Section Branding

Header Content

'Women Behind the Wheel' explains how cars became a gendered technology

Primary Content

Believe it or not, there was once a prototype of a minivan that included a small washer and dryer — that way, moms could do the laundry while the kids were at soccer. That vehicle, explains journalist Nancy Nichols, was never produced, but it's an eye-opening window into the long relationship between car manufacturers and their female consumers.

Nichols has written a new book on the history of women and car culture. In Women Behind the Wheel: An Unexpected and Personal History of the Car she explains how cars became a gendered technology.

Cars have always been major characters in Nichols' life. Her father — who lost his brother to an auto accident as a child — became a car salesman, mostly selling used cars. Her brother drove race cars on weekends. Decades later, Nichols' father was in a car crash that resulted in a traumatic brain injury that changed his life.

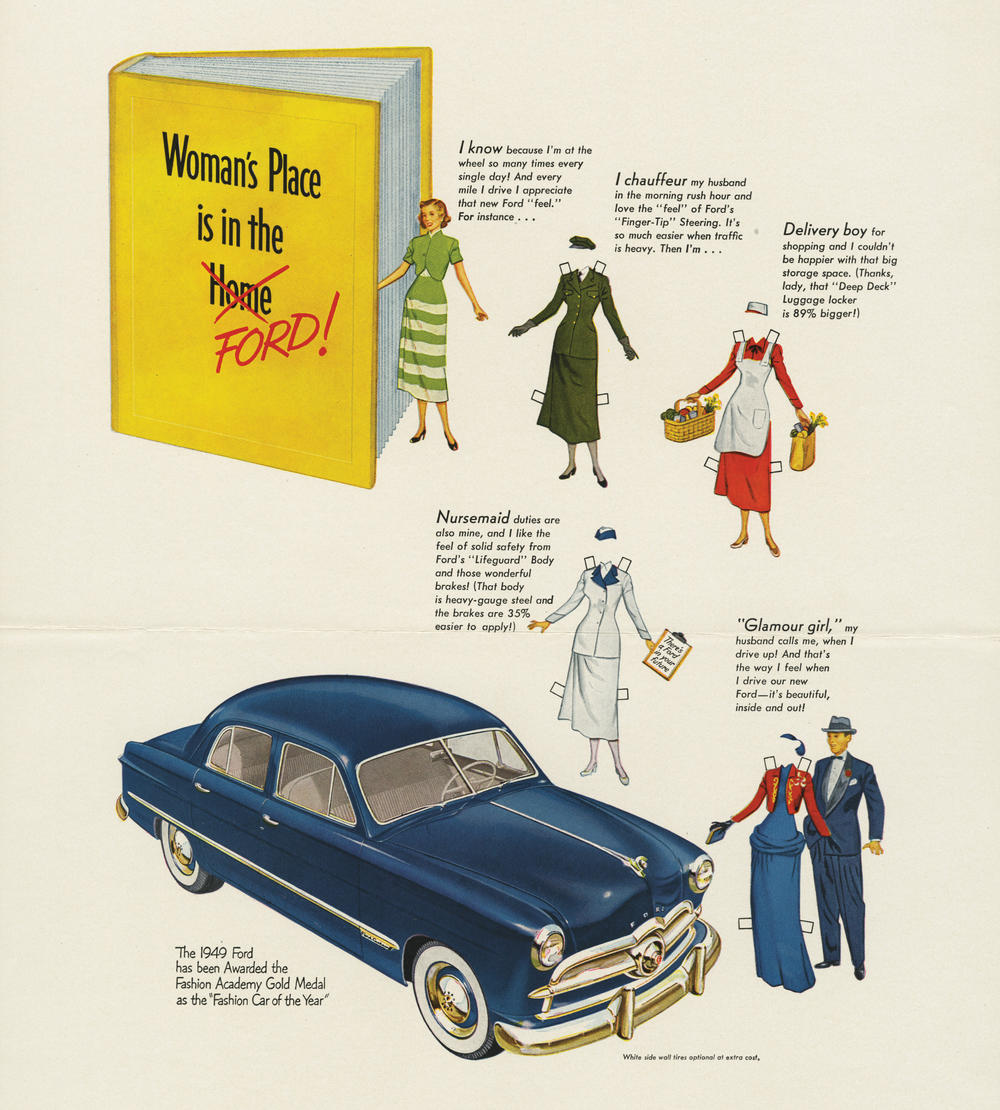

"The car, for men, has always been about adventure, about power, about strength, about a performance of their own masculinity. ..." Nichols says. "The car for women was about making sure that you could take care of your domestic duties — what you needed to get done for your job as a mother or your job as a housewife."

Interview highlights

On how the invention of the electric starter made cars accessible to women

The early cars were hand-cranked, and that was part of why they were very difficult for women to drive. They were very hard to start. Also, they didn't have power steering. They didn't have power brakes. There were some models in which it was very difficult for women to even reach the pedals. ...

It wasn't until 1910 when a man named Charles Kettering developed an electric starter for the car, and this was a real game changer for women because it allowed women to start the car without a great deal of personal strength, and it greatly expanded their ability to use the car when there weren't men around.

In the first instance, the ladies car was an electric car. It was meant for women who were largely very wealthy. For example, Clara Ford drove a Detroit Electric. She did not drive a Ford. That's because in the early days, these combustion engines were thought too difficult for women to start and drive, and also too dangerous. There was also some concern that the combustion engine would create unwanted sexual excitement for women. They vibrated ... so they were not allowed to have them. Wealthy women, by and large, had the electric. They were kind of like golf carts today. They drove them around their estate. They drove them to their friends, for social engagements.

On car coats and automobile fashion in the 1910s

The car coat was designed to help women get in and out of the car. ... I went to the New York Public Library, and I found from Saks Fifth Avenue, a catalog, it was about 200 pages long, and it was all about helping women adapt to this new car culture, which was really very new. So early cars were open. They didn't have roofs. Women got dirty. They were cold. Women were sold ermine blankets. They wore goggles that evolved as the car became more enclosed.

And so women ... were advised by the Ladies Home Journal, for example, to wear gloves, to have a hat with a short veil, because the act of driving a car is performative, and it's always been expected that women dress a certain way and look a certain way. So, for example, Ford had coats that were made to match, used the same material in the interior of the car to create matching handbags, matching coats. So it was a very coordinated thing.

On how car manufacturers coached salesmen on how to sell cars to women

For example, certain salesmen were told to go to the home, find out what the woman's favorite color was, then bring a car that was in that shade to the home — a very decked out car that she might feel attracted to. ...

The interior of the car was thought to be particularly a female space, a place for domestic arts. So this is a place where women were involved in picking the fabric of the seats or the floor mats, the interior colors. So the slogan or kind of the watchword from that time would have been, "He picks the engine. She picks the paint job."

On the minivan's reinvention — from hippie car to mom car

The hippies use the van as a kind of roving space for romance. So they would have on their vans, "if it's a rockin', don't come a knockin'." Because these were intimate spaces that were designed for intimacy. They had specific mood lighting. They had wine racks, they had shag rugs. ....

Fast forward a little bit to my generation, I'm a Boomer. I have always worked. I had a young son when I was working, so I use my minivan. I drove a Honda Odyssey, and I used it to meet my dual responsibilities as a mother and as a professional woman, and I'm about 65 years old. ... My generation was the biggest waves of women who are trying to meet these dual responsibilities. So we would have on our suit and our little high heels and our cute little bow ties, and we would also be in the grocery store, and we would be dragging kids through the grocery store in those outfits, and we would be taking them to soccer.

You have to give the American automobile industry so much credit: They were on every single demographic trend. They fully understood what women wanted and needed, and they were out to make it work for women, in very capitalist ways. They weren't doing it out of generosity, but they did a great job. And the minivan was really created in order to help women make that transition from home to work to getting the kids to soccer. ...

I think when most of us were fantasizing about what it meant to be a woman, we weren't thinking, "Oh, we're going to be raising our child at 45 miles an hour." But we spent a lot of time in those minivans.

On how Subaru became seen as a car for lesbians

Around 1994, a set of executives at Subaru were having focus groups in western Massachusetts, and what they realized [was] ... the people who were buying their cars fell into two categories: One was what we would call kind of an essential worker now. They were nurses. They were EMTs. They had to get out in all weather. There was no chance that they could skip work if the weather was bad. And the other group tended to be lesbians. And they found this very interesting, and they pursued it. And what they realized is that lesbians were very fond of their car.

So they started speaking and trying to encourage more lesbians to buy their car, by a kind of coded set of advertisements. So in the advertisement, the license plate, for example, would say, "get out and stay out." Which was coded language. It could mean get out into nature and stay out in nature, but it could also mean, you know, come out of the closet and stay out of the closet. Or the license plate would say "P-Town" and Provincetown in Massachusetts has always been a very welcoming place for the gay community. So they started and became the first company to actually get out front and market to the gay community.

On "male" crash dummies as an industry standard

The original crash dummy was a six-foot man with a hat on. And came from dummies that were created to test for pilots to eject out of their planes. So those crash dummies were modified and began to be used in the manufacturing of automobiles. So there's two ways in which these dummies are used. And one is the federal government has their standards, their crash standards, and they have their dummies. And those dummies historically have been made for men, and they don't take into account smaller women.

To their great credit, automobile manufacturers now test their vehicles using many different kinds of dummies, but the actual ratings they get come from these dummies that are used by the federal government. And there has been a push by women legislators to try to get that changed. And there's been some movement, but it's still quite concerning. And as a result of that, women are more likely to be injured in a crash because their musculature is different.

On where women fit into the car technology of the future

We're at this really important point in the life of the automobile where we're going to have autonomous vehicles, we're having electric vehicles, we have women legislators who are arguing for better, more inclusive kinds of safety dummies. So I want women to be aware of all these aspects of the car. The car as a domestic space, the car is a place where you can really be injured. And I want them to just kind of take ownership of this. We are active consumers in the automobile world.

Lauren Krenzel and Susan Nyakundi produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey adapted it for the web.

Bottom Content