Section Branding

Header Content

A Photographer Saw An Arkansas Town Fading. His New Book Keeps Its Stories Alive

Primary Content

The town of Earle, Ark., is disappearing.

Or at least, that's what it looked like to photographer Eugene Richards.

In the postscript of his new book, the day i was born, Richards writes about returning to the area in 2019 after years away and noticing the overwhelming presence of absence:

No men and women picking cotton. No old folks on the porch staring out at you. No children running and jumping around. The sharecropper shacks that were here 50 years ago have vanished. Once there were four or five of them every couple of miles — tin roofs, plastic sheeting over the windows, front yards rutted with tire tracks, littered with rusted-out cars, bed springs, things that once meant a lot to someone, but didn't any longer.

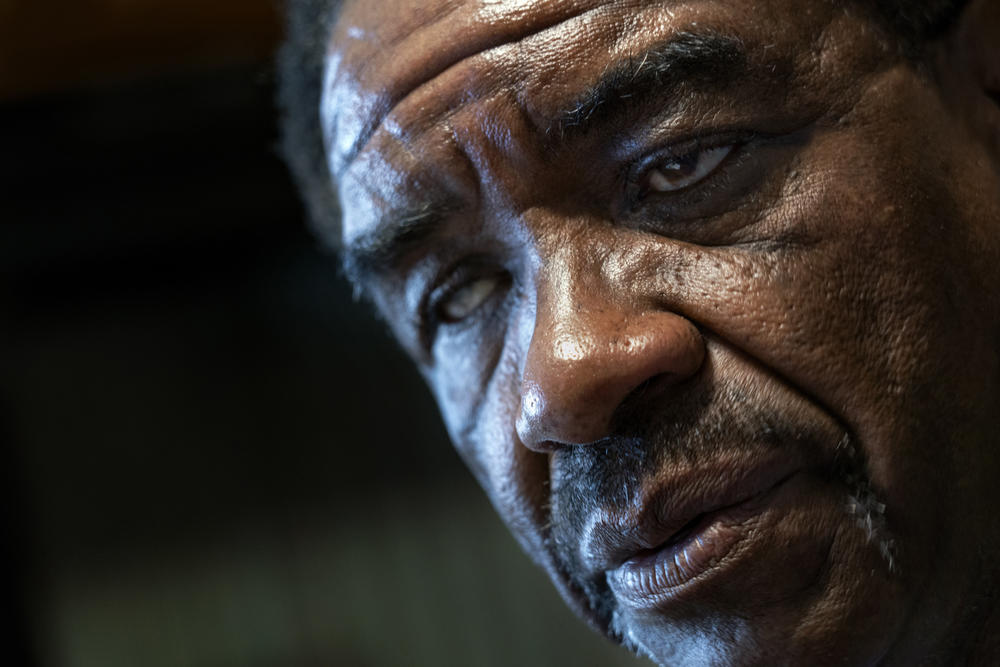

In the book, that epilogue is the only time we hear Richards' voice. The rest of the text to accompany his photos are the first-hand accounts of six people, all of whom are Black, over 50 and most have lived in Earle for much of their lives: Joseph Perry, Jr., Stacy Abram, Lovell Davis, Jackie Greer, Timothy Way and Jessie Mae Maples. The photos capture daily life for these six as well as other Earle residents, in addition to the stark and impoverished landscape of the Delta.

Though the town may look to Richards like it's fading, its history is very much alive. In preserving them in the day i was born, Richards ensures that these stories — of racism and segregation, of voter suppression, of homophobia, of poverty, of gun violence and police brutality — won't also disappear.

Richards' relationship with the Arkansas Delta goes back decades. He first arrived in the Delta in 1969 as a VISTA volunteer. VISTA, which stands for Volunteers in Service to America, was designed to be the domestic version of the Peace Corps. Richards, who is white, spent three years in the Delta working in predominantly Black communities as a social worker and a photographer, and also running a small community newspaper. He looks back on that time not in a self-congratulatory way, but as a matter of course. In an interview with NPR, he remembered, "because of the Vietnam War happening and Dr. King happening, and the assassinations all happening all the time, you took the admonitions to get involved quite seriously. And that was it. So it isn't something that you think about later. It became kind of natural."

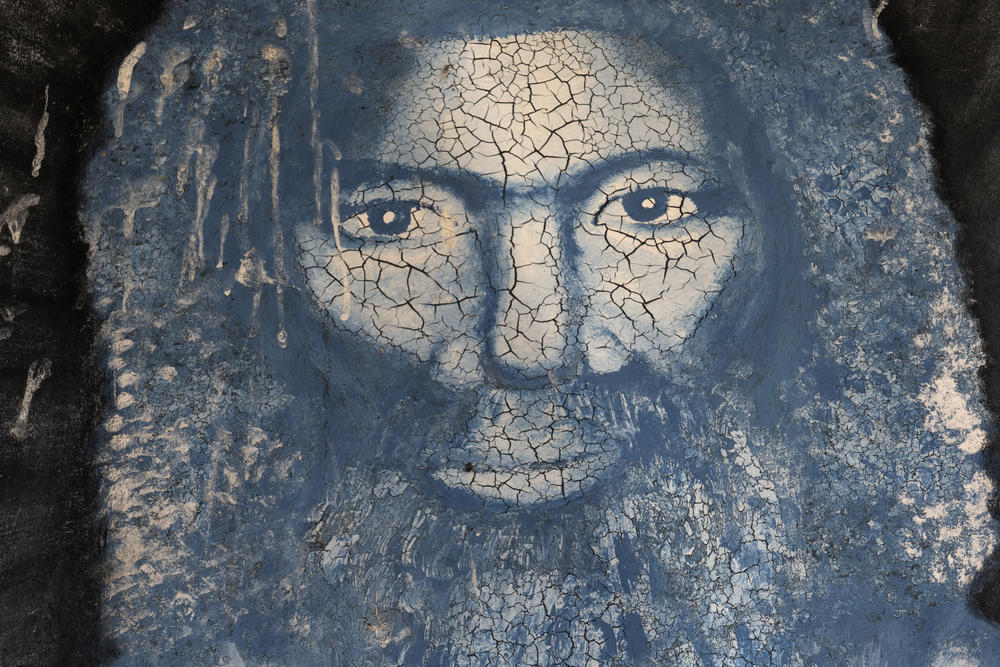

the day i was born almost came about as an accident. In 2019 Richards was working on a project about abandoned houses for a large newspaper and went back to the Delta for material. Then, he said, "I drifted over into Earle because I was curious about what the towns look like today that I remembered from a long time ago." Following Main Street, he came to an appliance store covered in paintings of people like Huey P. Newton, Angela Davis, Malcolm X and Tupac Shakur.

When Richards entered the store a couple days later, he was greeted by owner Stacy Abram, and the two struck up a conversation. Richards had a recorder, and he turned it on while Abram told him about a childhood with an imprisoned father, a job as a teenager at the cotton gin and the first days of schools integrating. Soon, Lovell Davis entered the store and told Richards about growing up as best friends with Abram, about going to school hungry, about his own time in prison after robbing a bank. Timothy Way, an eccentric gay man who painted the freedom fighter portraits on the store, also showed up and shared his life stories with Richards. "So it wasn't like I searched people out," Richards said. "I never thought about any kind of book at the time. But the storytelling was so direct and compelling."

When he returned home to New York City and turned in the photographs and the interviews to the newspaper he'd been working for, he never heard any response. "You have to create your own narrative when you don't hear from anybody," Richards said. He figured his dispatch from Earle had fallen flat with his editors. "So the narrative was everything sucked, and I didn't think it did. I knew there were stories there."

He decided to make a book of the work. "I kind of went overboard," he said. "It could've been a tiny book. But the [subjects] deserve a really nice book."

The stories are all too familiar today, mirroring incidents that have sparked national conversations and worldwide demonstrations. "It's not only this town, it's the world." says Lovell Davis in the book's epigraph.

In 1970, a group of about 150 Black residents — including Jackie Greer and Jessie Mae Maples — marched to city hall to protest the continued segregation of the schools. A group of about 30 white people showed up, supported by local police, with clubs and guns and descended on the protestors. They fired shots, grazing Greer's head and critically injuring Maples. No charges were ever filed against the white assailants, but Greer's husband — the Rev. Ezra Greer, who was beaten by the mob and suffered a broken arm — was charged with inciting a riot.

"In these little towns, people rose up without any support," Richards said. "I mean, nobody was coming in from other places. It wasn't like protests now when people come from all over. All these people stood up in their little towns, all by themselves."

"The march, it's mostly forgotten," Greer says later in the book. "Earle is nothing but a little out-of-the-way place that most people haven't heard anything about. We never did really get much news coverage. We're too far from Little Rock. And in Memphis, unless there's a murder, they hardly holler, didn't bother about coming."

the day i was born provides more than just coverage; it's an oral history straight from those who lived through it, and live through it still.

"What people went through before was not at all dissimilar. But how brave they were to be doing it all by themselves," Richards said.

Melody Rowell is a writer and podcast producer living in Kansas City, Mo. You can follow her on Twitter @MelodyRowell.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.