Section Branding

Header Content

The view inside Gaza — from an American citizen who just left

Primary Content

With few journalists on the ground and frequent phone and internet blackouts, it has been hard to get a clear picture of what life is like for people in Gaza.

It is becoming a little more clear now that some foreign nationals have been allowed to cross from Gaza into Egypt. One of them is 65-year-old Qassem Ali.

Ali grew up in the northeast Gaza village of Beit Hanoun and worked as a journalist. He studied in America, and in 1997, got U.S. citizenship.

Over a Zoom call, he told NPR he was visiting his 90-year-old mother in northern Gaza — about two miles from the border with Israel – when, on Oct. 7, Hamas insurgents crossed into Israel, killing more than 1,400 people and taking more than 200 others hostage.

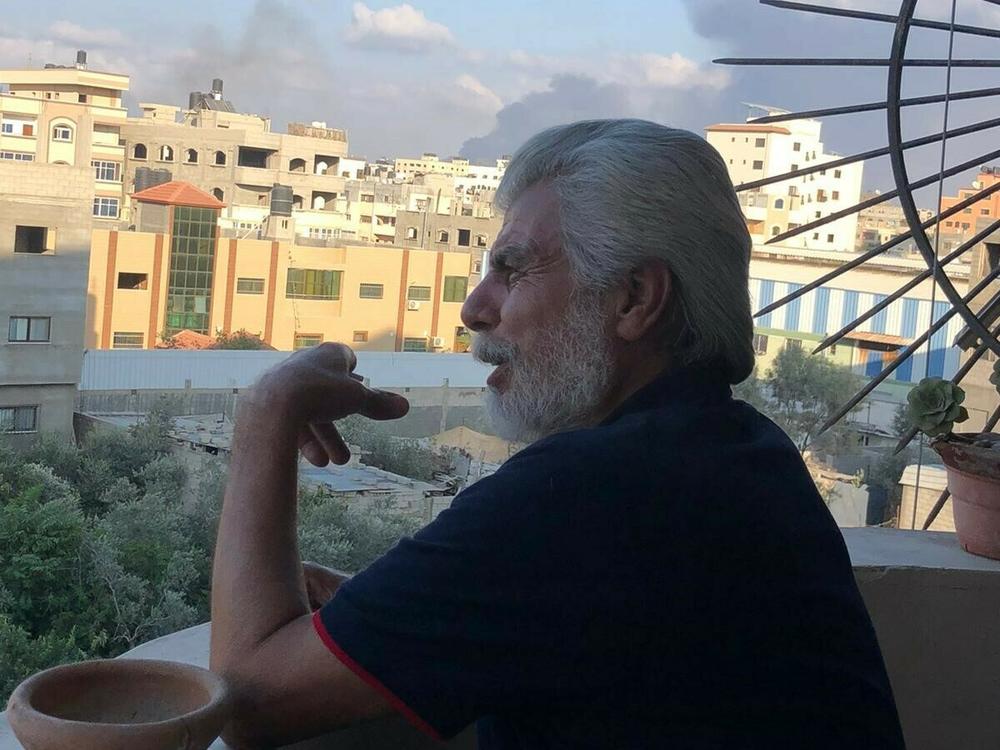

The morning the war began, Ali was on the rooftop garden of his family home.

"I love gardening, so I have a nice rooftop," he said. "I hear the missiles ... and, you know, [as a] former journalist, I start filming."

His video shows a lush garden full of plants. There is a sunrise and the sounds of birds chirping, and then — explosions. One after another. And close.

"I figure it will be serious," Ali recalled. "So I decided to take a shower before the Israelis — I know it's crazy but that's the reality — I took a shower quickly because I don't want to be dying while I'm naked, you know?"

He and his mother fled to his sister's apartment in Gaza City. The missiles from Israel followed them there, so they fled again. The days started to blur together.

"You don't know days, my friend," he said. "You don't know if it's Monday or Friday, all the days are the same. If you ask me now what's the day, I don't know. That's the life of war. Especially this war."

"I have been covering all the wars in Gaza ... but this is different. This is not just a war. This is more than a war."

In the four weeks since the conflict began, more than 10,000 people have died in Gaza, according to the Ministry of Health.

Despite all this — despite the violence, despite not knowing what day it is, despite being a U.S. citizen — Ali said he didn't think about trying to leave. Not at first.

"I wanted to stay with my sister and my mother," he said. But then he managed to talk to his 13-year-old daughter Nadia, who lives in Canada.

"And I couldn't die without seeing her. So then I decided to leave," he said.

Ali said he didn't hear anything from the American government, even after he registered as a citizen trying to leave. But it was his American passport that eventually got him out — through the Rafah crossing into Egypt this past Friday.

He said those who crossed were put on a bus and they traveled for hours through checkpoints and searches until they eventually arrived at a hotel in Cairo Saturday morning.

"The only thing I wanted to do is just go have a shower," he said. "For 26 days, you don't even wash your face or brush your teeth, and [you are] in the same clothes. And it's hot during the day, and you're sweating."

Ali spoke to All Things Considered host Mary Louise Kelly on Sunday from Cairo, where he said he was preparing to move on to Malta.

Qassam Ali: I have to leave tomorrow morning, because they give us 72 hours. I don't understand why. I have a house in Cairo, I have a farm in Cairo. [The U.S. officials say] "You'll have to leave." So I decided to go to Malta and just spend some time there to see and then to think [about] what I'm going to do after I've recovered.

Mary Louise Kelly: So where is your mother now? Where is your sister?

Ali: My mother and my sister and my niece and nephew are still there in Gaza. They refuse to leave. They decide if we're going to die, let's die in our house. Of course, this is why I'm not happy leaving, because I'm worried about them. My mother, she raised us, seven kids, by herself — [we] got the best education. So I love my mom, and now I am leaving her.

People think I'm happy to leave. No. Usually, I travel a lot in my life out of Gaza, and always I feel Gaza is a prison. When you get in, you get in the prison. Always you need permission to leave and always I am happy to get out of Gaza ... But this time I don't feel I am free. I don't feel I am safe. Because part of me is still in Gaza.

Kelly: Do you think you'll ever go back? Do you think you'll see Gaza again in your life?

Ali: I don't know. I love Gaza. I am addicted to Gaza. You know, I have a chance to live comfortably all over the world, but I always come back to Gaza. I don't know. If my mother stays alive, I will go. Even if nothing is for me there after all of this destruction ... I don't like to die without seeing Gaza again.

Kelly: You said you feel angry now. At who? Who do you blame for what's happening to your home, to your family?

Ali: Israelis and the Americans. And really I'm angry at Mr. Biden.

Kelly: Even though the U.S. helped you get to safety? Even though the U.S. helped you get out?

Ali: Oh, no no no. No no no. Take me to safety? No no. Not at all. When they're helping in the destruction of your own people? I think the American government, even with this situation, they were cheap. When they put us in the hotel and they tell us, "You have to leave in 72 hours. If you want to go to the States, you have to organize the ticket."

This is the American government which is giving Israel $14 billion, and they are not capable of taking charters for their own citizens to the United States and told me I have to be thankful for the American government? Why? There is a duty to protect and to help their own citizens, no matter what their background is – they are Palestinians or Israelis or Europeans, or anywhere. All United States citizens are from immigrant origins. Why this discrimination?

As for what's next, Ali said he wants to see his daughter in Canada — and his other kids — but not right away. He said he needs time, psychologically and physically, and he wants to protect his kids from what he has experienced.

He doesn't want to bring the war to them. He just witnessed so many kids in Gaza who have no choice but to live through it.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.