Section Branding

Header Content

In a pandemic milestone, the NIH ends guidance on COVID treatment

Primary Content

These days, if you're sick with COVID-19 and you're at risk of getting worse, you could take pills like Paxlovid or get an antiviral infusion.

By now, these drugs have a track record of doing pretty well at keeping people with mild to moderate COVID-19 out of the hospital.

The availability of COVID-19 treatments has evolved over the past four years, pushed forward by the rapid accumulation of data and by scientists and doctors who pored over every new piece of information to create evidence-based guidance on how to best care for COVID-19 patients.

One very influential set of guidelines — viewed more than 50 million times and used by doctors around the world — is the COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

"I think everyone [reading this] will remember [spring of] 2020, when we did not know how to treat COVID and around the country, people were trying different things," recalls Dr. Rajesh Gandhi, an infectious diseases specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital and a member of the NIH's COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Around that time, people were popping tablets of hydroxychloroquine and buying livestock stores out of ivermectin, when there was no proof that either of these drugs worked against infection by the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 (later studies showed that they are ineffective).

It was early in the COVID-19 pandemic when the NIH convened a panel of more than 40 experts and put out its first guidelines, which became a reference for doctors around the world.

For the next few years, it was an "all hands on deck" endeavor, says Dr. Cliff Lane, director of the clinical research division at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and a co-chair of the panel.

Panel members met several times a week to review the latest scientific literature and debate data in preprints. They updated their official guidance frequently, sometimes two or three times a month.

End of an era

Lately, the development of new COVID-19 treatments has slowed to a drip, prompting the guideline group to rethink its efforts. "I don't know that there was a perfect moment [to end it], but ... the frequency of calls that we needed to have began to decrease, and then on occasion we would be canceling one of our regularly scheduled calls," says Lane. "It's probably six months ago we started talking about — What will be the end? How do we end it in a way that we don't create a void?"

The last version of the NIH's COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines was issued in February. The archives of the guidance — available online until August — document how scientific understanding and technological progress evolved during the pandemic.

Lane says specialty doctors groups — such as the American College of Physicians and the Infectious Diseases Society of America — will be the keepers of COVID-19 treatment guidance from now on. They're the usual stewards of best-practice guidelines anyway, he says.

At this transition point, panel members say the evolution of COVID-19 treatments offers lessons for dealing with new emerging infectious diseases.

Turning points in treatment

In the spring of 2020, hospitals in parts of the U.S. were filling up with the first pandemic wave of COVID-19 patients. "We were just learning how the disease progressed. Our first guideline [issued that April] was, basically, we don't know what does and doesn't work," says Gandhi, of Massachusetts General Hospital. "But we did learn fairly quickly — mostly in hospitalized patients — what did work."

By June 2020, data supported a treatment plan for very ill patients: Use steroids like dexamethasone to stop the body's immune system from attacking itself, and combine them with antivirals, to stop the virus from replicating.

Then, about a year into the pandemic, came another turning point: solid evidence that early treatment with lab-made antibodies could help keep COVID-19 patients out of the hospital. "This was a somewhat unexpected and dramatic [positive] effect," Lane says, noting that previous attempts to develop antibody therapies against influenza were unsuccessful.

The way these drugs, called monoclonal antibodies, worked out "provided so much insight into the virus itself," says Dr. Phyllis Tien, of the University of California, San Francisco, and a member of the COVID-19 treatment panel. While initially successful, the antibodies targeted the coronavirus's fast-changing spike protein. New strains of the coronavirus would knock out each new antibody version in about a year.

This cat-and-mouse strategy didn't last.

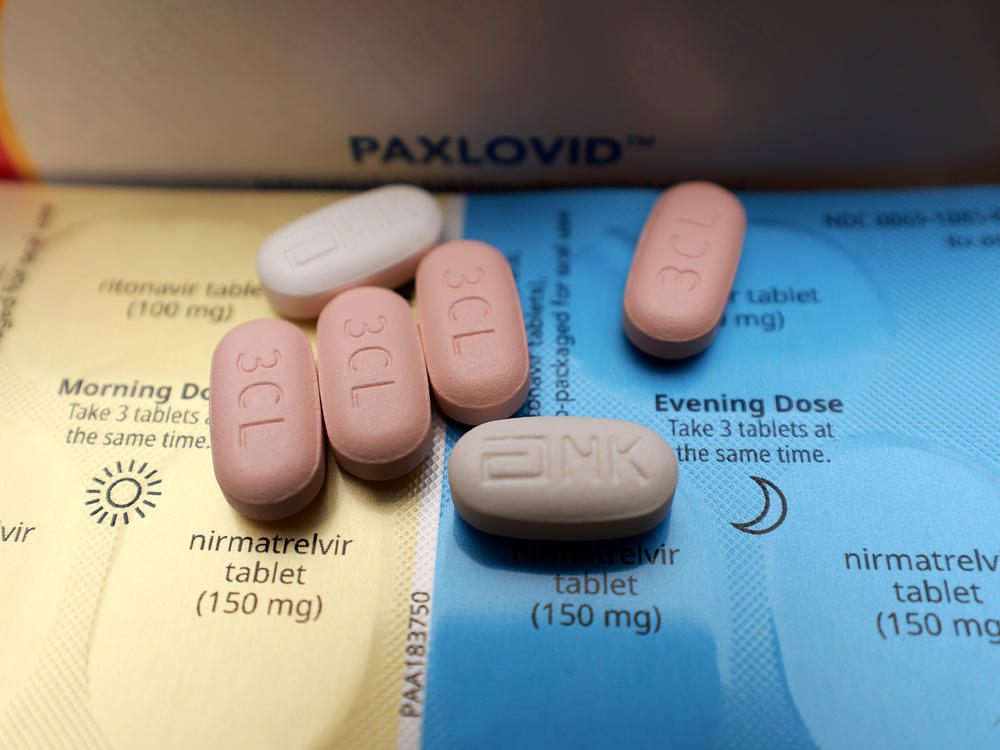

By the end of 2021, the Food and Drug Administration authorized two pill courses that COVID-19 patients could try taking at home to get better: Merck's molnupiravir and Pfizer's Paxlovid, a combination of two antiviral drugs: ritonavir and nirmatrelvir.

"Both have, as I like to say, warts," says Carl Dieffenbach, director of the AIDS division at NIAID and part of the agency's program to develop antivirals for pandemics. "Molnupiravir's warts are that it works marginally," meaning the data shows that it isn't very effective. And while Paxlovid works pretty well, it can't be taken with a lot of common drugs. "[Many] doctors are uncomfortable or unwilling to manage ... [patients] who should take it, but are on a statin or some other drug through the process," Dieffenbach says.

Another antiviral drug, remdesivir, is also considered fairly effective for treating mild to moderate COVID-19, though it's harder for patients to access, as it's administered intravenously. The drug company Gilead tried to make it into a pill, but it didn't work.

Underuse of effective treatment

The hurdles that come with each of these outpatient treatments have contributed to low usage rates among the patients they're intended to help, says Jenny Shen, a research scientist at the CUNY Institute for Implementation Science in Population Health.

Shen's research found that at the height of the pandemic, just 2% of COVID-19 patients reported getting molnupiravir and 15% reported getting Paxlovid, among those considered to be eligible for the drugs.

The study uses data from 2021-2022 — a time when the federal government bought these drugs from manufacturers and provided them free to states, health centers and pharmacies. Shen notes that rates of use have likely further declined since late 2023, after the drugs got transitioned to the commercial market, since they're "not as free as before" and, in many cases, require copayments.

Another part of the problem is that doctors can be reluctant to prescribe these outpatient treatments, since they can be difficult to manage if a patient has other health problems, Shen says.

Yet another challenge is that many patients with risk factors just don't believe they'll get very sick. "A dilemma we have observed is that patients want to see how severe their disease may become," but in waiting, they become ill beyond the point where the treatment would help, Shen says.

Even now, when some 13,000 people are getting hospitalized with COVID-19 each week, more patient education on how the drugs work and when they're most effective could help those who are sick make better-informed decisions, she says.

There's one more COVID-19 drug in late-stage clinical trials that could be promising, says Dieffenbach. It's a pill course by the Japanese company Shionogi that's getting tested for its efficacy against both acute and long COVID. "I'm waiting to see how this all turns out," he says, "But then that's it. That's what's in the pipeline" for the near future.