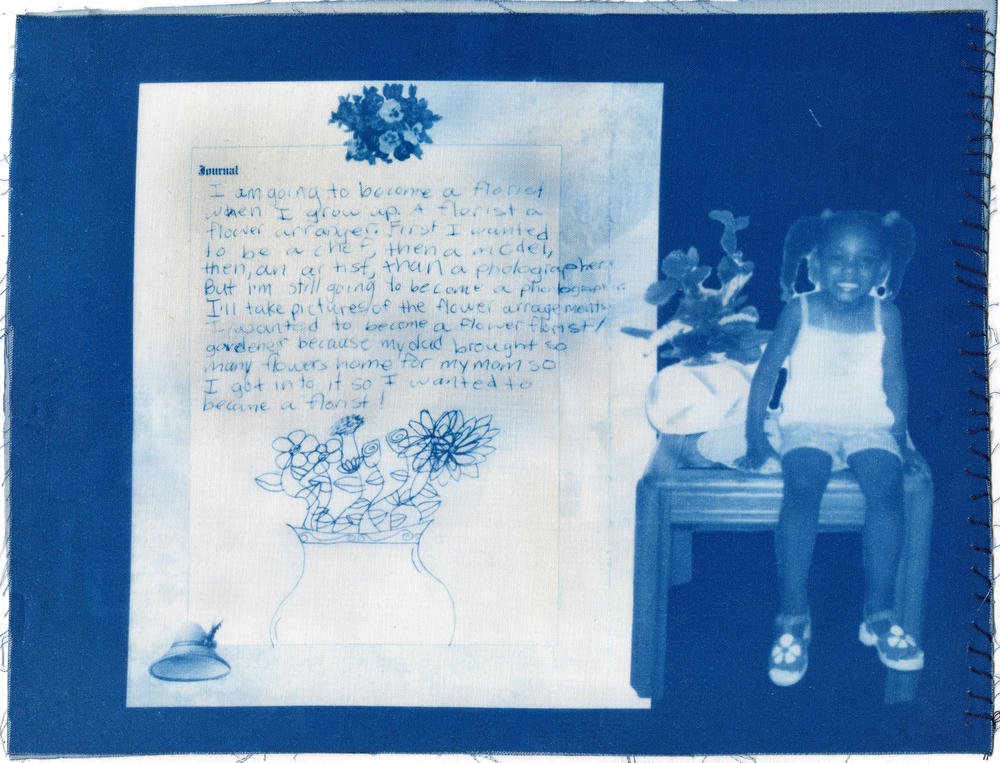

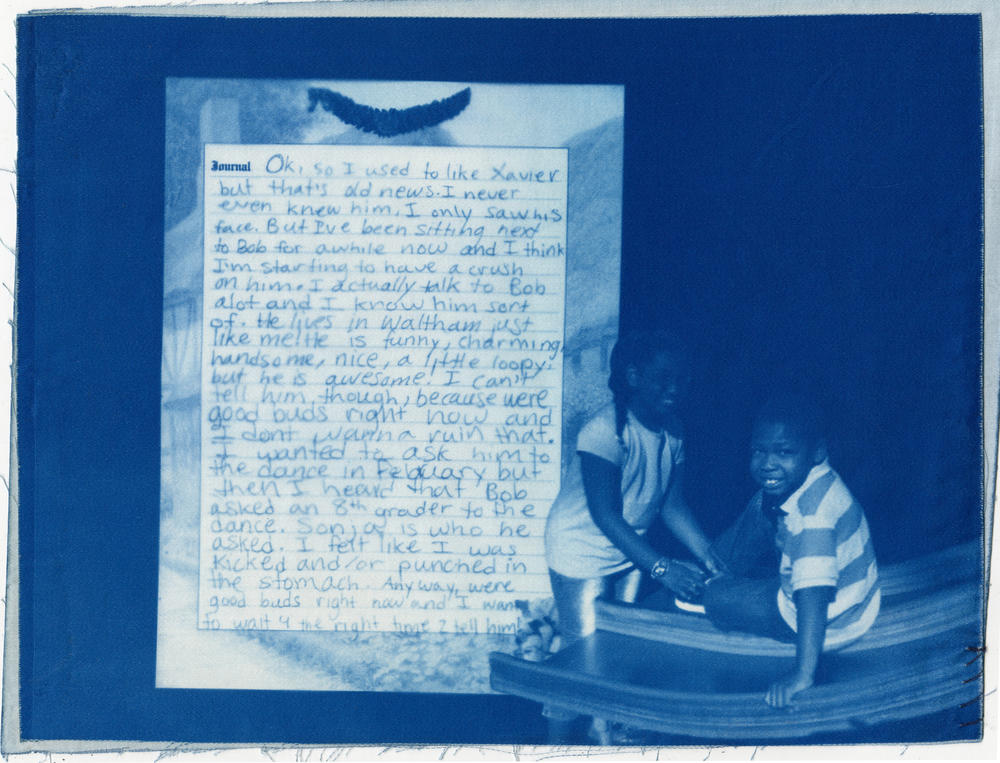

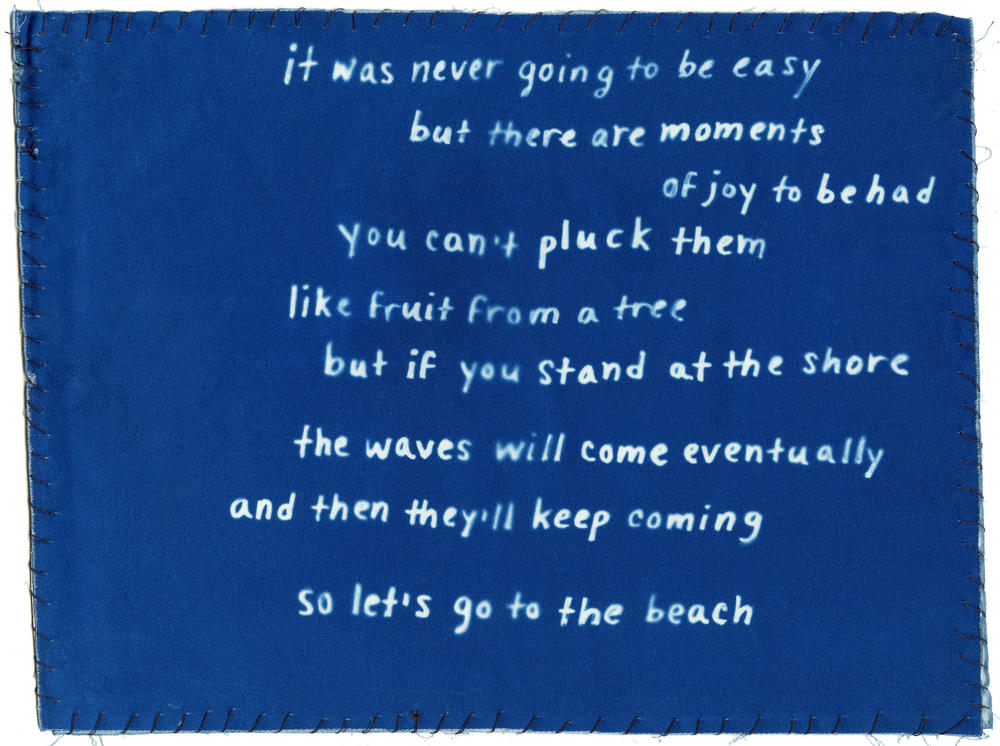

Her book is a blend of images, text and illustration — all recontextualized to create a dreamlike timeline of the author's memories.

"There isn't a lot of space for dreaming in an oppressive world," says Leroy, "so I use photography as a tool to create a space where I can freely navigate the various facets of my life, experience and identity."

Leroy, 24, says that ever since she was a child, she's used daydreaming as a form of escapism. It was a form of survival, but it also meant that as she grew up, "I rarely spent time trying to understand and accept myself."

"Into adolescence, my mental health suffered as I began to see life through a fog," says Leroy. "This was compounded by racism I faced and witnessed in the world. In the seventh grade as I walked home alone from school one day, I was called the N-word for the first time by a group of white men that screamed and spat while they drove past me in their red pick-up truck."

In addition to the racism she experienced, Leroy says she also faced adversity from within. While blocking out her parents divorce, she struggled with disliking herself, both internally and externally. She would dream about being different than she was.

For a long time, Leroy explains, she didn't think her voice was worthy or wanted.

"From the viewpoint of a black woman," she says, "I know oppression to be when your humanity is structurally infringed upon. We're living in this white supremacist, capitalist nation and anyone who dares to dream anything bigger than where they currently are, is discouraged because of the way that society currently functions. So that really disempowers you."

The book is a reflection on the role that dreaming has played in her in life. She says it's meant not only for herself, but also to her younger brothers, ages 21 and 5.

"I'm speaking to my younger self, or anyone else who is open to receiving the message that there's a place that I want to take you, and it's a place where you can finally feel free. A place where you feel less pain than you used to, a place you no longer feel weighed down by what has brought you to those places before."

These days, Leroy says her dream space has a different purpose than before.

"Now whenever I enter that dream space, it's more of a meditative space — less of a form of escapism and more of a form of grounding myself and remaining present ... sitting with myself instead of sitting with this character of myself that was leagues away from who I actually am."

"I'm now at the center of these dreams in my own form. I no longer compartmentalize my emotions, create a facade of strength, or suppress my own voice."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content