Section Branding

Header Content

Weather experts in Midwest say climate change reporting brings burnout and threats

Primary Content

Chris Gloninger was excited to start his new job as chief meteorologist at KCCI, a TV station in Des Moines, when he moved to Iowa from Boston in 2021. Gloninger had extensive experience — more than 15 years in TV meteorology, which included a regional Emmy-award winning weekly series on climate change.

He looked forward to connecting the dots between weather and climate change trends, but suspected it may elicit some grumbling from Iowan viewers.

"I expected pushback," he said. "I just didn't expect the magnitude and how quickly it went off the rails."

At first the negative feedback was fairly standard.

"It was stuff like, 'I don't need to hear your liberal conspiracy theories on our air. Take the politics out of your forecast,'" Gloninger recalled. "'You're politicizing the weather, you're a puppet to the left.'"

But one year in, Gloninger began receiving a steady flow of harassing emails.

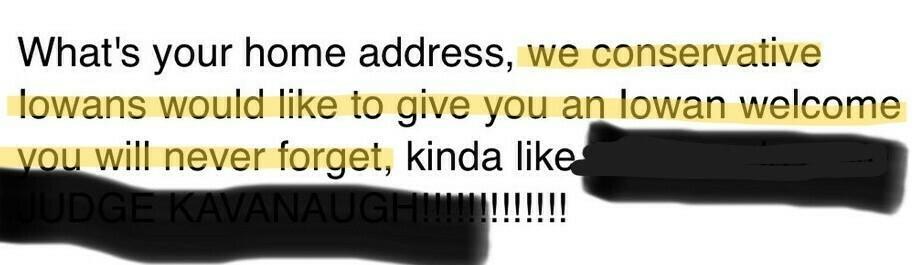

In one, the sender asked for his address and said, "We conservative Iowans would like to give you an Iowan welcome you will never forget."

That message also referenced an incident where police arrested a man carrying a gun, a knife, and zip ties near U.S. Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh's house.

Gloninger's bosses arranged for security to tail him when he came to and from work and when he worked in public, including the state fair. But he said the threats ate away at his mental health and well-being.

"You never know what hill someone's willing to die on," Gloninger said. "I didn't know if this person thought risking his future to shut me up was worth it — and that plays in your mind."

Eventually, Iowa resident Danny Hancock pled guilty to a third-degree harassment charge and was fined $150.

But the threats – on top of family health issues and shifting priorities from KCCI's management – eventually became too much for Gloninger.

"You can kick somebody when they're down only so many times before they just have to give up," he said. "And I felt like it had just gone too far."

After two years in Iowa, Gloninger moved back to Massachusetts to be closer to his family and take a consulting job focused on climate solutions.

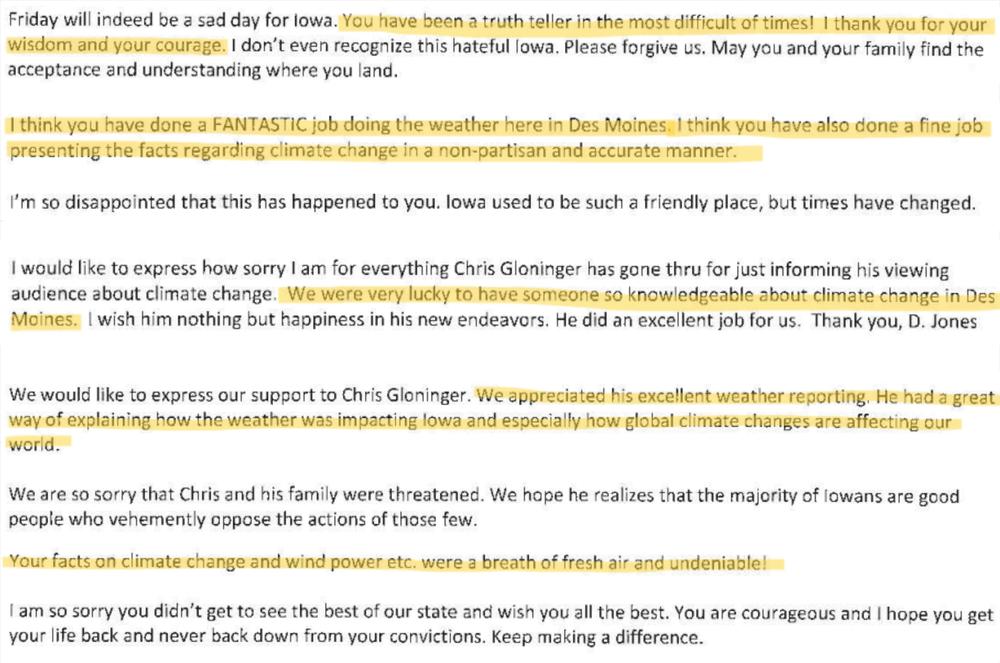

Before he left, he went on air and talked about the harassment he faced. In response, he received hundreds of messages from grateful viewers.

"I would like to express how sorry I am for everything Chris Gloninger has gone through for just informing his viewing audience about climate change," wrote one viewer. "We were very lucky to have someone so knowledgeable about climate change in Des Moines."

Gloninger's experience echoes the treatment of other public-facing officials in recent years, including election workers, educators, and public health officials.

'I didn't have anything left to give'

Hostility from the minority can be a challenge for people on the front lines of climate communication. Climatologists and meteorologists in seven states shared stories with Harvest Public Media of encountering strong resistance.

In Nebraska, it became too exhausting for Martha Durr, who stepped away from the state climatologist position earlier this month. She said she didn't feel she had "anything left to give" the job.

"I went to school to become a scientist," Durr said. "And what I found myself doing most of the time in this role is almost being a therapist and helping people through climate change."

Durr said she tried to be empathetic and meet people where they were, pointing out local impacts of climate change.

"Sometimes you run into a wall, or things could even feel combative," Durr said, describing an instance where an audience member shouted at her that her information wasn't helpful.

"I'm really tired of that," she recalled feeling afterwards. "Everyone should have their own opinion but I don't need to be called out on stage, after I drove six hours to give a community presentation."

After nearly eight years in the role at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, she said she didn't have the energy to keep repeating the same message without seeing progress.

"It gets tiring trying to convince people that science is real," Durr said. "If you want to do that, you can go talk to somebody else. But I'm not at a place where I want to keep doing this. I would rather be helping people work through solutions to solve the problem."

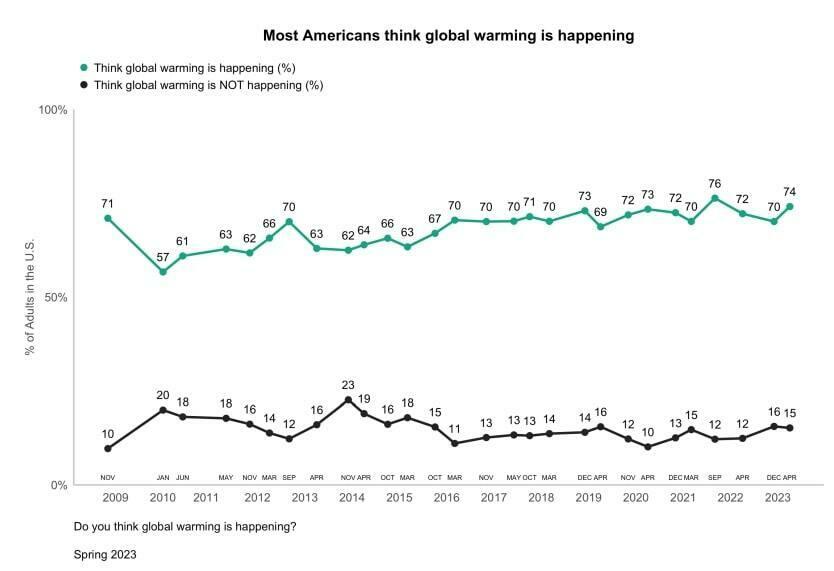

Surveys suggest most of the public appreciates climate change reporting

While resistant voices can be loud, 90% of Americans are still open to learning about climate change, according to Ed Maibach with the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University.

Maibach said surveys suggest people appreciate hearing about climate change from trusted sources like meteorologists and climatologists, even in conservative communities.

"The whole notion of 'red and blue states' actually creates a disservice when it comes to thinking about how to educate the public about climate change," Maibach said. "It signals that this is difficult, if not impossible, to do in red states. But that's just not true."

Jim Gandy's experience bears that out. In 2010, he became the first TV meteorologist to participate in Climate Matters, a climate change reporting program. The program adviser asked him to explain local climate change impacts to viewers in Columbia, South Carolina.

"I said, 'I'd love to be the test case,'" said Gandy, who is now retired. "Because I don't live in a red state, I live in a dark red state. And if you can talk about climate change here, you can talk about it anywhere."

Gandy's audience embraced his reporting, and Climate Matters now provides climate science resources to meteorologists and journalists in 95% of U.S. media markets.

Navigating pushback

Melissa Widhalm, who spent years presenting the science to communities in Indiana, said she's used to encountering wary audiences.

She said most people are willing to have a conversation about climate change and are eager to learn from a credible scientist. Even so, she said she had some strange encounters during trips to Indiana communities.

"Every time you went out, you just weren't sure what you were going to get," said Widhalm, who is now the associate director at the Midwestern Regional Climate Center. "You always went in having to mentally prepare yourself that somebody could be there to cause trouble."

Meteorologists and climatologists in the Midwest and Great Plains who spoke with Harvest Public Media said they try to focus on local impacts of climate change that people can see in their own backyards.

Widhalm said she didn't shy away from what that means for people's lives.

"I really tried to humanize what we were talking about," she said, noting that higher temperatures mean a longer growing season, which causes a longer allergy season. "If you or somebody in your household has allergies, you understand what that means to suffer for more weeks out of every year."

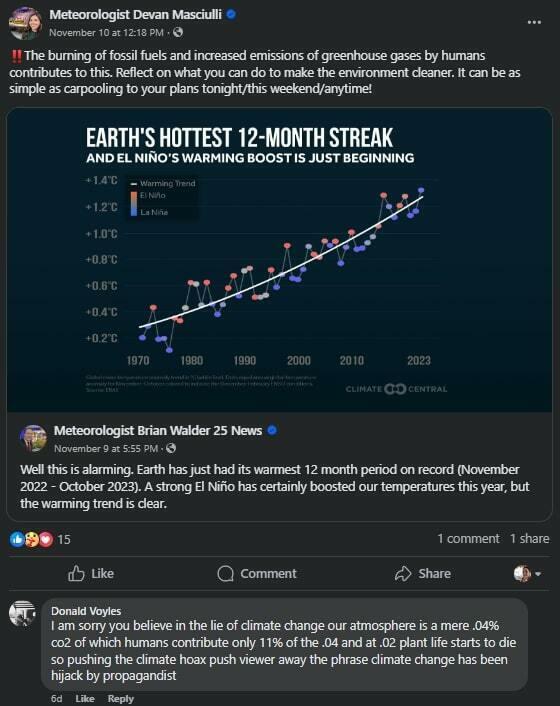

Comments on social media posts are where Devan Masciulli – a meteorologist at WEEK 25 News in Peoria, Illinois – sees the most pushback.

She said she tries to keep the focus on the science.

"But you're still met with people saying you're lying or that you have ulterior motives," Masciulli said. "I could see it wearing on you to where you think, 'I'm not even going to post it because it feels like nobody's listening.'"

Illinois climatologist Trent Ford adjusts his framing when he speaks to different groups. He said it's more than just switching out words – it's about dialing in on the most relevant information and explaining workable climate solutions.

"The message is the same if I'm talking to an environmental nonprofit or a farm bureau in a conservative county," he said. "But the way the message is delivered may differ."

Even in a blue state, Ford received a threat earlier this year after he talked about climate change while explaining some gloomy Chicago weather on a radio show.

Ford's employer, the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, determined there wasn't an immediate threat.

"Somebody just decided to blow off some steam in a pretty unproductive fashion," Ford said. "Everything was handled very professionally. It was a little surprising, but I never felt unsupported or unsafe."

Staying motivated

Widhalm, of the Midwestern Regional Climate Center, said she's not easily disappointed – she knows explaining climate change in Indiana can be a challenge.

"I never went in expecting that I would move the hearts and minds of the masses," she said. "Even just a small connection and conversation feels like we've way overshot what we're trying to do."

On days when her job feels like an uphill battle, she said she wonders if it might be easier elsewhere. But she said the challenge itself is a reminder of why she should keep going.

"There's nowhere else that is more important to do this work than right here in Indiana," Widhalm said. "Because otherwise it would not be talked about at all and that's very centering. It keeps me going when I'm thinking, 'What's the point?'"

This story was produced in partnership with Harvest Public Media, a collaboration of public media newsrooms in the Midwest. It reports on food systems, agriculture and rural issues.

Copyright 2023 Harvest Public Media. To see more, visit Harvest Public Media.