Section Branding

Header Content

Oregon pioneered a radical drug policy. Now it's reconsidering.

Primary Content

Oregon voters passed the most liberal drug law in the country in November 2020, decriminalizing possession for small amounts of hard drugs.

Under Ballot Measure 110, instead of arresting drug users, police now give them a citation and point them towards treatment. The law passed with 58% of the vote and also funneled hundreds of millions of dollars in cannabis tax revenue to fund new recovery programs.

But more than three years later, the drug crisis in Oregon – like many other places battling the fentanyl crisis – has gotten worse. And that's prompted a fierce political debate in Oregon about whether Measure 110 has succeeded or failed.

Addressing Measure 110 is one of the priorities for Oregon lawmakers, as they start their new legislative session this week. Democrats, who control the legislature and the governor's office, have indicated they're open to recriminalizing drugs, which could effectively end the most controversial piece of this legislative experiment.

A citation system many say isn't working

On a gray November afternoon in downtown Portland, Officer Joey Yoo stood hunched over a city-issued mountain bike.

The sidewalk was dotted with tiny scraps of tinfoil used for smoking fentanyl. Down the block, a man officers said was high on meth was raging about his stuff being stolen.

"Do you have any questions while I'm talking to you about why I'm giving you this citation?" Yoo asked a young man he stopped for using fentanyl in public. NPR is not using his name because he was in no condition to give us permission to do so.

The man was staring down at the ground, not making eye contact with Yoo. The little he said was hardly audible.

"What brought you out here?" Yoo asked.

"Drugs, I guess," the man replied.

"Do you have any family here?" Yoo asked.

The man didn't appear to respond.

Then, Yoo handed the man several slips of paper. One was a $100 citation. Another had the phone number to a state-funded hotline. If the man were to call and get assessed for addiction, the fine and citation would go away.

"You don't have to go into treatment, but they'll give you information about how to get the treatment," Yoo said. "That's all you have to do."

Court records show the man never made the call.

And that's typical.

So far, police have handed out more than 7,000 citations, but as of December, only a few hundred people had called the hotline to get assessed for a substance use disorder. And even fewer accessed treatment through the citation system.

This exchange – a citation for drug use, instead of an arrest – is a direct result of Measure 110.

Advocates for the measure argued the criminal justice system didn't effectively treat addiction. They also said it disproportionately harmed people of color. Before it passed, the state estimated it would reduce racial disparities in conviction rates.

Back on the street, Officer Yoo said handing out citations doesn't appear to move people from using drugs on the streets into treatment programs.

"The same people I gave a citation to yesterday, today I see doing the same thing," Yoo said.

A heated debate in the state capital

What's happening here on the streets of Portland has led to a passionate debate about substance use and drug policy in Oregon.

Opioid overdoses have surged across the state since Measure 110 passed. In 2019, 280 people died from unintentional opiate overdoses in Oregon. In 2022, that was up to 956 deaths, according to the state health authority – a 241% increase.

A number of researchers have said there isn't evidence that Measure 110 is the cause.

One study published in September by the Journal of the American Medical Association Psychiatry, looked at Oregon and Washington, where drug possession was also decriminalized for several months in 2021. Researchers say they found no evidence between "legal changes that removed or substantially reduced criminal penalties for drug possession in Oregon and Washington and fatal drug overdose rates."

At least one study, however, did find that Measure 110 caused 182 additional overdose deaths in Oregon in 2021. That study, published in the Journal of Health Economics, said those additional deaths represented, "a 23% increase over the number of unintentional drug overdose deaths predicted if Oregon had not decriminalized drugs."

Brandon del Pozo, an assistant professor of medicine at Brown University who studies the overdose crisis and substance use, said that study should be taken with a "grain of salt" because it doesn't control for fentanyl's entry into Oregon's drug supply.

"In virtually every state, fentanyl is intimately linked to overdose," said del Pozo, who also spent 23 years as a police officer, in January during a symposium on Measure 110 in Oregon.

During the past several months in Salem, Oregon's state capital, health experts, law enforcement, and members of the public have offered deeply divided testimony to Oregon lawmakers about what should happen to Measure 110. Hundreds of people submitted testimony, including some who argued that taking away criminal penalties for drug use hadn't worked. Others said they're concerned about safety.

"The police occasionally come in and clean up a specific area with their superficial presence and the drug market moves along to another corner," Lisa Schroeder, who owns Mother's Bistro & Bar in downtown Portland, testified. "The quality of life of our citizenry, from the user to the general population, is suffering."

Cat and Chad Sewell own Sewell Sweets, a bakeshop in Salem. In written testimony, the Sewell's said they've witnessed drug use leading to conflicts outside their business.

"The scenes that we see day in and day out leave us frustrated and questioning just how safe the longevity of our business and livelihood is," they wrote.

Addiction doctors and criminal justice experts in Oregon said that a lot happened between 2020 and now besides Measure 110: not just the fentanyl crisis, but also the pandemic, which taxed the healthcare system, and a growing crisis of homelessness.

Dr. Andy Mendenhall is an addiction medicine physician and the CEO of Central City Concern, a social service organization in Portland that gets a small amount of money from Measure 110. He testified at one of the hearings in Salem, and in an interview after, said it's understandable people are frustrated.

"They're reasonably questioning why this is happening – why it's all not fixed," he told OPB. "Folks are experiencing their own despair, seeing the suffering of others... There's a ton of compassion fatigue."

Mendenhall said people are pointing at Measure 110 and saying it's the reason for Oregon's problems, "when in reality it is our decades-long, underbuilt system of behavioral health, substance use disorders, shelter and affordable housing – that are the primary drivers."

Some treatment providers have testified that if lawmakers recriminalize drugs it will just take Oregon back to a different system that wasn't working.

"Arrest records – it impacts people looking for employment, it impacts their housing, it perpetuates a cycle of poverty," testified Shannon Jones Isadore, CEO of the Oregon Change Clinic, a recovery program that specializes in working with African American and veteran communities in Portland.

"A better solution is to dramatically increase our street services and outreach where there can be adequate care available for everyone," she said.

Amid the debate about how – or even whether to change the law – there's general agreement that whatever should happen next to Measure 110, Oregon made a radical change to its drug laws before the infrastructure was in place to really support it.

Still, treatment has expanded

There are parts of the law that aren't being debated.

The influx of money towards recovery expanded the state's detox capacity, funded new staff such as drug and alcohol counselors, and increased culturally specific treatment programs. Still, a recent study from state health officials found Oregon was years away from being able to treat everyone who needed it.

Joe Bazeghi helps run Recovery Works Northwest, which opened a new 16-bed detox facility during the fall of 2023.

"It's Measure 110 funded," Bazeghi said, during a tour in December. "The purchase, the retrofit, the remodel as well as supplying of this facility was accomplished with support from Measure 110."

The facility opens to a high ceiling with a staircase that goes to a second floor. There's a dining room, game area and off to one side, a living room for recovery group meetings.

The detox center is evidence that Measure 110 is working, Bazeghi said.

"Measure 110 is providing treatment resources that otherwise would not exist," he said. "It's working as well as could ever possibly be expected of a brand new system that had to be built."

Most of the people here are really sick, withdrawing from fentanyl.

A woman named Aleah is one of them. NPR is just identifying her by her first name, because she was still a patient in the detox facility when we spoke with her.

"I feel a lot better than I did yesterday," Aleah said.

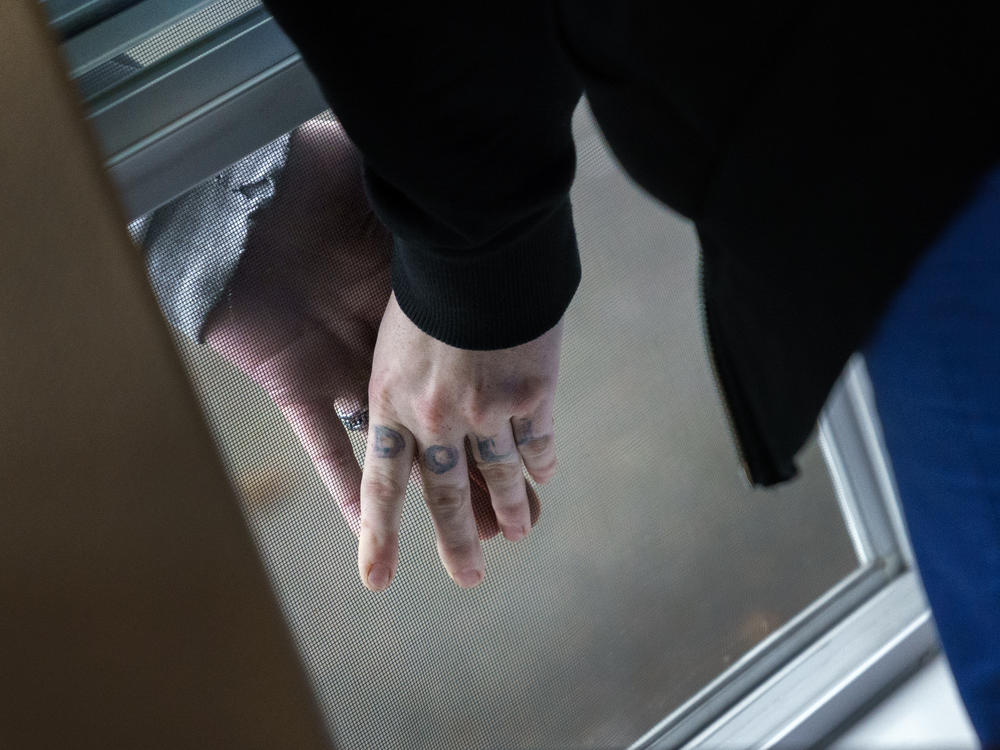

She'd been at the facility for five days. She said she drove 250 miles from Eastern Oregon to Recovery Works because it's where she was able to get a bed. Her boyfriend also wanted her to come here so they could both get sober, she said. While we were talking, her boyfriend, Trey Rubin, who'd just completed residential treatment, walked up and stood outside one of the windows.

"I wish I could come out," Aleah said, pressing her hand against the screen of an open window to meet his hand on the other side.

"At least we can talk through a window," she said. "You look so good."

Rubin recently moved into a sober house in Portland.

"I want to be successful and do things in my life and that's definitely the first step," Rubin said. "You can't really do anything if you're not clean, you know."

He said he's thinking about what he may do now that he's not using drugs.

"I love dirt bikes and writing," he said. "I don't know exactly what I want to do yet. But maybe want to go to school to be an X-ray technician or something like that."

Oregon has faced some criticism for how slow the expansion of treatment programs such as the one that helped Aleah and Rubin has been. But if anything, state lawmakers say they want to invest more in recovery programs, even if they're considering other changes.

Oregon's 2024 legislative session got underway this week, where lawmakers are expected to debate Measure 110's future.

By early March, lawmakers could decide exactly what that future will be. Oregon Senate Majority Leader Kate Lieber – who co-chaired the legislature's addiction committee – told Oregon Public Broadcasting that she's not advocating for Measure 110 to be repealed. But she and other top lawmakers have said they support recriminalizing drug possession so long as there are ways for the criminal justice system to direct people into the treatment programs Measure 110 has helped to expand.

"We knew that we didn't want to go backwards on what was happening with regard to the war on drugs, we can't go back to that – but people are dying of overdoses on the street," Lieber said.

"The state of the drug crisis in Oregon is unacceptable."