Section Branding

Header Content

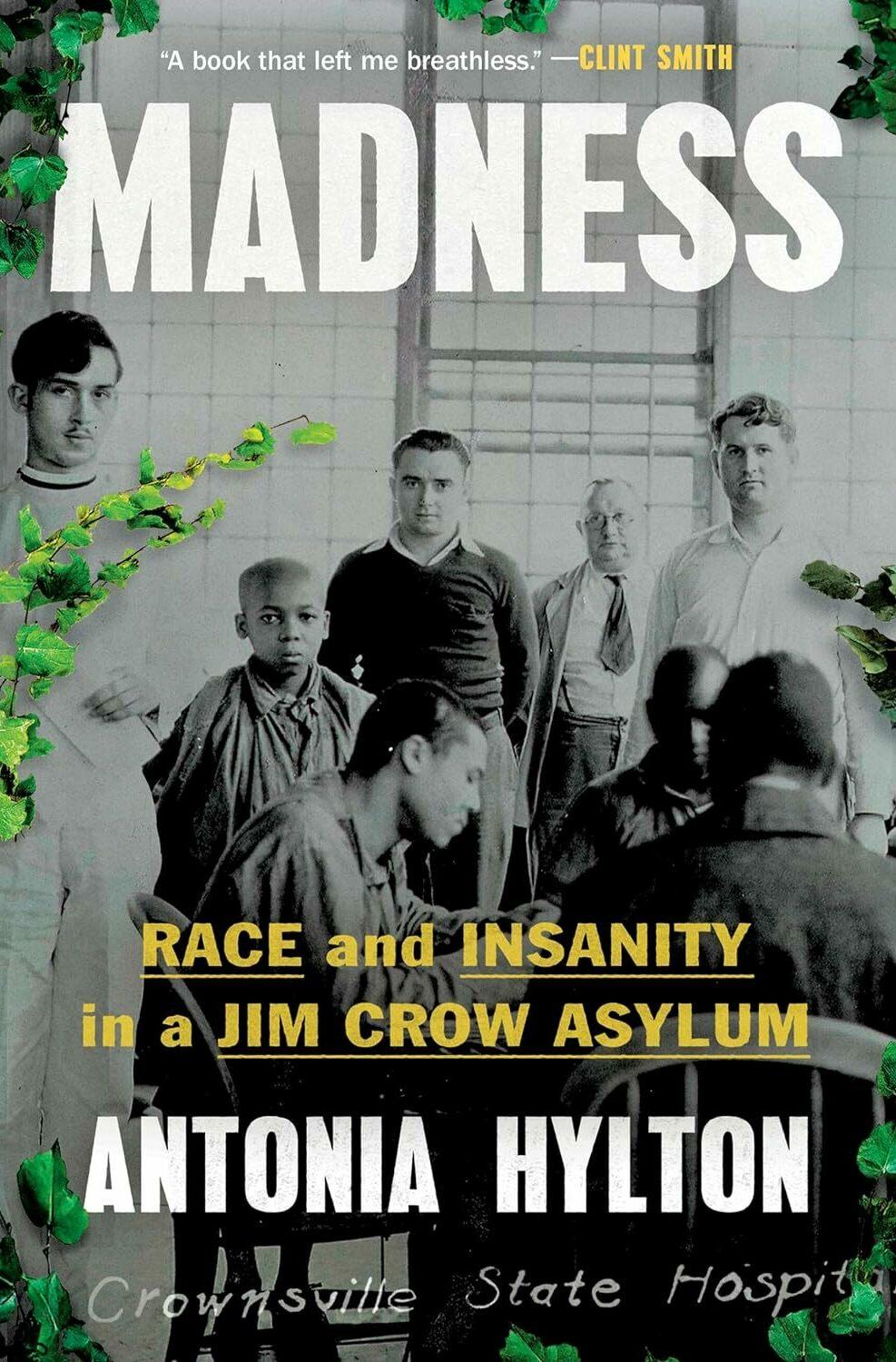

What a Jim Crow-era asylum can teach us about mental health today

Primary Content

From the outside, the Hospital for the Negro Insane of Maryland, which opened in Crownsville, Md., in 1911, looked like a farm, with patients harvesting tobacco, constructing gardens and working with cattle.

But Peabody award-winning NBC journalist Antonia Hylton says the hospital's interior told a different story. Inside, Crownsville Hospital, as it became known, had cold, concrete floors, small windows and seclusion cells in which patients were sometimes left for weeks at a time. And the facility was filthy, with a distinctive, unpleasant odor.

"There was a stench that emanated from most of the buildings so strong that generations of employees describe never being able to not smell that smell again, never being able to fully feel they washed it out of their clothes or their hair," Hylton says.

In her new book, Madness: Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum, Hylton pieces together the 93-year history of Crownsville Hospital, chronicling the lives of several patients and their families. The facility was built by its own patients — some of whom would go on to spend their lives there.

Hylton notes that from its opening until the late 1950s, the hospital operated as a segregated farm colony, with new Black patients being committed each week and the farm expanding, year after year. Patients at Crownsville ran everything from the laundry to the morgue, and were forced to cook meals and serve the white staff.

"This was about getting access to free Black labor," she says. "In the hospital records ... what you often see was a lot more commentary about the labor and the amount of products that patients could produce than you would see about mental health care outcomes, which, I think, tells you a lot about a facility's priority."

By mid 20th century, Crownsville Hospital had integrated its patient population. Hylton says the institution faded in prominence, as prisons and jails began housing more of the country's mentally ill. Though the facility closed in 2004, Hylton says the story of Crownsville connects directly to the current mental health care system — and specifically the stigma around mental health that exists within the Black community.

"I come from a very big Black family. ... We spend a lot of time together, but the one thing that we, for so many years, had a hard time talking about was mental health and mental well-being," Hylton says. "And it was because I had family members who had been sent to institutions like this one, who had suffered and then kind of retreated from our family's public life and day-to-day fabric."

Interview highlights

On how the legacy of slavery impacted the mental health care provided to Black patients

If you go back to the early 20th century to 1911, when Crownsville is first being created, you start to see the way in which the legacy of slavery and the ideas that white doctors and politicians and thinkers of the time, the way that their beliefs about Black people's bodies and minds completely shape the creation of this system, and it informs their decision to purposefully segregate Black and white patients, to create these separate facilities and then to treat them differently within those facilities. And so this was going on even before emancipation. Doctors would write very openly about their theories. Initially, the belief was that Black people were immune to mental illness because they so enjoyed being enslaved. They were protected by their masters, and they got lots of good time in the outdoors, while working on plantations.

That theory starts to shift once more and more Black people become free or they escape these plantations. And certainly after emancipation, doctors then start writing that they see a rise in mental illness in Black communities around the United States. And instead of spending a lot of time considering the ways in which slavery and the experience of being owned by another person and forced to work from day to night might cause trauma and poor health outcomes, they just assume that Black people can't handle being free.

On how patients were sometimes institutionalized at Crownsville for frivolous reasons

That parameter was incredibly wide and flexible. ... Most of it depended on the perspective of white police officers, of white neighbors and residents. I tell the story of a patient who was found in records by a Black staff member who comes to work at Crownsville in the 1960s, and she discovers that the patient's only reason for arriving at Crownsville is that they startled a white person driving in the road, they cut them off in traffic and startled their horse, and they are sent to Crownsville and labeled as insane. This idea that they would even dare get in the way of a white person is the entire impetus for their arrival at Crownsville, and they are, at the time that this employee discovers that record, in the institution for decades. ...

Authorities brought [another] patient into the hospital when he was walking around Baltimore and speaking in this funny accent. And they thought that he must have been making it up, essentially. They really had never met a Black person with an English accent. And so this man is brought to Crownsville, and it's not until a Black woman arrives and starts to see him as human, and worth talking to, ... that she discovers that he is from London and was a jockey and had moved to Baltimore and fell on hard times.

There were absolutely patients there struggling with real mental health diagnoses who had, in some cases, served in wars and come back and struggled with what we would recognize today as PTSD, but would have been called at the time something more like shellshock. And there were real mental health diagnoses, and there was real therapeutic opportunity actually, at this place. But all of that is complicated by and mixed in with the fact that the hospital really becomes a receptacle for any kind of Black person who ends up deemed as being unworthy, unwelcome or too unusual to meet the status quo and function in broader society in Maryland.

On including patient artwork and writing in her book

I wanted to do that to give them a voice, to give you a way to experience their perspective and their world, in a period in the hospital's history in which doctors really weren't paying so much attention to the patient's personal lives and experiences. And you can see they write about their loneliness. They write about fear. They write about their paranoia in this poetry. And so you really do get a sense of the patient experience. They write, at times, about the way in which they feel trapped there, or like people can be lost to this place.

On the shame and stigma surrounding mental health that still exists within the Black community

It's absolutely pervasive. ... While I was reporting on this, a family member of mine was in the midst of a psychiatric break. And they speak with me about these experiences in the book. And I shared them because I felt like I should disclose that as a journalist, I should tell you my connections to the story that I'm writing about. It shapes the decisions I make. So you should know what journey you're going on with me. ... My family had to go into crisis mode to try to support this person and find care for them in a system that is really hostile, at least, from my loved one's perspective, ... that is still very hostile to Black people.

On what we can learn from Crownsville and patients' stories

It's taught me a few lessons. The first is that I really deeply believe that if you try to swallow or stifle or hide your suffering, your pain, your worst memories, and you refuse to talk about them or seek help, ... that it never goes away. It never digests. You actually pass it on. And when I think about the research that some geneticists, epigeneticists are doing now that shows that trauma can actually be passed on, it can alter our DNA. ...

For me, most urgently, I think we need to have a new discussion, and vision around what community means and the role that that plays in mental health care.

Because, as you'll see in this book, at many points at which, [when] there is a recovery, there is a rescue, there is a patient whose story ends with positivity, it's not necessarily medication or a wonder drug or discovery that makes all the difference in their life. It is a community that wraps their arms around them. It is that they actually have support, and they actually are able to recover with the full knowledge that they'll be welcomed back somewhere, that they have a life ahead of them. And there are a whole lot of Americans and communities that do not feel that way, that they have something to fall back on. And the role that that plays in exacerbating, and contributing to, mental health crisis for adults. But also many clinicians believe really for children right now, it's at a crisis level. That's probably, for me, one of the primary takeaways.

Sam Briger and Susan Nyakundi produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Carmel Wroth adapted it for the web.

Copyright 2024 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.