Section Branding

Header Content

Georgia Today: New Fulton County Jail feasability study; Peach Drop canceled; Book author interview

Primary Content

On the Friday Dec. 8 edition of Georgia Today: Fulton County's new jail could cost Georgia taxpayers $2 billion; bad news for fans of Atlanta's annual Peach Drop ceremony; and a journalist who writes about race finds his most important story through a discovery about his own family.

Orlando Montoya: Hello and welcome to the Georgia Today podcast from GPB News. Today is Friday, Dec. 8. I'm Orlando Montoya. On today's episode, Fulton County's new jail could cost Georgia taxpayers $2 billion. Bad news for fans of Atlanta's annual Peach Drop ceremony. And a journalist who writes about race finds his most important story through a discovery about his own family. These stories and more are coming up on this edition of Georgia Today.

Story 1:

Orlando Montoya: A new jail for Atlanta's Fulton County could cost up to $2 billion to build and more than $200 million a year to operate. That's according to a feasibility study presented to county commissioners this week. The study estimated costs for a new detention facility to be located next to the existing troubled jail in a neighborhood west of downtown. The Fulton County Jail has been plagued by overcrowding, unsanitary conditions and violence. It's also the subject of multiple state and federal investigations. Commissioners discussed possible funding sources, likely a local option sales tax or a millage rate increase, and timelines, possibly 2029.

Story 2:

Orlando Montoya: A Georgia New Year's Eve tradition won't be returning this year. Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens said today the city won't host the Peach Drop, Georgia's 34-year-old twist on New York City's ball drop in Times Square. The event has been on and off for various reasons since 2017, but did ring in 2023. In a statement, Dickens cited the expense of city celebrations for the 50th Anniversary of Hip Hop this summer.

Story 3:

Orlando Montoya: At least five Georgians have been sickened in a salmonella outbreak linked to recalled cantaloupe. Health officials in the U.S. and Canada say at least eight people have died in both countries since the outbreak was first reported in mid-November. The Georgia Department of Public Health says the cases here involve people who range in age from 1 to 81. The recalled cantaloupe is sold in Georgia at Sprouts, Trader Joe's and Kroger stores. The agency advises caution with precut cantaloupe.

Story 4:

Orlando Montoya: Authorities have arrested a woman accused of trying to burn down the Atlanta birth home of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. A statement from the Atlanta Police Department identified the alleged attempted arsonist as 26-year-old Lanita Henderson. Police say she poured gasoline on the property before people at the site stopped her. The incident happened yesterday evening at the two story home in the Auburn Avenue historic District. The home is now a museum operated by the National Park Service.

Story 5:

Orlando Montoya: The Technical College System of Georgia has announced a new college and career-ready academy in Northwest Georgia's Walker County. The partnership between Walker County Schools and Georgia Northwestern Technical College creates the 58th such academy in Georgia. College and career-ready academies aim to create job pathways for high school students with an emphasis on local business partnerships.

Story 6:

Orlando Montoya: The White House today announced billions of dollars in spending for passenger rail across the country. GPB's Grant Blankenship reports, that includes the possibility of a high-speed rail link between Atlanta and Charlotte.

Grant Blankenship: $8.2 billion will go to the 10 first high-speed rail lines in the nation, like the 500-mile line between Los Angeles and San Francisco already under construction. Then there are other corridors which, though not shovel-ready today, are on track for future releases of cash. That's where you'll find the proposal for a high-speed line from Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport in Atlanta, passing through Athens and Augusta before ending in Charlotte, N.C. According to a senior Biden administration official, it's already cleared a key environmental assessment. In separate but related news, $1.5 million in federal infrastructure law grants will pay for studies into the viability of conventional passenger rail between Chattanooga and Savannah, with stops in Atlanta and Macon. For GPB News, I'm Grant Blankenship in Macon.

Story 7:

Orlando Montoya: Black communities in Georgia have disproportionately high fatality rates from certain diseases, but less than 5% of participants in clinical trials for treating chronic diseases and cancers are Black. A new initiative is seeking to change that. GPB's Ellen Eldridge has more.

Ellen Eldridge: Low clinical trial participation among the Black community is fueled by things like mistrust of the medical system, economic inequalities and a lack of awareness about the trials themselves. Maimah Karmo is the founder and CEO of Tiger Lily, a nonprofit focused on supporting Black women with breast cancer. She says more representation in clinical trials is necessary to find better and more effective treatments.

Maimah Karmo: People are dying, disproportionately, who are of color, so we have a choice to make. We can either just sit back and let the past define our future, or we get involved in policy change to protect people who are going to trials.

Ellen Eldridge: In Georgia, Black patients with breast cancer are 45% more likely to die of the disease than white patients. For GPB News, I'm Ellen Eldridge.

Story 8:

Orlando Montoya: Southeast Georgia has landed another auto parts supplier to serve the $7 billion Hyundai electric vehicle plant being built in Bryant County. The Effingham County Industrial Authority says Kyungshin America will locate to a site within 15 miles of both the Hyundai plant and the port of Savannah. South Korea based Kyungshin makes wire harnesses for automobiles.

Story 9:

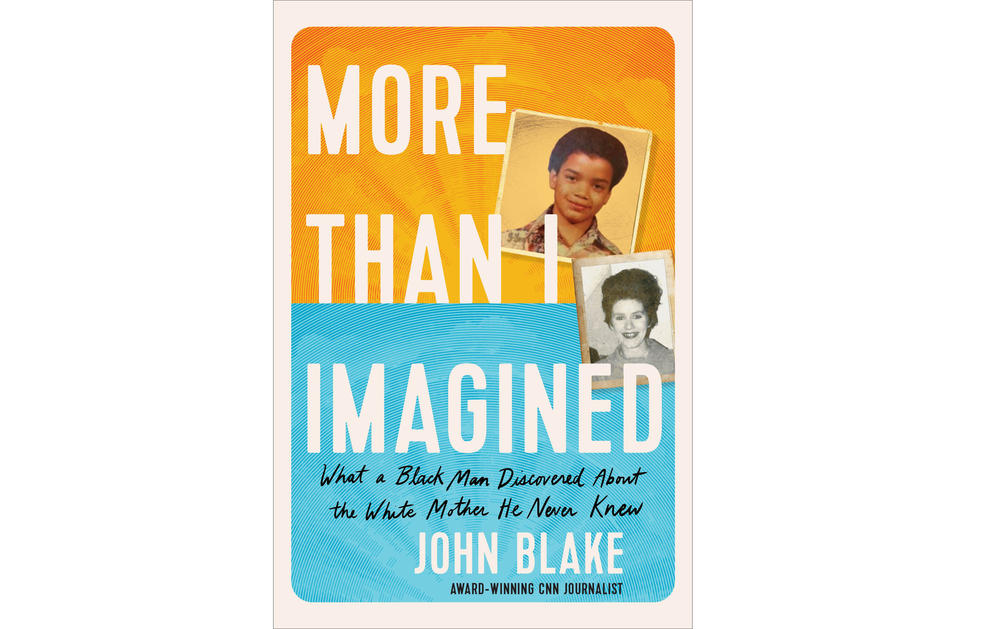

Orlando Montoya: Atlanta-based journalist John Blake has covered some of the biggest stories about race in America over the past three decades. But it's the CNN senior writer's own story about race that has become his deepest exploration into the issue. Blake joins me now to talk about his book published this year More Than I Imagined: What a Black Man Discovered About the White Mother He Never Knew. Welcome to GPB.

John Blake: Thank you for having me.

Orlando Montoya: Now, you write about how your feelings toward your mother and her family have changed over time. Why did you initially hide your biracial background?

John Blake: In the world that I grew up, having a white mother was a source of shame. And the community that I grew up in is pretty famous. It's West Baltimore, Md. It's the home of the HBO series The Wire — was filmed right in my neighborhood. It's also the epicenter for the 2015 violent protests that erupted when Freddie Gray, a Black man, died in police custody. And yet I grew up there with this secret. I grew up there is what I call a closeted biracial person. I had this white mother and this white family. But the catch was also that I knew nothing about them. My mother disappeared from my life not long after I was born, and her family didn't want anything to do with me because I'm Black. And so I grew up knowing that there was this white side of my family wanted nothing to do with me because of their racism and in this world where everybody hated white people, so I didn't want anybody to know I had a white mom.

Orlando Montoya: Then you found out that your mother also had schizophrenia and was institutionalized before you got to know her. Which was the more painful discovery for you?

John Blake: The most painful discovery was finding out about her mental illness because of the way it happened. I was 17 on my way to Howard University. I had heard nothing from her or my other side of my mom's family, so I thought my mom was perhaps dead or they didn't want anything to do with me because of, as I mentioned, racism. And then one day my father calls me to the bedroom and he just says, "Hey, do you want to meet your mom?" Three days later, I'm driven out to this menacing-looking red brick building in the Maryland — in the outskirts of Maryland. And it looks like a building from the movie Shawshank Redemption. I walk in there in the waiting room with my younger brother, Patrick, and we're told we're going to meet our mommy. We still don't quite know where we are. And she comes out and she sees us. And I hug her. It is awkward for me because I don't know what to say. I'd never even use the word "mom" before. But it's also awkward because of where we're standing. It's the waiting room of a mental institution, and nobody in my family told me that she was mentally ill. We didn't make that discovery until we were in that waiting room and hugging her. So that was, was what — that's one of the reasons it was so painful. It was a shock. Nobody prepared us.

Orlando Montoya: I think a lot of families have people or circumstances that no one talks about. If someone is listening right now and wants to know those truths, based on your experience, what's the best way to start?

John Blake: To reveal painful truths to someone in a family?

Orlando Montoya: If you have something that you — that no one talks about in your family, do you just—?

John Blake: Yeah.

Orlando Montoya: — say, "Hey, Mom, can you tell me about my dad?" I mean, it just — there were moments in the book where you just seemed to blurt out, "I want to know."

John Blake: Yeah, that's a good question. I would say, I guess two things about how to reveal painful family truths, because my story is full of many painful truths, and some of them were so extraordinary that it's hard to believe. But I think one is to understand that those painful truths will come out sooner or later. So you — it's best to get ahead of them. Because I think what people often try to do is they try to hide them and hope they never come out. But they do. And so, too, and when they do come out, whichever way they come out, I would say to hopefully make make sure that people are ready psychologically mature-wise to hear it. I don't know if I could have understood some of the things about my mom and her family if they had told me, say, when I was 7 or 8. I think they had to wait until I was older. I mean, I'm still trying to understand some of this stuff that happened in my mom's family, and I'm definitely older now.

Orlando Montoya: It's been a process, and it sounds like you've reconciled with pretty much everyone.

John Blake: Yeah, but that's — that — "reconcile?" That's one of the most dangerous words you can use when you tell the story about race. You know why? Because I think people find it — I know this sounds strange, but I think they find it kind of dull. When a Black person tells a story about reconciling with the white person, It's often seen as one of these Disney kind of "Blind Side" stories. Or the burden of forgiveness is placed on — placed on Black people. And, you know, we all live happily ever after. This wasn't that type of story. It was — what I learned about reconciliation, It was extremely difficult. You know, I had to convince members of my white family who wanted nothing to do with me because of my race, who freely used the N-word, that they had problems with race. And that was really difficult to do and that took a long time. So they had to change in ways they didn't expect. But in the process, they changed me in ways I didn't expect myself.

Orlando Montoya: I'm wondering, as a fellow journalist, if you think that our background as journalists helps or hurts fact-finding within family dynamics?

John Blake: That's another good question.

Orlando Montoya: Did you, for instance, bring your notebook to these conversations?

John Blake: I never thought of that. I did. What someone told me before I did this is that you have to treat your family like a source. You have to interview them. You think you might think you know your story, but you don't. And you might think you know your father or your mother's story, but you don't. And that was so true. As a journalist, I had to — that kind of training, you know, interviewing people, asking them tough questions, talking to them again and again, that was invaluable in telling the story.

Orlando Montoya: If you ask those questions, sometimes you're going to find answers that are going to be difficult.

John Blake: Right.

Orlando Montoya: And me as a journalist, if I'm talking about someone else.

John Blake: Yeah.

Orlando Montoya: You know, I can put it away intellectually in my mind.

John Blake: Yeah.

Orlando Montoya: But if I'm, you know, for instance, talking about my brother, the one who died when I was young and nobody talks about anymore, I have no idea how I'd react if I'd find out something about that.

John Blake: I think — that is true, but I think in some ways those are the best stories to tell where you don't know where it's going. I didn't know where the story was going that I was telling, even though it was mine. For example, you talking about how you don't know how you're going to react. There's kind of a villain in my — in my book. There's several and

Orlando Montoya: Your aunt?

John Blake: Yeah, you got it. Like, so, you know, here's my aunt, my mother's sister, who wanted nothing to do with us because we were Black. And then when I'm a young man, she suddenly decides she wants to meet me. And when I meet her, she won't admit that her racism had anything to do with her absence from my life. But then things happened to us where she became like a heroine in a story. Somebody is this great example. She changed in ways that I never expected. She taught me lessons about empathy and forgiveness that I never expected. So that was really surprising, that all these people that I met in my mother's family, that I — I saw them as villains, but I wasn't prepared for my reaction that they would become people that I would love and that I would admire in some ways, which is really something I didn't expect.

Orlando Montoya: Well, in the end, it is a hopeful book. I thank you for coming here and talking with me about it.

John Blake: Thank you for inviting me.

Orlando Montoya: I've been speaking with John Blake, a senior writer at CNN. His book is called More Than I Imagined: What a Black Man Discovered About the White Mother He Never Knew.

And that's it for today's edition of Georgia Today. If you'd like to learn more about what our news team is up to, visit gpb.org/news. You'll find the latest stories there. If you haven't yet hit subscribe on this podcast, do that right now. That way you stay up to date with us in your podcast feed. If you have feedback, we'd love to hear that. Email us at GeorgiaToday@GPB.org. I'm Orlando Montoya, sitting in for Peter Biello today. It's been a pleasure to be with you. Have a good weekend.

---

For more on these stories and more, go to GPB.org/news