Section Branding

Header Content

Ancient predatory worms have scientists rethinking the history of life on Earth

Primary Content

500 million years ago, the world was a very different place. Basically all life lived in the water, which held a lot of animals that looked pretty different from the ones we recognize today.

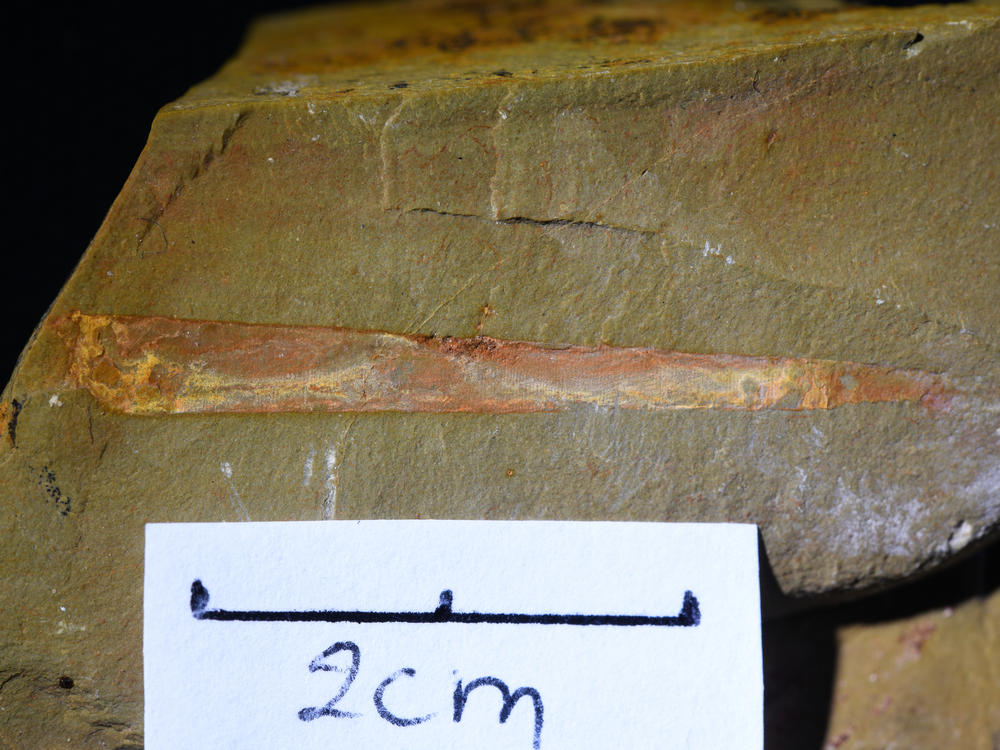

One of these was a group of predatory worms with throats covered in spines, hooks and teeth to trap their prey. They built tubes around themselves and lived inside of them, waiting for their next victim to crawl by.

"These worms are pretty small ... But if you're an invertebrate crawling along the sea floor, this thing is like a nightmare — just like predatory features all being pushed out of its throat at you," says Karma Nanglu, a postdoctoral fellow at The Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University.

Scientists have known for a while that these approximately inch-long terrors lived during the Cambrian period, roughly 500 million years ago. But the end of the Cambrian period was marked by a mass extinction, so Nanglu and other researchers researchers thought that these Selkirkia worms had been left behind like much of the other marine life at the time.

"The animals that came out of the Cambrian Explosion ... were like life's big first, like Big Bang in some ways," Nanglu says. "And then afterwards they didn't really persist all that long."

But a paper recently published in the journal Biology Letters by Nanglu and paleobiologist Javier Ortega-Hernández showed examples of a new species of this Selkirkia worm in the fossil record 25 million years after researchers thought they'd vanished from the Earth. Nanglu says this finding may change how scientists understand life in different periods of Earth's ancient history.

"From the biological perspective, maybe some of these boundaries are a little bit more fuzzy than we previously thought," he says.

Curious about other weird wonders of the ancient Earth? Email us at shortwave@npr.org.

Listen to Short Wave on Spotify, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts.

Listen to every episode of Short Wave sponsor-free and support our work at NPR by signing up for Short Wave+ at plus.npr.org/shortwave.

Today's episode was produced and fact-checked by Rachel Carlson. It was edited by Rebecca Ramirez. Ko Takasugi-Czernowin was the audio engineer.