Section Branding

Header Content

Clownfish might be counting their potential enemies' stripes

Primary Content

At least, that's what a group of researchers thinks.

The Marine Eco-Evo-Devo Unit at Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University has been studying Amphiphrion ocellaris, or clown anemonefish. A study recently published in the journal Experimental Biology from the team suggests that clown anemonefish may be counting the vertical white bars on each other as well as other anemonefish as a way to identify their own species.

But why are they counting bars in the first place?

That answer is wrapped up in fishy marine geopolitics.

Targeted aggression

Clown anemonefish have territorial tendencies.

Unlike the freewheeling, fun-loving protagonist of Finding Nemo, real life clown anemonefish are extremely hostile – even toward human divers. "I have been bitten several times by anemonefish," says Vincent Laudet, one of the study authors. "The female especially controls the territory, and she's very aggressive."

Their colonies are matriarchal and follow a rigid size-based hierarchy: The large colony queen, or alpha female, will lead attacks against anemone intruders. But importantly, she and her disciples are most aggressive toward members of their own species, who could infiltrate the anemonefish colony. She'll even drive out members of her own colony that grow too big and threaten her hard-won throne.

Because of this known behavior, Laudet and his team suspected that the clown anemonefish must have some way of knowing if another fish is a member of its species. They just weren't sure how.

In previous research, they noticed that the fish acted more aggressively toward models with vertical white bars – like themselves – than those with horizontal white bars. Perhaps these fish were looking at white bar patterns to identify the fish who most resembled themselves.

Laudet and other researchers wondered – might they be counting these white bars to know where to direct their wrath?

They may count, but plastic discs elude them

To test this hypothesis, the researchers ran two sets of experiments led by Kina Hayashi, a research fellow and first author on the paper.

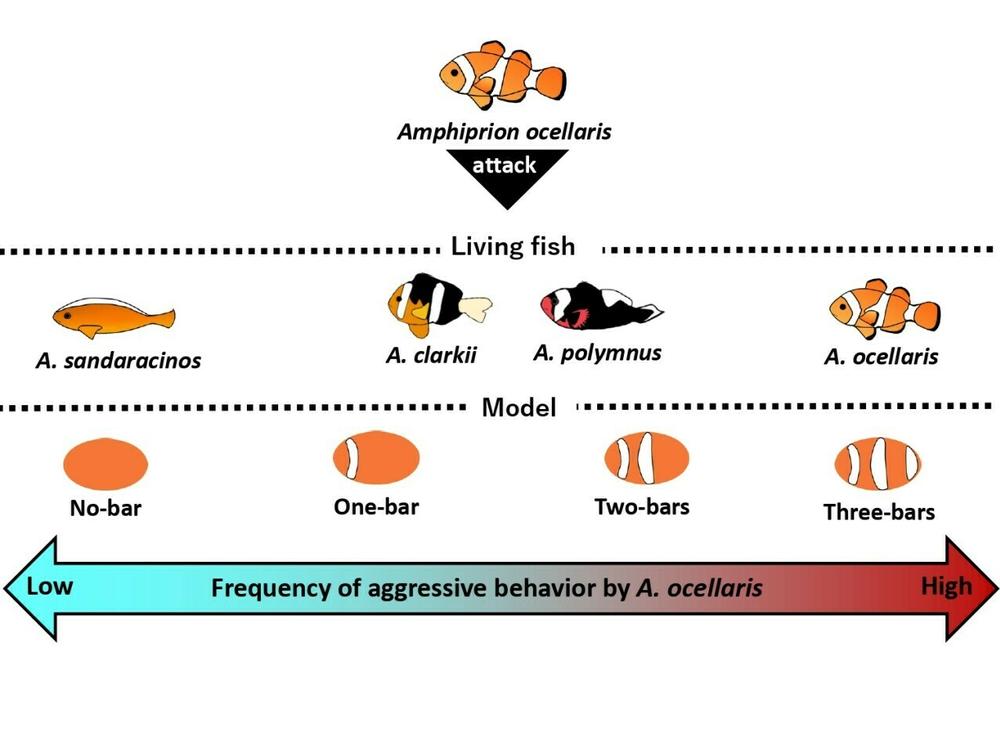

In the first experiment, researchers placed different species of anemonefish with varying numbers of white bars inside small cases within a larger tank. They then observed a colony of immature clown anemonefish to see how long the fish would behave aggressively toward each of the intruder fish. Here, aggressive behavior looks like either charging at or circling a target.

In their second experiment, the scientists painted orange, oval-shaped plastic discs with zero, one, two or three white bars – and again measured those same aggressive behaviors.

The more bars on the fish or the disc, the more they were circled or charged by the juvenile clown anemonefish. "The fish can tell the difference between a dummy with zero, one, two or three bars," says Laudet, "suggesting that they're able to count."

In this community of fish, order above all

The team noticed another revealing bit of social behavior in their experiments: Even though this fish colony lacked an alpha female, the largest juvenile of the bunch led the charge against underwater interlopers. Other experiments have upheld that social positions within a colony are determined by relatively slight differences in size.

In other words, size matters — at least for clown anemonefish.

But not all researchers are convinced of the clown anemonefish' math skills.

When asked for comment, Karen Carleton, a biologist not affiliated with this study, said she was skeptical. "It's difficult to ascribe these behavior differences to the number of stripes," Carleton stated in an email.

Across species of anemonefish there are many different color variations and patterns. Their coloration ranges from deep blacks to vibrant oranges, and their dorsal, ventral and tail fins are colored differently as well. "Any of these different color attributes could be used by the species," added Carleton. "There's much more work needed to know if these fish are using stripes, let alone counting their number."

The team is working on experiments to help confirm the fish' counting abilities.

In any case, Hayashi's and Laudet's experiments are a reminder that even our most beloved aquarium pets and animated movie characters can still surprise and delight us. "People think fish are dumb because fish have no facial expressions that we can read," says Laudet. "But fish are extremely clever. Individuals have their own personalities – and we see that very clearly with anemonefish."

Questions, comments or thoughts on another marine sea creature you want to hear us cover? Email us at shortwave@npr.org and we might feature it on a future episode!

Listen to Short Wave on Spotify, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts.

Listen to every episode of Short Wave sponsor-free and support our work at NPR by signing up for Short Wave+ at plus.npr.org/shortwave.

This episode was produced by Kai McNamee and Rebecca Ramirez. It was edited by Rebecca, Viet Le and Kathryn Fox. Brit Hanson checked the facts. Patrick Murray was the audio engineer.