Section Branding

Header Content

Freedom Monument Park tells honest story of enslaved people

Primary Content

Bryan Stevenson, executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, says in the United States the story of enslaved people is not told with real honesty. That's part of the reason he and EJI created and opened the 17-acre Freedom Monument Sculpture Park in Montgomery, Alabama.

The new park is a direct confrontation with slavery and its impact on this country and is EJI's third public space, which includes The Legacy Museum and a memorial for victims of lynching. A walk through the new park is designed to get visitors closer to the experiences of enslaved people in America.

The park is bounded by two monolithic forces that made the slave trade in the United States possible. The Alabama river, which brought over 10,000 Africans captured and trafficked into the state's slave trade, and the railroad.

Stevenson gestures to railcars rolling by the visitor center at the park. "These rail cars that you're hearing, they're on rail tracks that were built by enslaved people because of rail trafficking," Stevenson said. "Montgomery had one of the largest populations of enslaved people in the American South."

Stevenson and the Equal Justice Initiative represent people they say are unfairly convicted in the criminal justice system. They've also created exhibits to educate people about inequities in the system, and now with this park they've opened a dialogue about the history of enslavement in the United States.

Stevenson says museums that address slavery are usually found in old plantation homes that are really about glorifying or romanticizing those who enslaved others.

"We wanted to create a space where the lives of enslaved people could be centered with their perspective, their experiences would direct the narrative and shape the experience," Stevenson explains.

On the first section of the path is a large installation by Ghanian artist Kwama Akoto-Bamfo titled, "We am very cold".

Nine metal figures appear to shiver and brace against the cold, some in chains, one wearing a heavy, spiked punishment collar. Akoto-Bamfo says he uses life-size figures like this to directly address the viewer and to get them thinking.

"We see young Africans, teenagers arrive in a strange world, a strange new world," Akoto-Bamfo explains. "I want you to size them, I want you to see, am I taller than this person? Am I shorter than this person? How can I relate to this person?"

The artist uses visual cues to connect the statues. One woman has a scar on her face. Later, her figure appears again in the park, this time picking cotton in a field.

Another narrative that's told on the path is on various plaques in written form. It's the words of William Wells Brown. He was a historian and novelist, and he was enslaved in the early 19th century along with his mother in Kentucky.

Brown, who worked in the house, writes about waking one morning to hear his mother, who worked in the field, being beaten.

Brown writes in his autobiography, "I heard her voice, and knew it, and jumped out of my bunk, and went to the door. Though the field was some distance from the house, I could hear every crack of the whip, and every groan and cry of my poor mother."

This almost visually graphic ability to write about his experience with enslavement is something historian Ezra Greenspan was drawn to.

"It's one of the broadest perspectives we have on the history of slavery from someone who was writing from within the experience," said Greenspan, who has written a biography of Brown.

The hardship of slavery is also portrayed in the park through other sculptures. There's one of leg chains in the corner of a railroad car, another is a statue of a young boy forced to drag a cotton bag larger than himself through a field.

There are also representations of faith and spirituality. One sculpture is of stacked tambourines painted white, ready to be played at a wedding or in church. The word "love" also appears in prominent places across the park.

This is a deliberate choice by Stevenson.

"I am, more than anything, amazed by the capacity of enslaved people to love in the midst of sorrow, to find something redemptive, to find something genuine and pure and beautiful when you're surrounded by so much ugliness and pain and violence," he said.

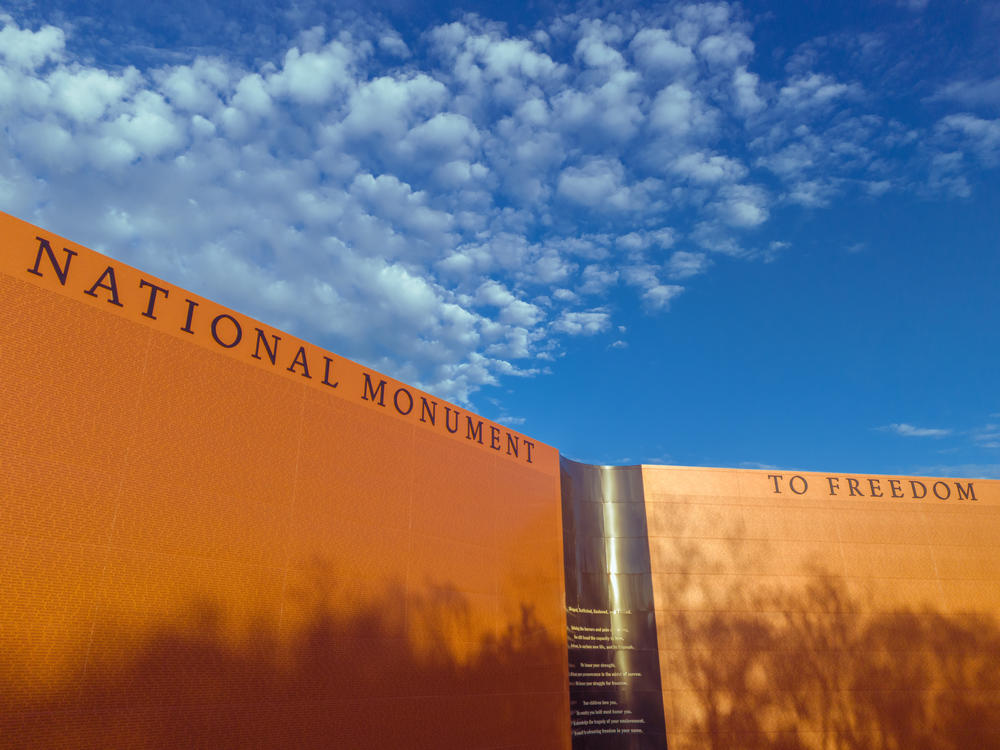

Near the end of the path sits a fifty-foot-high golden wall. It's the Monument to Freedom that includes 100 thousand last names. Those last names represent 4.7 million enslaved people set free after emancipation.

Stevenson says behind them are the struggles and commitments and sacrifices of another 6 million who never saw freedom.

"It's a way of just humanizing this community of people who endured so much, who suffered so much and yet gave so much to this country," he said. "This nation wouldn't be what it is without the labor and the sacrifice and the toil and the struggle of enslaved people."

With this new monument park, there's now a physical reminder of the impact slavery had on this country and on the people who lived it.

Bottom Content