Section Branding

Header Content

In Macon, the city’s cherry blossom festival chases the calendar amid a changing climate

Primary Content

Passing clouds shifted the afternoon light from gold to gray to gold again as Meena Chandrasekar tried to photograph her daughter Anitra framed by cherry blossoms.

The cherry trees surrounding them on the side of Macon’s Ingleside Avenue were in full bloom March 21, the last Thursday of this year’s International Cherry Blossom Festival.

After lots of different angles, Chandrasekar was satisfied she’d captured a little of what she sought when she and her two children came to Macon from Jacksonville — trees full of flowers shaded from near white to light pink, only lasting for days.

She said she thought about making the trek to the famous scene in Washington, D.C., but then thought about how far away that was. Then she learned about Macon’s claim to more trees than Washington and came to Georgia instead.

“It’s been good!” she said.

What she may not have known is that by the time she made her photo, those blossoms likely had only hours left. The next day forecast called for rain almost certain to knock the blooms to the ground. And if she'd tried to make the same trip 60 years ago on the same day, it’s likely she would have been far too early to see flowers blooming at all.

The spot Chandrasekar chose to make her photos is owned by Macon’s Fickling family. The path to Macon’s claim as host to some 350,000 Yoshino cherry trees started here.

“The very first festival was really an award ceremony where Grandpa was given the award for all of the trees that he donated to the city of Macon,” said William Fickling III.

Fickling’s elder namesake had become enamored with the trees years before. Fickling said when Macon’s Third Street Park was packed with people for the award ceremony, another local legend, Carolyn Crayton, asked: Why not do the same thing every year?

And so a festival was born. The festival, of course, would need to be planned every year around the marquee event, the peak period for cherry blossoms.

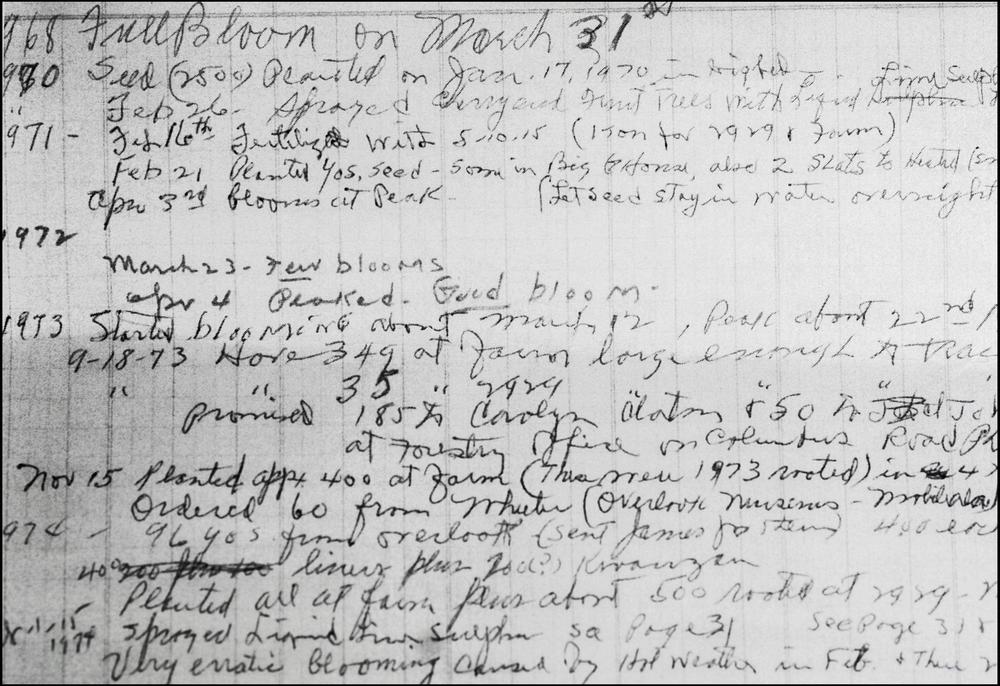

“My grandfather has been tracking that since 1968; we have his journal,” Fickling said.

The journal is where the elder Fickling started what would turn out to be an almost 60-year-long data project. In the first entry from 1968 he recorded that full bloom fell on March 31, some eight days later than this year.

“And now my daughter Laurie has the journal, and so she's keeping it all in Google docs because she's young and smart about those kinds of things,” Fickling said.

And Fickling has been able to look at the full picture of peak blossom data and not just a couple years at a time.

“So I recently calculated the average,” he said. “His average was March 23rd — which happens to be his birthday, which is also when we typically celebrate Founder's Day.”

That date of March 23, Founder’s Day, is a hard point for festival planners. It has to fall within the two-week schedule.

But in the data he sees a problem.

“The average peak bloom date is moving,” Fickling said. “When I calculated it a couple years ago, it had moved to March the 22nd.”

A day sooner than in his grandfather’s day.

“Now, that doesn't sound like a lot, but as we know, a 1-degree centigrade hotter Earth is really bad news, and the cherry trees are seeing that,” he said. “Next year it'll probably be about the 21st.”

“It's making us push the festival earlier.”

Planners have moved the Cherry Blossom Festival kickoff earlier, scooting it up by a day every year for years. But with the requirement to still take in Founder’s Day — March 23 — that can only last so long. Fickling said he and the rest of the festival’s planners are looking for new trees.

Because cherry trees also need enough time in the winter cold to flower at all, Washington, D.C., is also in a fight to keep its Yoshino cherry trees. There, at the National Arboretum, a more heat-tolerant variety called the Helen Taft is in development.

Fickling said those trees may be planted in Macon one day. They, or some other tree like them, may even be planted in the place where the whole cherry tree obsession began.

“We've been in contact through the Japanese embassy in Atlanta with the horticulturists in Japan, and they're working on the same problem,” Fickling said.

The problem of preserving the ephemeral beauty of the cherry tree in a rapidly warming world.