Section Branding

Header Content

More options, less stigma: How Georgians in recovery are breaking barriers to addiction care

Hero Image

Primary Content

For Jocelyn Wallace, a former paramedic from Douglas County, her opioid addiction started like many others — with a prescription to treat her pain after a car accident. She was 16 years old at the time.

Her addiction would endure far longer.

“For over 26 years, I was stuck in opioid use disorder,” Wallace said. “I got married and had kids and my disease just continued to grow.”

It has been six years since Wallace last used substances, but she still vividly remembers what it felt like to be waiting for placement in a treatment or detox center to get help.

“I'd be looking at my watch going, I mean, '15 minutes from now, I'm going to be violently ill; somebody's got to help me,'” Wallace said. “And then I would give up. And I would leave. Very rarely did I even call them the next day.”

Sometimes, wait times were too long, or her insurance wouldn’t cover it. More often, it was the personal shame she felt of her addiction that kept her away.

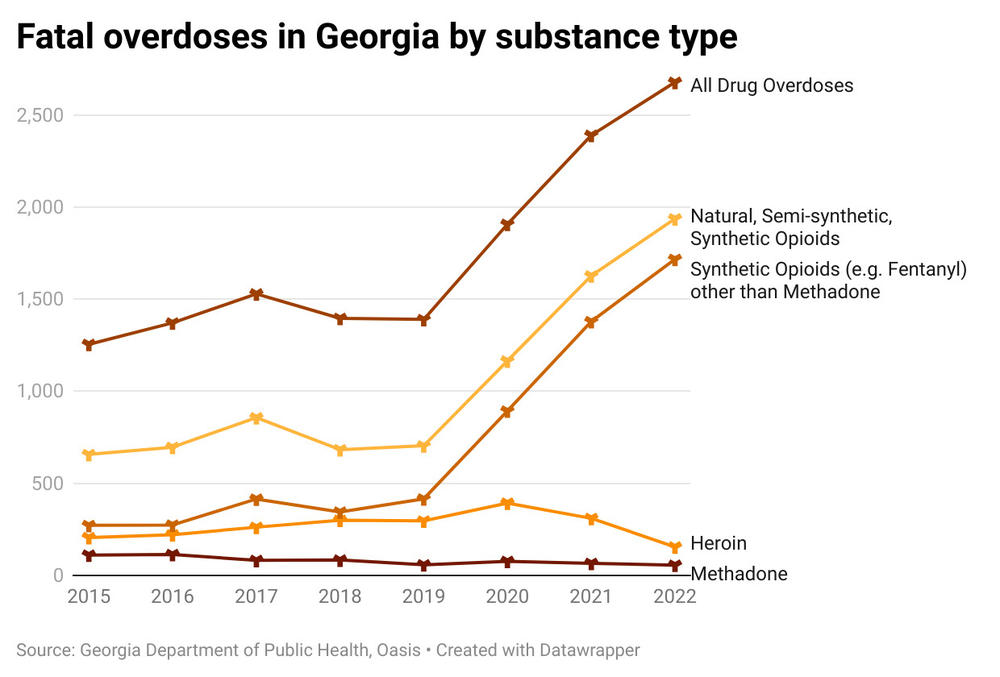

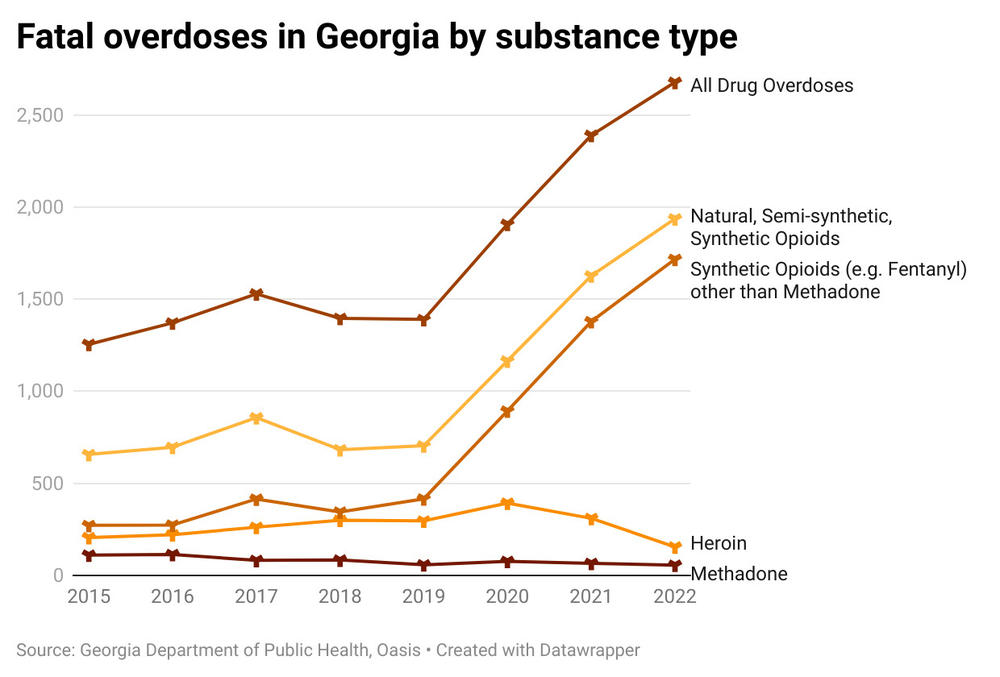

She's not alone. In 2021, 46 million people in the U.S. were diagnosed with a substance use disorder, or SUD. Last year, 2,600 people in Georgia died from drug overdoses, almost double from 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Opioid-related overdose deaths in particular have spiked in the past five years in the state, especially with the widespread introduction of fentanyl into the drug supply.

For people living with addiction, it’s been proven that access to evidence-based treatment and support can help keep them alive and stable. But care can be hard to come by and is only possible by combating the stigma around addiction, which is pervasive among providers, the public, and people with addiction themselves.

“Why isn't there access?” said Brian Kite with the nonprofit Georgia Council for Recovery. “Sometimes that is often because of stigma, or furthermore, discrimination.”

Discrimination based on a mental health condition that can very easily spin out of control.

Addiction is a disease

Substance use can start mildly at first, but over time, regular use of drugs and alcohol alters brain chemistry and causes compulsive use. Many people with a substance use disorder, or SUD, also have co-occurring mental health issues that can make the addiction harder to address.

SUDs can range from mild to severe.

Wallace said what she saw in her work as a paramedic stopped her from getting help. Wallace would revive people who had overdosed, often the same people every week, while she was navigating her own addiction.

“I didn't want to continue the life that I was living, but I was so terrified to be seen in that light," she said. "I was so terrified of what that would look like for me. Like we were hopeless, you know, we were a strain on the system.”

Though there’s no cure for addiction, there is treatment for SUDs. But 94% of those diagnosed with an SUD won’t get treatment on their own, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Of those who don’t get treatment, some aren’t ready to stop using. Others said they couldn’t afford it. Many people do not recognize they have a disease.

For others, like Michelle Jackson from Macon, getting help when she was going through a stimulant addiction just wasn’t something her family supported or understood.

“Somebody dies? Get high, get drunk," Jackson said. "No matter what happens in life, get high, get drunk. That was the answer. We don't embrace mental health help because otherwise you're crazy, you know?”

Jackson has a different perspective since starting recovery about 20 years ago, and after stints in rehab and detox facilities. Now she works with Macon’s River Edge Behavioral Health helping people who have been incarcerated and who also have a substance use disorder or other mental health issues.

“I come across people plenty of times in the five years that I've been doing this where their stories can almost line up to mine,” Jackson said.

Jackson said it was a “no brainer” to train as a forensic peer mentor. After years of feeling powerless against her own addiction — and uncertain about what kind of future would be available to her — Jackson’s now able to use her experiences to encourage others down a healthier path.

“I think about the people that were sitting around the table with me when I was doing crack cocaine," she said. "Several of them are not here now. Several of them have OD'd. If you don't have any hope, why are you going to try to be better?”

Evidence-based treatment

Because substance use can be chronic, it typically requires ongoing care and support, but many people with SUDs struggle to access services and have treatment covered adequately like other health conditions. This is especially true for people of color.

Plus, it’s not always guaranteed that addiction care will be covered by insurance.

Last year, The Department of Justice issued guidance protecting the right to treatment for opioid use disorder under the American Disabilities Act. Georgia passed its own law last year making it illegal for insurance companies to deny coverage for detox, treatment or rehabilitation services.

Though advocates say a parity law is a good first step in addressing stigma and holding healthcare providers accountable, there’s still a long way to go in the law being enforced.

“You can pass a piece of legislation, but if you don't have any teeth behind it, then to what extent does it actually happen?” said Dr. J. Aaron Johnson, a longtime substance use disorder researcher. “It just sort of remains to be seen the impact that actually has.”

Johnson, who's director of Augusta University’s Institute of Public and Preventative Health, has spent years researching access to evidence-based treatment for SUDs. This treatment ranges from daily medication to cognitive behavioral therapy, and fully depends on the severity of a substance use disorder.

Research shows evidence-based treatments can be life saving. But Johnson says he’s encountered “resistance” among rural health care providers in providing a key component of care: medication.

Take access to one of the most common medication-assisted treatments for opioid use disorder: buprenorphine, a main ingredient in Suboxone. It helps during withdrawals and over time, eases opioid cravings.

Though easily available with a prescription and considered a gold standard of care, only a quarter of substance use treatment facilities in Georgia have it available.

“It could potentially be widely available if you had physicians and nurse practitioners, PAs, etc., that were more widely accepting of offering it,” Johnson said.

Johnson said that's because many of these providers still hold stereotypes around addiction.

“They don't want to become known as the place where people go to get their buprenorphine — or their comment might be, ‘Well, we don't want those kinds of people in our practices’ — that type of thing,” Johnson said.

Another effective medication for opioid use disorder, methadone, is typically administered in special clinics, but is currently available at only 20% of substance use treatment facilities in Georgia.

“Most methadone maintenance clinics are only going to locate in high-density areas,” Johnson said.

Johnson said better training and the implementation of universal screening for substance use could help reduce misconceptions about the disease and curb stigma.

“Don't just skip over the screening because you assume that a 70-year-old female cannot misuse alcohol or drugs,” Johnson said.

Back in Douglas County, that’s just the kind of myth 68-year-old Cyndi Burnett believed.

“I didn't start really drinking heavy till I was in my 50s,” Burnett said. “I kept saying to my husband, 'I can't go to rehab; I'm a teacher.' And never once did I think I could walk in my principal's office and say, ‘I have a problem and I need some help.’”

Countering the narrative

Burnett did eventually get help through Alcoholics Anonymous. Now, she works with former paramedic Jocelyn Wallace at the Never Alone Clubhouse, one of 45 recovery community organizations in the state.

The number of recovery community organizations in Georgia like the Clubhouse has more than doubled from five years ago with help from the state Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities, which designated $4 million in 2018 toward amping up recovery services.

“Typically where you have seen funding for substance use or behavioral health in general was often geared towards prevention, and treatment and recovery was kind of an afterthought,” said Kite with the Georgia Council for Recovery.

Now, Kite argues, the state is undergoing a recovery “movement,” based on the idea that creating more spaces for connection gives people with substance use disorders a much higher chance at sustaining their recovery — as does connecting them to stabilizing resources, which many recovery organizations do.

Wallace opened the Never Alone Clubhouse a couple years back. It’s a place for people who are ready to address their addiction, and for her community to see recovery working.

“We're able to continue to educate the community that recovery is real and we're going to normalize recovery,” Wallace said. “It's expected. Let's get better.”

Because being able to ask for help in treating substance use should be the normal thing to do.

Georgia Public Broadcasting is part of the Mental Health Parity Collaborative, a group of newsrooms that are covering stories on mental health care access and inequities in the U.S. The partners on this project include The Carter Center, The Center for Public Integrity, and newsrooms in select states across the country.