Section Branding

Header Content

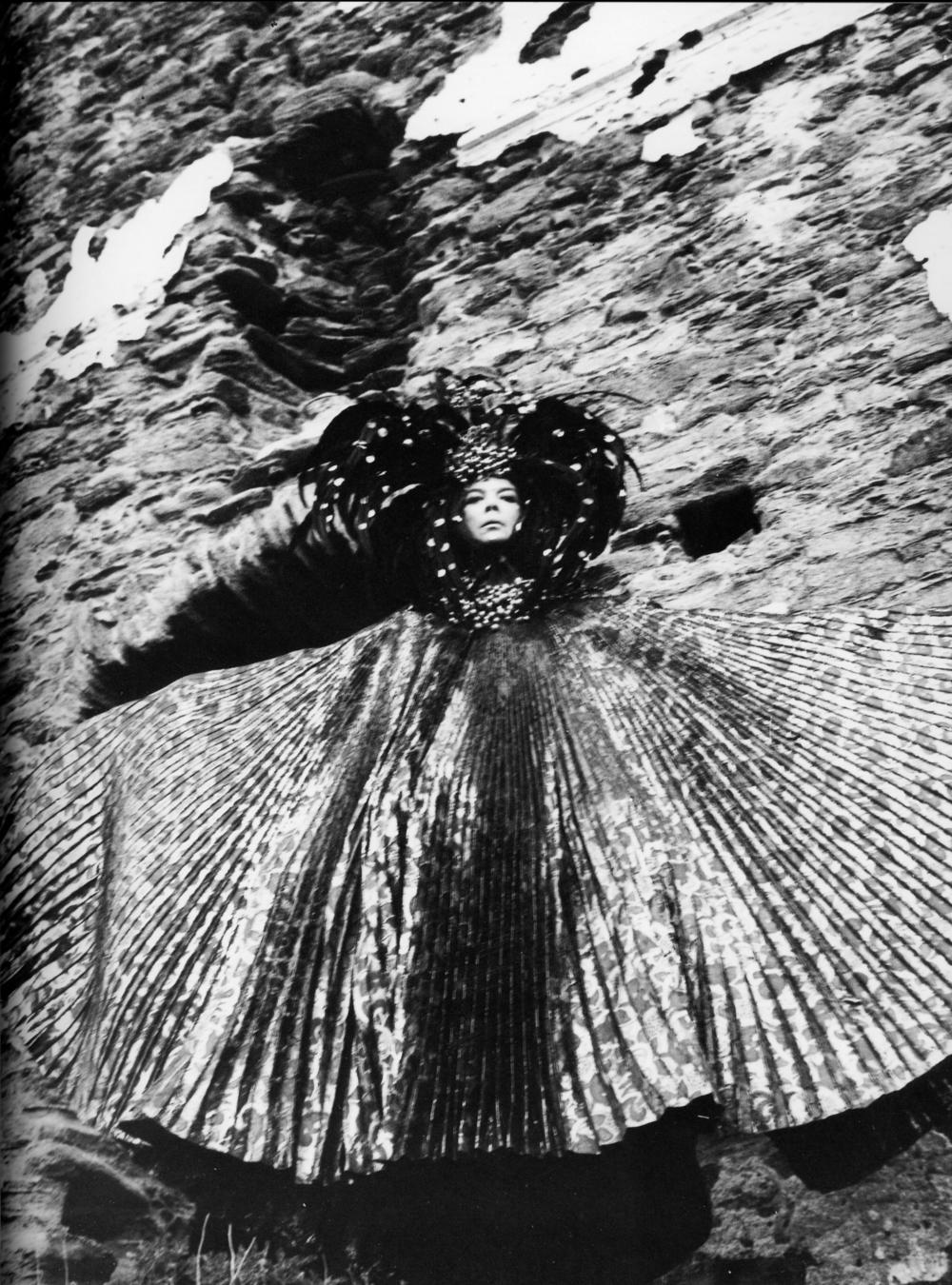

'She was a pure creator.' The art world rediscovers Surrealist painter Leonor Fini

Primary Content

An overlooked female artist is starting to get her due.

Nearly 30 years after her death, Leonor Fini's captivating, often gender-bending images are attracting renewed attention. She is one of the featured artists at the annual Art Basel fair underway this week in Miami, where many in the art world are gathered. There, San Francisco's Weinstein Gallery has joined with Paris' Galerie Minsky to mount a show of some of her most important work.

Fini, who was born in Argentina before moving as a child to Italy, outlived most of her contemporaries, Surrealist artists like Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí and Rene Magritte. She died in 1996 at 89 years old.

She is now considered part of that movement, but gallery owner Rowland Weinstein says she wasn't just a Surrealist painter. "She was a pure creator. She continually changed... In that essence, I think she was kind of like Picasso. She loved theater, design, costume design. And she was kind of a genius in all of them."

Although she had no formal training, Fini became an accomplished artist by sketching cadavers at the local morgue. She began her career in Italy and then moved to Paris where she became intimate, artistically and sometimes romantically, with Surrealist artists including Ernst, Dalí, Leonora Carrington and Man Ray.

She was also part of the first major Surrealist exhibitions, but Weinstein says the founder of the movement, French writer Andre Breton, didn't accept her as one of them. "If [Breton] said you were a Surrealist, you were," Weinstein says. "If he didn't say you were a Surrealist, you could paint surrealistically, but you weren't a Surrealist. And he would not have a woman be a Surrealist. In his view, women were muses."

Fini was a flamboyant, eccentric and glamorous participant in the Paris art scene, often appearing at events in costume or dressed like a man. As an artist, she was productive over a remarkable six decades. In the 1950s and 1960s, she became immersed in stage and costume design for theater and opera companies, even contributing costumes for Federico Fellini's film 8½.

Paris gallery owner Arlette Souhami, now 82, first met Leonor Fini in 1978. She found the artist overwhelming, opinionated and fascinating. "I worked all my life for Leonor," she says. Souhami continues her story in a mixture of English and French, interpreted by her friend Victor Picou: "When she met Arlette, Leonor said, 'I don't like women in general' and Arlette said, 'Neither do I.' And she said, 'OK we're going to get along, right,'" Picou laughs.

Souhami became Fini's art dealer and worked with her for the rest of the painter's life. It was an intense relationship. She says Fini called her five times a day.

For a show in the 1980s, Souhami recalls combing Paris bakeries to find 20 white cakes that surrounded the artist, dressed also in white, for a video and photo shoot.

Fini fascinated the other artists and photographers in her circle. "There was a time" Weinstein says, "when the most expensive photograph ever sold at auction was a piece by Henri Cartier-Bresson which was a woman floating naked in the water from the neck down. And it's stunningly beautiful. Nobody knew this at the time but it's Leonor Fini."

Fini's connections played an important role in gaining recognition and acceptance for the emerging Surrealist movement. When her childhood friend, art dealer Leo Castelli opened his first gallery in Paris, she curated his premier show, a Surrealist exhibition. She also created a number of pieces for the show, including an armoire with paintings of herself on its two doors.

Castelli, who moved to New York, became an immensely important art dealer, later also championing the emerging Abstract Expressionist movement. Weinstein says, "Castelli actually said that had he not known Leonor Fini, his life might have been very different."

In some ways, Souhami says Fini's personal life was as fantastic as her Surrealist art. For much of her life, she lived in a relationship with two men, who shared her Paris home. "She was free," Souhami says. "She was the most extraordinary artist... but she was also, neither man nor woman. She was androgynous."

Souhami says Fini's progressive, radical at the time, approach to gender identity stemmed from her childhood. Fini said her mother disguised her as a boy in her early years in an effort to evade attempts by her father to kidnap her in a custody dispute. "You can see that in her painting," Souhami says. "You can see men that look like women and women that look like men in her paintings. So, it's very fluid."

One of the paintings in the Fini exhibition in Miami shows the artist, fully-dressed, leading her semi-naked male lover. Weinstein says it's a role reversal from paintings that typically show a naked woman reclining before a fully-clad man. Weinstein says that was revolutionary. "She presents herself very strong, very powerful," he says. "Clearly the dominant person in the painting is Leonor Fini."

Interest in Fini has risen in recent years among collectors and museums. One of her paintings sold last year for $2.3 million.

As with other women artists like Frida Kahlo and Leonora Carrington, some of the fascination with Fini's personal life runs the risk of obscuring her achievements as an artist. According to art historian Tere Arcq, "Sometimes, Leonor Fini has sort of been put in a box of the eroticism in her paintings and how free she was in terms of sexuality. But she was much more than that."

Weinstein quotes the artist. "Her art was Fini and her life was Fini." For her, he says, "it was one and the same."

There are two major Fini exhibitions now in the works. Arcq is curating one next year that will open in Milan and travel to other cities, the other opens in Frankfurt, Germany in 2026.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.