Caption

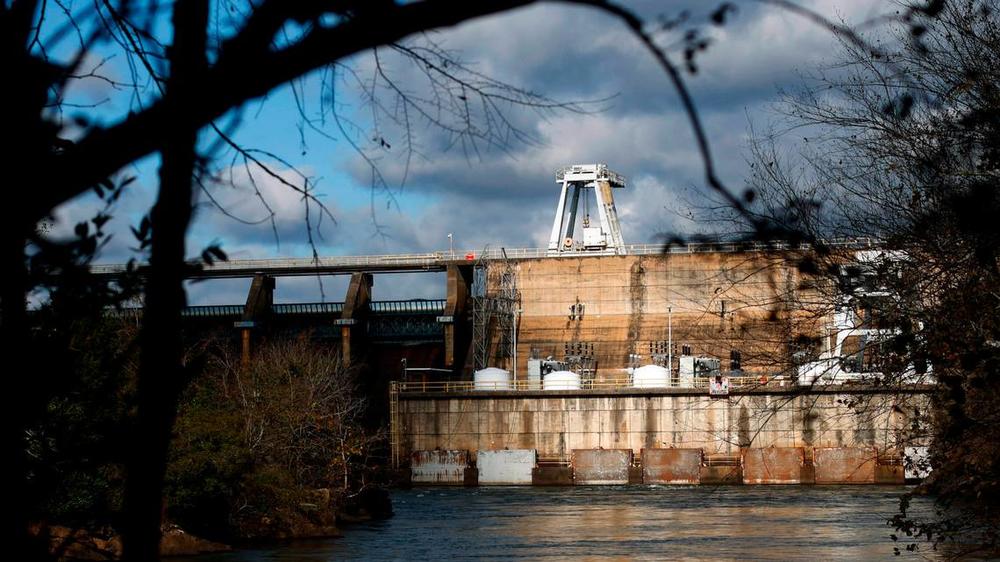

This is a portion of the Lake Oliver Dam in Columbus, Ga., where, in October 2020, industrial diver Alex Reed Paxton lost his life in a routine inspection for damage.

Credit: Mike Haskey/Ledger-Inquirer

This is a portion of the Lake Oliver Dam in Columbus, Ga., where, in October 2020, industrial diver Alex Reed Paxton lost his life in a routine inspection for damage.

Industrial diver Alex Reed Paxton plunged into the bowels of Columbus’ Lake Oliver Dam on Oct. 27, 2020, and never got out alive.

As he descended into the water along a floodgate chain looking for damage, his left arm was sucked into a high-pressure pipe, its valve inadvertently left open, and the suction’s crushing power suffocated him.

Pinned by 850 pounds of pressure, the 31-year-old lost consciousness, and died in minutes. His body did not come free until workers found the valve control and released it, about 30 minutes later.

Represented by Columbus native Jeb Butler of the Butler Kahn law firm in Atlanta, his parents sued Georgia Power, which operates the dam. The claim went to mediation, and they reached a confidential settlement last month.

Some aspects of Paxton’s death remain undisclosed, as diagrams and details of how the dam operates are not public record: Federal authorities consider it “critical infrastructure” that terrorists or foreign agents could target, were they privy to its inner workings.

Chance Corbett, Columbus’ homeland security director, agreed that the power company has to keep some information confidential.

“They don’t want to reveal any vulnerable points to it,” he said of the dam, adding authorities have to protect residents living within the river’s flood plain.

Still, Paxton’s case sheds light on what happened in the dark interior of the dam that powers four hydroelectric turbines and helps regulate the Chattahoochee River’s flow to Columbus’ downtown whitewater course.

Camera footage of Columbus’ Lake Oliver Dam on Oct. 27, 2020, where Industrial diver Alex Reed Paxton plunged into the bowels of the dam's workings looking for damage.

The 10-inch opening to the pipe that snagged Paxton’s arm pulled water from a vertical space within the dam, called the headworks, where Lake Oliver’s backwater flows through when the chain pulls open the dam’s metal headgate.

The pipe, called a priming pipe, feeds water to what’s called the penstock, another pipe about 20 feet in diameter, which at high velocity sends water to the turbines to generate electricity.

Opening the headgate to power those turbines first requires “priming” or “watering up” the penstock, Butler said. That requires opening valves to fill the penstock with lakewater.

Before a diver descends into the headworks where Alex Paxton was working, all valves controlling the flow to the penstock have to be closed, otherwise the differential pressure can trap the diver.

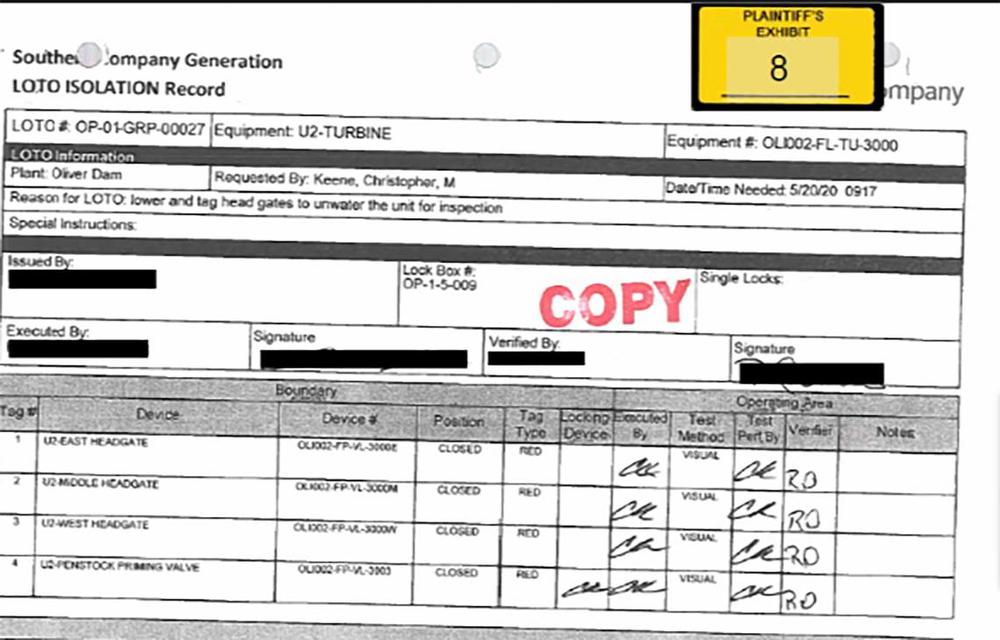

Georgia Power through its lockout-tagout safety checklist was supposed to have closed two valves where Paxton was inspecting the gate chain.

One penstock valve was a flapper, like the kind used in a bathroom toilet, and the other one was a gate valve controlled by a wheel, like on a water spigot.

First filed in Muscogee State Court in March 2022, before being moved to the federal level, the lawsuit accused Georgia Power not only of failing to close both valves, but of neglecting to note the gate valve even existed, on safety forms used at the time.

A "lockout-tagout" safety form used at Columbus’ Lake Oliver Dam in 2020.

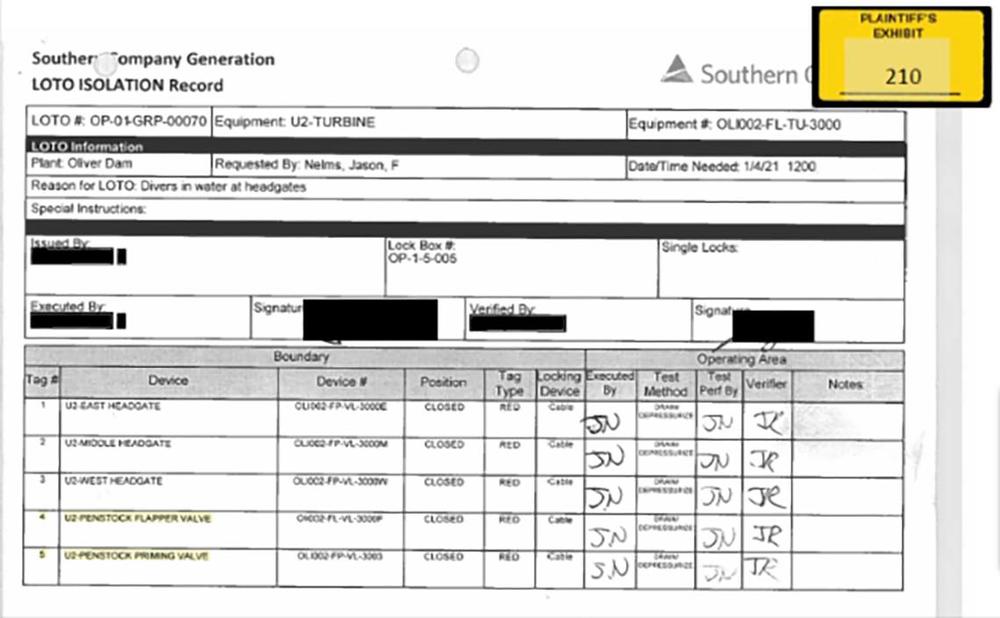

The utility showed the dive team from Glenn Industrial Group of Charlotte, N.C., a lockout-tagout list that didn’t have that valve on it.

The flapper valve was noted on the form, and it was closed during the tag-out safety protocol.

The wheel controlling the other valve was behind a locked gate only Georgia Power staff had access to, the lawsuit said. That’s what took so long to free Paxton.

Georgia Power since 2018 had contracted with Glenn Industrial for maintenance work on the dam.

In depositions taken for the lawsuit, witnesses said the company had a safety meeting with Glenn Industrial on May 27, 2020, when the gate valve was shown to the dive team.

Records showed Georgia Power broke the headgate gate chain to its Unit 2 turbine on Oct. 21, 2020, a week before Paxton’s death.

With no mention on the tag out form, the gate valve noted during the May safety meeting still was overlooked five months later, when Paxton made his dive.

Georgia Power later corrected that oversight.

A "lockout-tagout" safety form used at Columbus’ Lake Oliver Dam in 2021.

Paxton wore a wet suit and a helmet with a light and camera on it. He had radio contact with a colleague monitoring him from atop the dam.

The time stamp on footage from his dive camera shows a descent at 12:42 p.m., the chain to the floodgate in his view.

In 12 seconds, he screams.

“Alex?” asks his colleague.

“I’m stuck!” he yells.

“What?” the coworker asks.

“I’m stuck!” Paxton repeats.

“Get him up!” his contact orders.

Sucked in up to his shoulder, he could not be pulled free.

He was an experienced diver, with 10 years’ experience. Unmarried, he left no children. He lived in Mount Pleasant, N.C., outside Charlotte.

The coworker who monitored Paxton’s dive told attorneys they were only checking the headgate chain for damage, and assumed it would be a simple task.

“This was supposed to be an easy dive: Go see what’s wrong with the chain,” he said in his deposition.

He volunteered to go himself, he said: “I said, ‘I’ll do it if you don’t want to.’ Didn’t think anything of it.”

The routine task was not worth losing a life, he said. “No job is worth that.”

Paxton’s parents, Kenneth Paxton of Ohio and Kathryn Hartley of North Carolina, did not want to comment on the case, Butler said.

He credited colleague Paul Giannotti with handling crucial aspects of the claim, and noted the law firm has created a web page to document the accident.

The attorney representing Georgia Power was Josh Archer of the Atlanta firm Balch & Bingham. He did not respond to a Ledger-Enquirer email seeking comment.

The utility has sued Glenn Industrial, claiming the contractor signed an agreement waiving any liability claims related to its work on the dam, and was solely responsible for its workers’ safety.

Georgia Power “is entitled to reimbursement from Glenn Industrial for any and all attorneys’ fees and expenses of litigation,” says that suit, filed in April 2022.

Because that lawsuit continues, Glenn Industrial’s attorney, T. Langston Bass of Brennan, Harris & Rominger of Savannah, declined to speak about Paxton’s death.

“This case is still in litigation, so I will not be able to comment,” he wrote in an email.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Ledger-Enquirer.