Section Branding

Header Content

Why the 'world's coolest dictator' is on course for a landslide win in El Salvador

Primary Content

MEXICO CITY — El Salvador's President Nayib Bukele, the self-proclaimed "world's coolest dictator," is on course to win reelection by a landslide on Sunday, in a show of approval for his draconian security policies and rebuttal to critics who accuse him of widespread human rights violations.

The millennial president, who catapulted to the presidency in 2019 shortly after creating a new political party, has become a one-man juggernaut, a committed fan of bitcoin and one of the most popular leaders in all of Latin America, as he has relentlessly pursued powerful street gangs like MS-13 and overseen a massive reduction in homicides.

But this has come at a heavy cost: an indefinite, state of emergency has been in place nearly two years, undermining democratic safeguards, threatening freedom of the press and resulting in the arrest of more than 76,000 people. Critics accuse Bukele of flagrantly violating human rights and systematically dismantling the country's democracy—an idea he often seems to endorse.

"We were sold a fake security, a fake democracy, fake institutions, and a fake liberty. All the recipes they gave us failed. In over two centuries of our history, Salvadorans never knew peace," Bukele said in a speech he posted in January on X, formerly known as Twitter. Democratic principles, he seemed to suggest, are overrated.

The election is a reflection of Bukele's indifference to democratic norms: El Salvador's Constitution expressly prohibits presidents from running for a second term. But last year, a powerful court staffed by Bukele allies cleared the way for his re-election to another five-year term, saying it had reinterpreted the Constitution. Most Salvadorans supported the move.

"I don't care if he's violating the Constitution," said Arnulfo Cristostomo Mazariego, who sells pupusas and sodas at a street stand in San Salvador. "If the people decide that they are happy with what he's doing and they want to see more improvement for the country, I don't see a problem. The people are going to decide whether it's unconstitutional. We have the last word."

Mazariego said that for years he had to pay a monthly extortion fee of around $250 to the MS-13 street gang just to be left in peace and operate his business. When Bukele initiated his crackdown, the extortion finally ended. Instead of paying MS-13, he used the money to get a much-needed operation on his eyes, he said.

"There are a lot of people who complain that there is no liberty or human rights under Bukele," Mazariego said. "But I have seen children killed because they didn't want to do a favor for the gangs. Where were human rights then?"

Bukele rose to prominence in 2015 as mayor of San Salvador, the country's capital. The former head of his family's public relations firm, he upended the image of a traditional politician, favoring leather jackets, jeans and backwards baseball caps. He quickly built a communications machine, including secret troll farms to blast critics.

In March 2022, amid a spike in homicides, Bukele imposed a state of emergency that has come to define his presidency. Authorities have sweeping power to arrest anyone they suspect of being a gang member regardless of evidence, hold them indefinitely, and convict them in mass trials of up to 900 people. El Salvador now has the highest incarceration rate in the world, with over 1 percent of its population behind bars.

The results have been staggering. El Salvador registered a nearly 70 percent reduction in murders in 2023, according to government figures. The new homicide rate of 2.4 per every 100,000 people is the second lowest in the Americas after Canada, according to El Salvador's Justice and Security Minister.

"Bukele is basically saying, 'human rights are not compatible with security; democratic values are not compatible to provide actual answers to the people's needs,'" said Ana María Méndez-Dardón, who leads research on Central America at the Washington Institute on Latin America, a D.C.-based think tank.

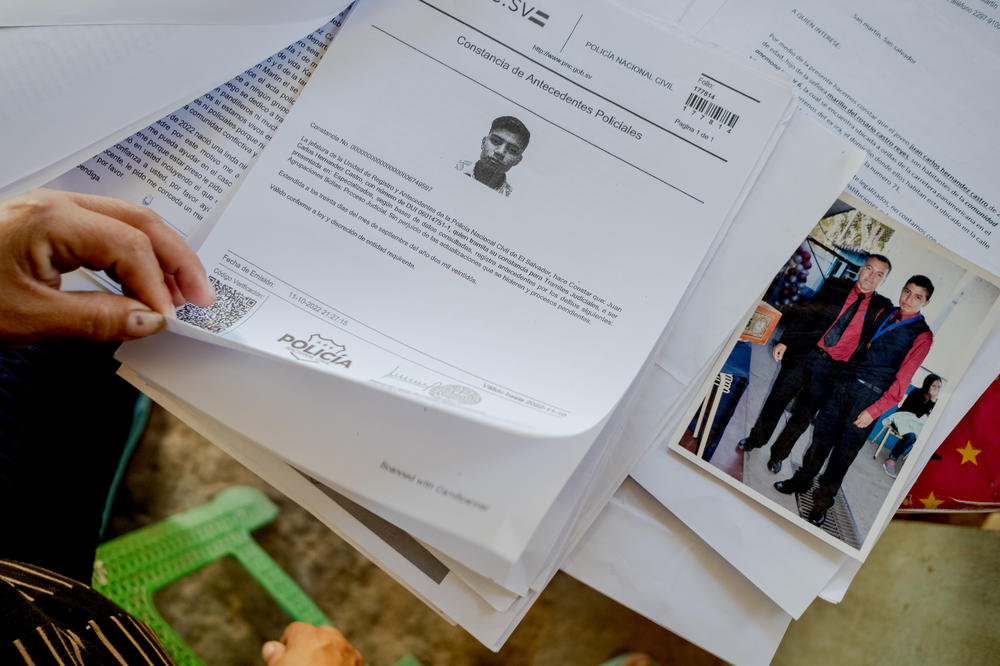

It is people like Jose Antonio Beltran who are buckling under Bukele's state of emergency. At a demonstration outside Congress attended by other families of incarcerated relatives, he tells the tale of his loss.

Police officers arrived at his house one day in December 2022 and asked his 18-year-old daughter to accompany them to the police station. The officers told him they had to arrest a certain number of people a day, regardless of their guilt. They had a "quota" to meet.

"It's been more than 14 months and I don't have any information about what's going on. I am worried because my daughter isn't a criminal. She doesn't have any criminal record. There hasn't even been a trial and they still won't let her go."

Bukele has acknowledged that some innocent people have been unjustly arrested under the state of emergency. But he has ridiculed rights groups who have criticized his policies and accused them of siding with "terrorists," and pushed through a law that would permit the imprisonment of journalists who disseminate messages from gangs.

Bukele's successes have outweighed concerns over human rights. Across Latin America, citizens are calling on their leaders to embrace Bukele's hardline measures. From Chile to Ecuador, many leaders are scrambling to emulate Bukele's security policies. He was even voted Costa Rica's favorite political leader in an October poll there.

Even the Biden administration has toned back its early criticism of Bukele, suggesting that its concerns over his authoritative tendencies will likely take a backseat to the relief that migration from El Salvador is slowing down.

Bukele is on track to gain even more power in the upcoming election. Last year, he signed a law that slashed the Congress's size from 84 lawmakers to 60, a reform critics said was aimed at consolidating power. Some analysts project that Bukele's political party, New Ideas, will win 58 of the 60 congressional seats, giving Bukele unchecked authority.

"The population is consciously headed straight to the butcher," said Malcolm Cartagena, a political analyst in El Salvador who is critical of Bukele. "There will be more imprisonments, more persecution. It is the natural step for a dictatorship."

But democracy is a hard sell in a country where violence and jobs are top of mind. And Bukele's achievements are everywhere to see: Neighborhoods previously controlled by gangs are now patrolled by soldiers. Highways across the country are being rebuilt. Bukele has built a massive library, an animal hospital, and brought the 2023 Miss Universe pageant to the country.

All this is why many Salvadorans like Carlos Flores will vote for Bukele. We meet as he walks round San Salvador's historic district with his three children. They're all wearing T-shirts adorned with Bukele's face. Flores moved to Virginia 25 years ago and was returning home for the first time with his family because it finally felt safe.

"I voted Bukele all the way down the ticket," he said. "Everything is different now. There are still changes to make, but in five years you can't do everything."

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content