Section Branding

Header Content

How do you build without over polluting? That's the challenge of new Catan board game

Primary Content

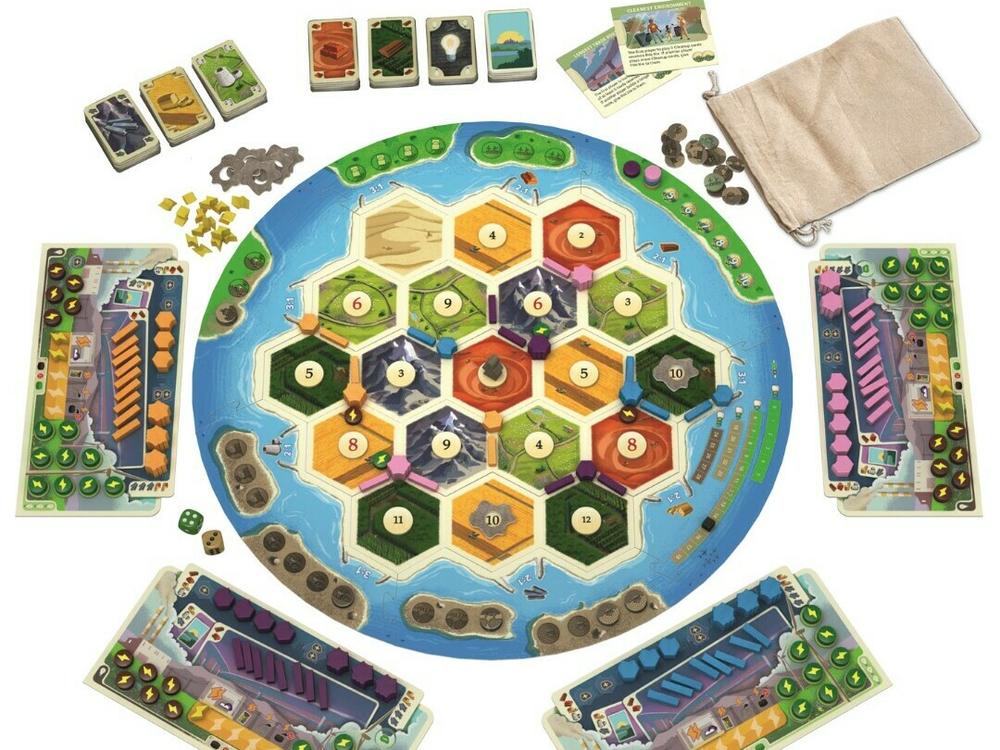

In the original version of the popular board game Settlers of Catan, players start on an undeveloped island and are encouraged to "fulfill your manifest destiny." To win you have to collect resources and develop, claiming land by building settlements, cities, and roads.

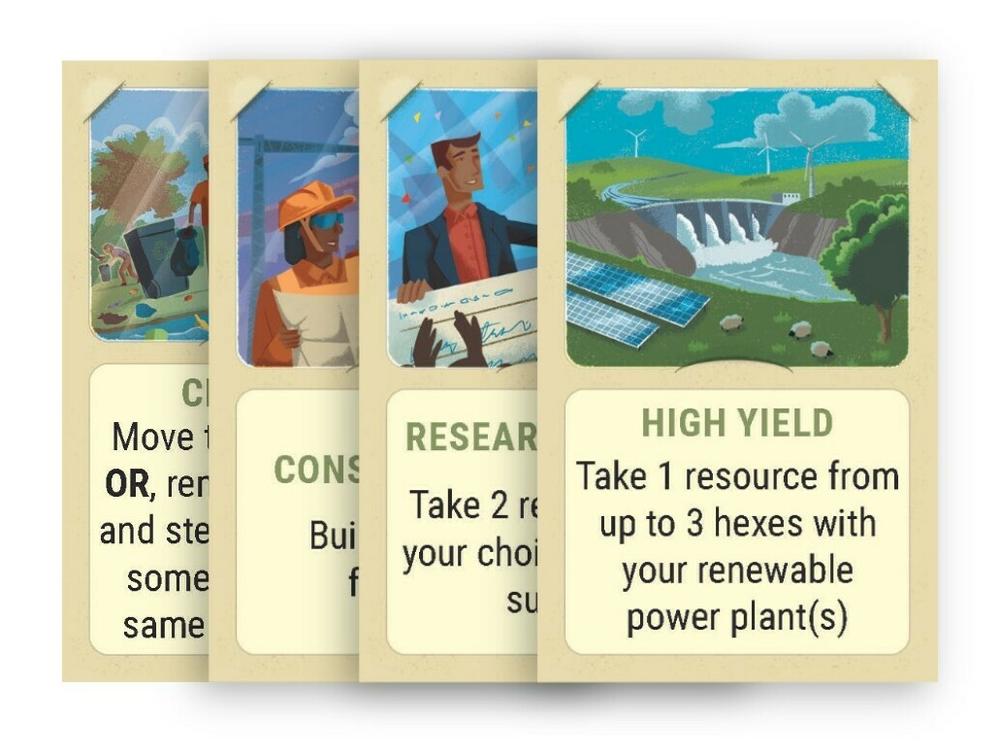

A new version of the board game, Catan: New Energies, introduces a 21st-century twist — pollution. Expand responsibly or lose. In the new version, modern Catan needs energy. To get that energy players have to build power plants, and those plants can run on renewable energy or fossil fuels. Power plants operated on fossil fuels allow you to build faster but also create more pollution. Too much pollution causes catastrophes.

"Generally it's tough to depict reality in a game. The reality is always so much more complex," said Benjamin Teuber, managing director of Catan's production company and co-developer of the new game. Games, he adds, need to be fun.

The newest iteration of Catan will hit shelves this summer. And it aims to mirror reality in a couple of clear ways: Energy from fossil fuels creates more planet-altering pollution than renewables; too much pollution leads to bad things; those bad things are felt unequally.

"Sometimes flooding hits everybody, just as we see [in the real world]," said Teuber. "It doesn't matter who created the pollution. It affects everyone."

Teuber, who co-developed New Energies with his late dad, Klaus Teuber, said the game was an old idea they dusted off during the Covid-19 pandemic. It's one that's become increasingly relevant as the real world grapples with the effects of real pollution: a rapidly warming planet that's worsening wildfires, floods, and heatwaves.

The game's developers are aware of the relevancy. "It's a very interesting topic in every culture that we publish in," Teuber said.

Polls show climate change is viewed as a major concern across many parts of the world. But adapting to the changes and addressing its roots have proven difficult. Teuber said he thinks board games can help move the conversation forward. Board games generally require people to sit around a shared table, to read each other, to negotiate and take risks, "without having a severe and bad consequence," he said. "Unless divorce is the result."

Climate change experienced through board games

Catan: New Energies is not the only new board game centered on climate change. Daybreak, the latest game from the creator of Pandemic, a popular cooperative board game, tasks players with working together to cut carbon emissions and limit global warming.

In a blog post on Daybreak's website, the game's co-designer Matteo Menapace wrote that he and co-creator Matt Leacock were inspired to make the game because they were both worried about climate change and weren't sure what to do about it.

"The problem with the question 'what can I do about climate change,' is how it implies climate action is like a single-player game, with you alone fighting against this huge invisible enemy," Menapace wrote. They believe addressing climate change and its causes will require a collective effort. That's why Daybreak requires "total cooperation," Menapace wrote. "It's a big leap from the current state of climate (in)action, but not an unreasonable one... and we aim for this game to play a role in accelerating this shift."

Catan Studio, the developer and publisher of Catan games, isn't as explicit in its intentions with its new game. The phrase "climate change" doesn't show up in any of the Catan: New Energies' promotional materials, packaging, or rulebooks. "Pollution" is the catch-all term for the problem.

Teuber said they talked about adding the term but decided to focus on energy and presenting players with the option of fossil fuels or renewable. "We assume players will draw their own conclusions as they engage with the game," he said.

The game's studio does note in its press materials that according to "evidence-based research and expert sources, [the] new game elements will get players thinking and talking about important issues."

A 2019 review of published research on board games and behavior by a team of Japanese researchers showed that "as a tool, board games can be expected to improve the understanding of knowledge, enhance interpersonal interactions among participants, and increase the motivation of participants." Though, it noted, the number of published studies on the topic is limited.

Dialogue from gameplay

"What games are really powerful at is starting dialogues," said Sam Illingworth, an associate professor of science communication at Edinburgh Napier University in the UK.

In the gaming world, there's a concept called the Magic Circle — a theory attributed to Johann Huizinga, a Dutch cultural historian, who in the 1930's posited that play creates a separate world with separate rules.

"It's the idea that we suspend disbelief on the gaming table," Illingworth said. "Like in the game Monopoly, it's perfectly good – strictly advisable – for me to want to bankrupt you, which is behavior that's morally repugnant away from the gaming table, but it means that those social hierarchies can break down and we can have conversations that we wouldn't normally be able to have."

In 2019, Illingworth co-designed a playable expansion to the original Catan that added climate change and sustainability to the gameplay. They called it Catan: Global Warming and posted the rules and instructions on how to adapt a regular Catan game online.

In the add-on, if players add too many greenhouse gasses, the whole island is destroyed and nobody wins. "So that creates a game state where psychologically there's obvious causality between actions and what happens, right?" Illingworth said. "So rather than just having a conversation about what might happen, you're actually experiencing it."

In Catan: New Energies, if pollution reaches too high a level to continue, the win goes to the person who built the most renewable energy power plants.

While workshopping the new game with colleagues, Teuber said they would often play too aggressively, aiming to "grow, grow, grow," they would build out fossil fuel power plants, he said. "We always manage to over pollute."

Test groups did the same. But after those games, the players would often come back and say, "We had heavy discussions afterwards," Teuber said. "We all felt kind of bad, we learned and thing or two, and the next game we played differently."