Caption

Jefferson Long's rocking chair in Macon's Tubman African American Musuem.

Credit: Grant Blankenship / GPB News

Walk into the main gallery on the first floor of the Tubman African American Museum in Macon, and the first thing you encounter is a very old chair.

“And no, you cannot sit in this chair,” joked the museum’s Ivy Dockery recently. “And don't let me see you rocking back and forth like I see grown folks and kids doing here.”

Because, Dockery said, the chair is important to the exhibit to which it is an entrance — and to history.

“This is ‘Untold Stories: Macon African American History’,” Dockery said.

As it turns out, the untold — or seldom told — story connected to the man who owned the old rocking chair with metal tacked leather is not only a story about a number of firsts for Black history, but also a 153-year-old glimpse into a political struggle we are experiencing today: Who can we call an “insurrectionist” against the federal government? And when should they be allowed to participate, again, in civic life?

Jefferson Long's rocking chair in Macon's Tubman African American Musuem.

The story starts with a year and a place: 1836 in Crawford County, Ga. That’s when and where the man Dockery said owned the old rocking chair, Jefferson Franklin Long, was born.

Later, while Long lived in Macon’s Pleasant Hill Neighborhood, Dockery said he taught himself to read and write.

“From the newspapers that he used to get from the Macon Telegraph office that was right next door to where he used to work,” Dockery said.

He worked as a tailor, but that’s not why Jefferson Long is remembered.

“For him to become Georgia's first African-American congressman is something else,” Dockery said. “It's really amazing.”

Even if most people don’t remember that, said historian Allan Lichtman.

“Most people don't know who he was,” Lichtman said.

Lichtman is a longtime presidential historian and professor at American University in Washington, D.C.

He's also one of 25 distinguished historians from places ranging from Princeton to the University of Georgia who wrote and submitted an amicus brief in the case that originated in Colorado and which the U.S. Supreme Court is now considering called Trump v. Anderson.

In Colorado, the state supreme court affirmed former president Donald Trump can be kept from the ballot under Section 3 of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution because of the actions he took to undermine the 2020 presidential election.

The brief by Lichtman and others and now in the Trump v. Anderson docket is a kind of research paper in which they argue that the 14th Amendment applies to Trump, and if it is agreed a president engaged in insurrection against the federal government, then the amendment applies.

“The 14th Amendment was motivated in part by attempts right after the end of the Civil War of ex-Confederates to take over the new Southern governments,” Lichtman explained.

Section 3 of the amendment should have kept them from office.

Reconstruction, the plan meant in part to extend basic civil rights to African Americans in the South, was being run off the rails.

But, for the first time ever, Congress was composed, in part, of African American representatives, including Jefferson Long of Macon.

Meanwhile, Confederate veterans had already joined domestic terror groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and had killed hundreds by the time Long set foot in the U.S. Capitol.

Six years after the close of the Civil War, in 1871, many in the nation were ready to put the war behind them. Long and the rest of Congress debated an Amnesty Bill designed to act against the section of the 14th Amendment Lichtman says today applies to Trump.

This is where Long made history for a second time as the first Black person to speak as a representative on the floor of the U.S. House.

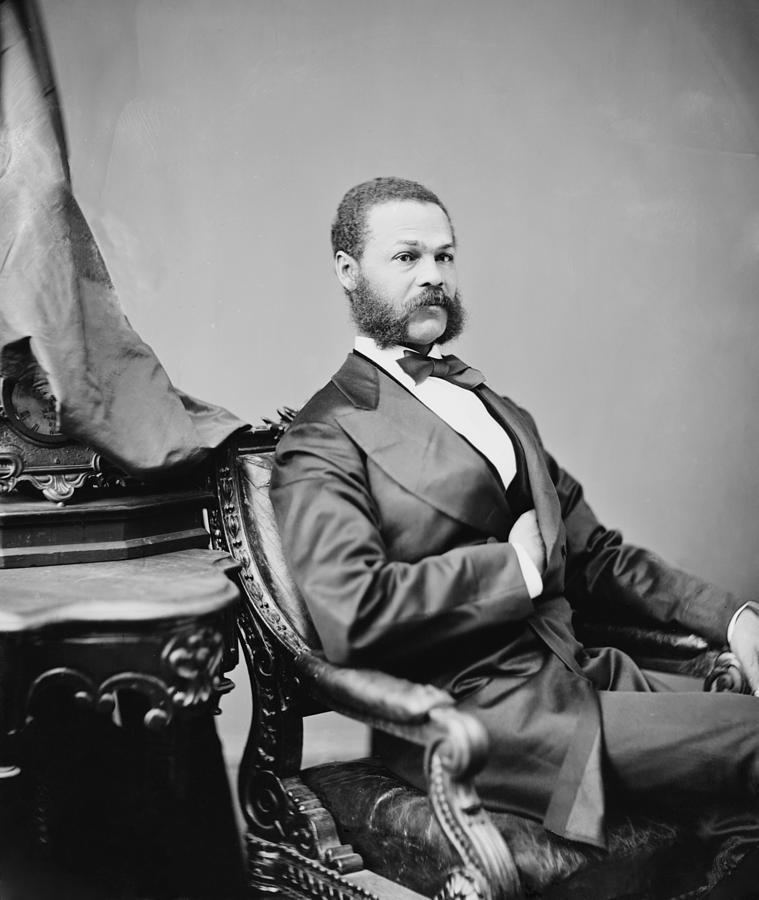

U.S. Rep. Jefferson Franklin Long, who served in Congress 1870-1871.

“So his words were very prophetic and accurate,” said historian Allan Lichtman. “He pointed out that, ‘Why would you want to relieve from disability the very men who have committed these Ku Klux outrages?’”

In other words, Long was asking why would we let these people anywhere near elected office? Especially when, “Those disloyal people still hate this government, when loyal men dare not carry the stars and stripes through our streets.”

Long went on.

“I think that I am doing my duty to my constituents and my duty to my country when I vote against any such proposition.”

Nevertheless, the amnesty bill passed.

“And what happened? The ex-Confederates went back into government, including at least 20 who became governors.” Lichtman said. “And what did they do? They participated in establishing the system of Jim Crow discrimination in the South.”

Allan Lichtman said that in his speech on the House floor, Jefferson Long had some vision of that, too.

“He concluded his statement by saying, ‘I venture to prophesy that you will again have trouble from the very same men who gave you trouble before,’” Lichtman said. “And that was 100% accurate. He was right on the money.”

Disillusioned, Long left office. He would lead Black voters to the polls in Macon in 1872. Some of those voters were shot and killed in the ensuing riot.

The Jim Crow period would become a system of oppression so thorough that it served as a model for Nazi Germany.

Georgia would not send another Black American to the U.S. House for 100 years.

At Macon’s Tubman Museum, Ivy Dockery said there’s a way she sees Jefferson Long’s old rocking chair once the school tours are over and the place is quiet.

“It’s a resting place,” Dockery said.

Jefferson Franklin Long’s final resting place is elsewhere in Macon, in Linwood Cemetery, in the Pleasant Hill Neighborhood he called home.